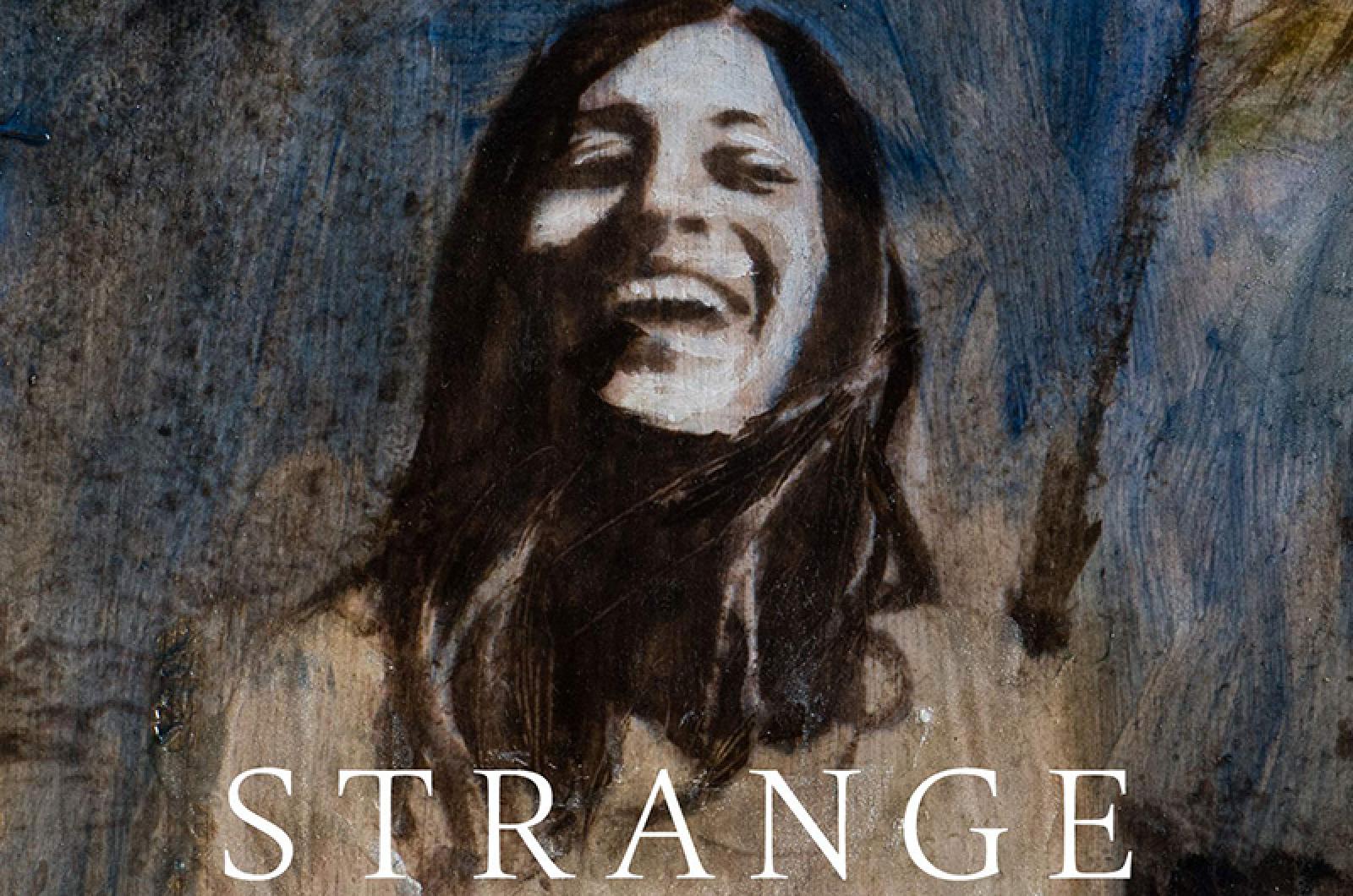

Strange Love by Fred Waitzkin, Open Road Integrated Media, 2021, 133 pgs., $15.99.

The narrator of Fred Waitzkin’s new novel Strange Love had an experience that’s all too familiar to many writers: he peaked early. At age 30, he sold his first book to a famous editor at a big publishing house. He became friends with that famous editor, who brought him around to famous bars like Elio’s, where he was able to talk, however diffidently as the new kid, with literary lions like Gay Talese and George Plimpton. The book was favorably reviewed in the New York Times, and our narrator’s life seemed firmly set on course. But the second book took five years to write, and that famous editor refused to buy it. When it was eventually published, the few minor reviews were favorable, but the dream was clearly derailed.

“I was thirty-five and rudderless,” he recalls. “I wasn’t going to fill a bookshelf like Roth or Updike. What then? For as long as I could remember I was going to be a writer. Until I wasn’t anymore.”

He visits old college friends, but “they were worn out from children, moving on to homes in the suburbs . . . our talk was deadly.”

His dire circumstances eventually drive him to become an exterminator in New York city where he falls under the tutelage of an experienced exterminator named Robert who also comes to fill his hours with incredible stories.

This galling irony — a former writer with a dead muse constantly encountering people who are bursting with stories — only becomes sharper when the narrator ends up years later in the small Costa Rican fishing village of Fragata, where he is instantly enamored of Rachel, the owner of the Fragata Lounge, perched on the water’s edge and sometimes struggling to survive.

He doesn’t tell Rachel about his time as an exterminator in New York.

“It might have appealed to her raunchy humor,” he thinks, “but I didn’t and it seemed too late for revising my story.”

Instead, he fashions himself as a writer with deep literary roots back in New York (in reality, he encounters Plimpton years after their first meeting and the great writer doesn’t remember him), and Rachel is encouraged to tell him her stories. She has plenty of them and he doesn’t hurry her. He accepts the fact that she sets the rhythm of their time together.

“I once said to her, ‘Rachel, I always say yes to you and you almost always say no,’” he recalls. “She smiled at me, softening but not amending what we both knew was true.”

Slowly, over the course of many days and nights in a Fragata Lounge filled with the hot tropical sun or gray salt spray off the rocks, Rachel unfolds the story of her sister Sondra, Sondra’s darling little boy Silvano, and the multi-layered and utterly heartbreaking tragedies that befall the family.

Even while he’s falling deeper and deeper in love with Rachel, our narrator is soaking up all these stories with the eagerness of a scavenger. He remembers how avid he was for stories early in his career, turning every overheard conversation on New York streets or subways into some of those novels he imagined would fill an entire bookshelf. At Fragata, he spends also spends time fishing with the old men and absorbing the patterns of the beautiful, picturesque world around him.

Just as in his previous novel, Deep Water Blues, Mr. Waitzkin conveys that world with the precise, painterly brush strokes: the fishing, the beautiful, changeable weather, the colors and patterns of Fragata Lounge. Readers will feel the salt on their skin. And just as in that previous volume, so too in this one Mr. Waitzkin manages to craft an entire world in little more than 100 pages.

He pays his readers the compliment of respecting their intelligence; there are no easy, pat conclusions in the story. The various storytellers our narrator encounters over the years tie no neat bows on the fever-dreams they spin, and Rachel herself isn’t presented as some idealized dream-woman. And most importantly, the narrator might be a dreamer, but he’s no hero either.

Strange Love is fittingly suffused with stories, moving and memorable. The book is a reminder that those stories are all around us.

Comments

Comment policy »