Cecilia Kang is a reporter for the New York Times, covering the technology field where short and informative sentences are often the norm. Co-writing An Ugly Truth gave the author the opportunity to explore a different kind of writing, one that she missed.

“And that might be one of the reasons why I wanted to write a book. I wanted to get back to more of my narrative writing, my love of narrative writing,” she said.

Ms. Kang did not set out to be a technology reporter.

“I fell into business reporting and technology reporting just by sheer luck and getting my first job at Dow Jones where I worked as the bureau chief in their office in Seoul, South Korea, and I just developed an expertise in it,” she said. “I’m so glad I did it. I think it gives me a different point of view on things.”

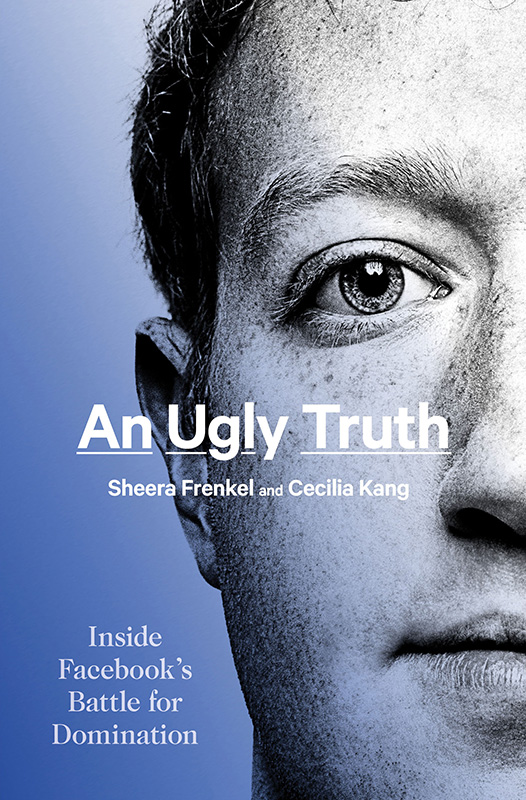

An Ugly Truth began in the fall of 2018 when Ms. Kang and her co-author of the book, Sheera Frenkel, and other co-workers at the New York Times wrote an article called Delay, Deny, and Deflect: How Facebook’s Leaders Fought Through Crisis. The story took readers into Facebook’s decisions that led to election interference and privacy violations linked to Cambridge Analytica.

“There was such a huge response from that and we just knew that there was more we needed to do,” Ms. Kang said. “Not just reporting on sort of the daily scandals that we were reporting on related to Facebook, but to try to connect all the dots about why this was happening, and to really investigate the leadership, the technology and the business model.”

An Ugly Truth is a deep dive into the scandals surrounding Facebook from 2016-2020. This book is the culmination of over 400 interviews with past and present employees and their families, friends, classmates and investors.

“We did not set out to talk to a specific number of individuals but as our book project expanded in scope it just naturally happened that we had to talk to more and more people,” Ms. Kang said. “Our standards were so high when taking on this book project we knew that we could not write about things with only a single source. We needed to verify things with multiple sources, any sort of scene, any sort of conclusion on decisions, anything that we have in the book, especially all the anecdotes, are multiply sourced.”

“It was really the product of just being really careful and astute about the veracity of our reporting. We took the same standards that we take from the New York Times to this book project.”

Although Ms. Kang has been on the tech beat for a while, she was still surprised by some things she learned in the interviews.

“I think a lot of people think they know the Facebook story including us. Sheera and I both approached this thinking we’re just going to put together all the stuff that was on the cutting room floor from our years reporting about Facebook. We’re going to report more and go a little bit deeper, but we were really surprised by a few things. We were surprised by how much we learned that the problems come from design choices. And what I mean by that is, we thought that this was going to be sort of a Frankenstein’s monster story where it was this monster that got away from its creator and just completely went out of control. But that’s not really the case. What we found is that a lot of the problems that we’re seeing right now come from very explicit decisions related to how the business was created and how the technology is designed.”

One of the things the authors discovered is how communication at Facebook would always stop at a certain point. That point happened to be right before it reached the top ranks.

“You don’t have to act on what you don’t disclose,” Ms. Kang said paraphrasing an individual in the book. “I think that there is to a certain extent a hesitancy to reveal too much to the public as well as to top leaders, problems that will slow down the top priority which is scaling the business. Very importantly, bringing bad news to the top executives was not rewarded at Facebook.”

This can be seen in the book when Alex Stamos, Facebook’s chief security officer and other members of the security team attempted to bring reports of Russia’s election interference to Mark Zuckerberg.

“They just stalled at like the legal level, the general counsel and the VP of public affairs,” Ms. Kang said. “A lot of that has to do with those executives saying well we just feel like there’s not enough evidence to bring it forward, but at the same time we questioned why wouldn’t you bring something that’s so new and so novel and so alarming . . . to the top executives.”

The visuals that open each chapter are a constant reminder of Facebook’s continued success, despite the scandals.

“It’s so important for our readers to take away a deeper understanding of the advertising business model and how the ad business model basically uses your attention to sell ads to advertiser,” Ms. Kang said. “And that’s an incredibly successful business model, and that is sort of at the heart of what the truth is that we’re trying to describe.”

The title An Ugly Truth comes from a memo that Andrew Bosworth, a vice president for the company, wrote.

“It comes from this memo that this vice president wrote about how the cost of growth is oftentimes really troubling. Things like deaths, bullying, harm, all kinds of things,” Ms. Kang said. “But that Facebook has made the calculus, and they believe in the long run that connecting the world or getting as many users as possible around the world is a de facto good thing.”

Cecilia Kang takes part in a panel discussion with Jelani Cobb and Andrew Marantz on Friday at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum titled Can Journalism Survive. The event is part of the Vineyard Gazette’s 175th anniversary celebration and is moderated by Don Baer. The talk begins at 6 p.m. with a reception afterward. Ms. Kang also takes part in a discussion with Andrew Marantz on Saturday at the Chilmark Community Center, beginning at 1:30 p.m.

Comments

Comment policy »