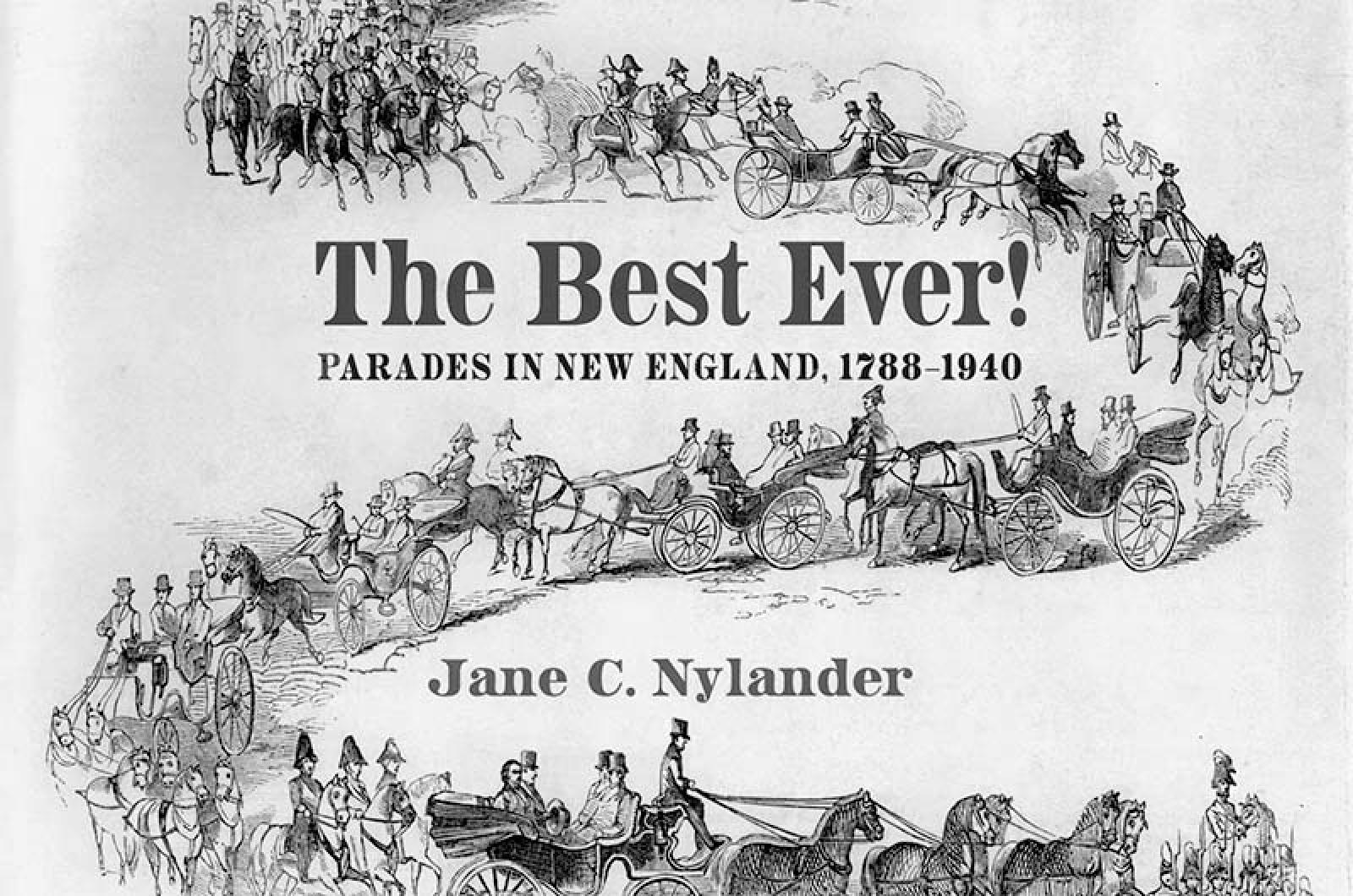

The Best Ever! Parades in New England, 1788-1940 By Jane C. Nylander, Bauhan Publishing, Peterborough, N.H., $45, 384 pages.

Here’s the ultimate coffee table book for every home in New England. At a time when Americans are searching for our national identity, Jane Nylander’s magnificent The Best Ever! Parades in New England, 1788-1940, displays the soul of America, literally on parade and in full regalia.

The book displays generations of fabulously costumed American citizens, young and old, rich and poor, doing their utmost to show you who they are and what they love and believe in. Right there on Main street. In front of the whole world.

With over 320 amusing, sometimes astonishing, pictures, Ms. Nylander, the retired president of Historic New England, documents the elaborate pageantry of dozens of New England cities and towns. No matter how outlandish, absurd or incredible their outfits or the floats they ride on, this volume shows how Americans have found reasons to strut and wave at the crowds and show off their stuff.

Some of the celebrations, grand at the time, seem curious today. For example, on Oct. 25, 1848, three hundred thousand joyful Bostonians saluted the completion of an iron aqueduct that carried fresh water from Lake Cochituate in Framingham to a reservoir in Brookline and then by way of gravity-fed pipes to the city. The jubilant crowd watched a giant procession that marched through the city streets and culminated at the Boston Commons, where the Frog Pond fountain suddenly spurt forth a shaft of the new fresh water to an amazing height of 75 feet.

Images from smaller town parades are equally fascinating. On Sept. 4, 1901, in Norwich, Conn., a horse-drawn float from Prestons’ Hardware features a giant spinning windmill, which displays 1,000 examples of the store’s merchandise. In 1900, the Dennison Manufacturing Company of South Framingham presents a giant Venetian gondola with golden oars, all of it layered with crepe paper and festooned with chains of crepe paper roses. Crepe paper was Dennison Manufacturing’s major product.

The “tableau vivant” — a historical event reembodied by volunteers costumed as iconic figures — was a perennial crowd pleaser. In Newport, R.I. (July 4, 1916) we see Betsy Ross sew stars onto her new flag. In Concord (April 10, 1925) we see defiant minutemen aim their muskets across the Concord Bridge at elegantly uniformed red coats. In North Bennington, Vt. (1907) we see the first Pilgrims grace the shore at Plymouth Rock. These moving tableaux vivants taxed the participants physically because the figures had to hold their stationary poses while their horse-drawn floats rocked and swayed along the several miles of the parade route.

Other scenes are absorbing and endearing. On July 4, 1890, in Lancaster, we see Sanford Wilder, who trimmed his horse and buggy in red, white and blue and donned a long white wig and a tall hat with a starry hatband before driving to the parade with his granddaughter, who was costumed as Lady Liberty.

In 1922, two-year-old Ruth Fairbanks, dressed as an American flag with a silver star on her forehead, stands at attention and holds a flag twice her size. And on August 30, 1924, in Portland, Me., three proud winners grin at the front of a long line of little girls who strolled (less impressively) in the Annual Doll Carriage parade.

A counterpoint to patriotic parades in New England are the “Antiques and Horribles.” These are creatures in sloppy uniforms and grotesque animal masks, sometimes cross dressers, with bizarre slogan-bearing signs and noisy, poorly played musical instruments. The “Horribles’” intention is to be satirical or silly or rambunctious or just annoyingly horrible. The tradition lingers in some Independence Day parades. Who knew?

In her preface, Jane Nylander explains that as a child she grew up watching Old Home Week Parades in Freedom, N.H., a town in the lake district where almost all the citizens (still) participate by building floats or shining up the antique Oldsmobile or marching with the band or donning a uniform or simply standing by and waving a flag. The creativity and originality of the floats fascinated her, and she imagined someday compiling a book about town parades that could recapture the magic.

Though parades have been a tradition in New England since the Revolution, nobody had ever thought to collect photographs of these important town ceremonies and present them in a comprehensive volume. This made Jane’s research for the book strenuous and detailed and time consuming. She poured through thousands of dusty town records and newspaper accounts to find the most interesting or emblematic or affecting photographs and match them with contemporary accounts.

The Best Ever! took 16 years to produce. The result reflects the dedication and expertise of the author, who has plans to speak at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum later this spring or summer.

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »