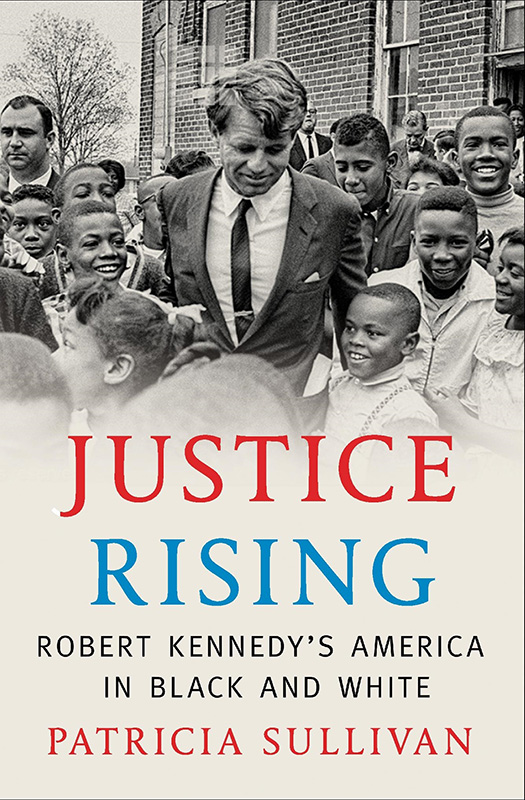

Following Robert F. Kennedy’s path through the civil rights movement, historian Patricia Sullivan said she couldn’t help but well up with emotion writing the last few pages of her new book, Justice Rising: Robert Kennedy’s America in Black and White.

As a researcher, she had essentially inhabited Kennedy’s life and times for the better part of a decade. And now she had to consider what had been lost in that Los Angeles hotel kitchen, where Kennedy was mortally wounded just as his 1968 presidential campaign had gained momentum heading into the Democratic Convention.

“It was just deeply sad and such a loss, and not just the loss of a person, but a loss of a moment, a loss of a future almost,” Ms. Sullivan said in a recent interview at Owen Park in Vineyard Haven. “This country had huge problems and one person couldn’t fix it. But [here was] a person — who was open to pulling our country together and getting the talent at a time when public service really meant a lot more — snuffed out.”

Through the 1960s, Kennedy had gained the trust of many black Americans, long accustomed to unfulfilled promises from white politicians. But after Kennedy’s death, Richard Nixon, who defeated Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey, cynically “harvested the resentments, fears and racial prejudices of the so-called silent majority and built a criminal justice apparatus targeting poor Black urban areas,” Ms. Sullivan writes in the book.

That legacy of inequities and injustices has loomed large ever since.

“What would have been different?” Ms. Sullivan asked, during the interview. “We would have had a chance to move in another direction.”

Now, 50 years later, the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement pose another pivotal moment in history.

“We’ve lost a lot of ground since the 1960s, but I feel that we’re in a moment of racial reckoning, where people couldn’t turn away,” Ms. Sullivan said. “It’s like the sit-ins and what was happening in the Sixties. It was there, and you had to face it.”

A history professor at the University of South Carolina, Ms. Sullivan has devoted much of her career to research on the civil rights movement, including books on the history of the NAACP and the coalition of civil rights activists during the New Deal.

Her life as a scholar brought her to the Vineyard, first in the late 1980s to see civil rights activist Virginia Foster Durr as part of Ms. Sullivan’s first book about the New Deal era. She would later spend extended time with Ms. Durr to edit her letters for another book. Ms. Sullivan eventually bought a summer home here, and last year spent several months on the Island finishing Justice Rising.

“So this history,” she said, smiling, “is my way of coming to Martha’s Vineyard.”

As a subject for a book, Kennedy initially held little interest for her. Like many other scholars, she considered him a peripheral figure in the civil rights struggle. But as she dug into his life, she came to believe he was far more consequential than he had been given credit for.

“This is a story that puts Robert Kennedy at the center of our country at the moment the lid comes off and everything is on the table — the civil rights movement, cities (exploding), people at the breaking point,” she said. “And he is there.”

“And so my interest was how he moves through this, how he responds to what he sees, what he learns, what he does,” she added. “So not too deep into [the research], I was realizing that historians, if they are interested in the Kennedys in relation to civil rights, they were asking the wrong questions.”

She portrays Kennedy’s willingness to not just visit black and other communities of color throughout the country, but to listen and learn from what he saw and heard. One activist, offering high praise for a politician, called him “the last of the great believables.”

“It was who he was. He said what he thought, and people trusted him. And by 1968, he had acted,” Ms. Sullivan said. “He’s known for his great speeches, but as he said: ‘Speeches, what are they going to do? You have to do something.’”

The book argues that he had indeed done the work, first as his brother’s attorney general and later as a U.S. Senator from New York.

By the time of Robert Kennedy’s death, in the space of five tumultuous years the country had lost a corps of young, dynamic leaders to violence, including his brother John (1963), Malcolm X (1965) and Martin Luther King Jr. (1968). So, a train carrying his casket and a large entourage from New York to Washington D.C. — Kennedy was to be buried near his brother at Arlington National Cemetery — seemed to bear much more than the body of the charismatic 42-year-old leader.

Along the way, an estimated 1 million to 2 million people lined the tracks to say goodbye, writes Ms. Sullivan. One of the passengers, Ivanhoe Donaldson, a former Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee activist in Mississippi and Kennedy friend, looked out at the scene with wildly mixed emotions. Along the train route, he would occasionally see police officers saluting, some of them crying, some of them holding black kids aloft to see the casket propped up on two red velvet chairs inside the last car.

“I was trying to bridge the gap between the dream and the reality,” Mr. Donaldson says, in the book. “There was the dream, all along the train tracks [but] in the last car, in that caboose, that was the reality.”

Patricia Sullivan takes part in a panel discussion Friday with Heather McGhee and Vernon Burton titled History: Racism and Exclusion. The panel is moderated by Barbara Phillips and begins at 12:30 p.m. Ms. Sullivan also takes part in an author discussion with Lawrence O’Donnell on Saturday at the Chilmark Community Center, beginning at 1:45 p.m.

Comments

Comment policy »