The Martha’s Vineyard Camp Meeting Association in Oak Bluffs began in 1835 as a small community of like-minded men from Edgartown who wanted to create a location for the religious revivals that were popular at the time. What is known today as the Camp Ground began as a shed and small pulpit, but quickly grew as people built tents and cottages to live in, numbering as much as 200 in 1855.

By 1865 some of those tents and cottages were home to people of color, including those of black and native American descent, according to new research by Andrew Patch, a Washington DC patent attorney and seasonal resident of the Camp Ground who recently became president of the camp meeting association.

An article in 1865 that Mr. Patch discovered documented one cottage built that year that was owned by Samuel T. Birmingham, a black doctor from New Bedford.

“And that was sort of a revelation,” he said in a phone interview with the Gazette last week.

Using digitized records of Camp Ground leaseholders, Mr. Patch said he dug deeper, cross-referencing names with U.S. Census data to determine the race of other early leaseholders. It was a brute force method, he said, but he enjoyed the work.

His full research is due to be published this spring in the Martha’s Vineyard Museum’s quarterly magazine. On Feb. 19 he will give a virtual talk in conjunction with the museum; the event begins at 2 p.m.

What Mr. Patch found in his work was a substantial community of black and Wampanoag cottagers living in the late 1800s on Wamsutta avenue, Clinton avenue and Central avenue, making it the first community of color on the Vineyard. But as he continued to pore over old documents, deeds and newspaper articles, the story of this thriving community of color turned to one of segregation and outright exclusion as homeowners of color were forced out of the Camp Ground.

Cottages on Wamsutta avenue, once home to Dr. Birmingham, D.N. Smith, a minister for Plymouth, and Caroline Becker of Fitchburg, are now the site of a parking lot.

“A lot of those names are still around,” Mr. Patch said.

Then, for much of the 20th century, there is no record of homes that were owned or leased by people of color in the Camp Ground.

Records from the time are illuminating, Mr. Patch said. A report from Oct. 28, 1904 by Edmund G. Eldridge, agent and treasurer for the Camp Meeting association from 1895 to 1926, stated: “It will be remembered that a number of years ago a row of these houses were removed from the rear of Clinton Avenue, and from time to time some of them have been sold and removed for non-payment of rent and unsightly appearance. There are still a number of these shanties in bad repair.”

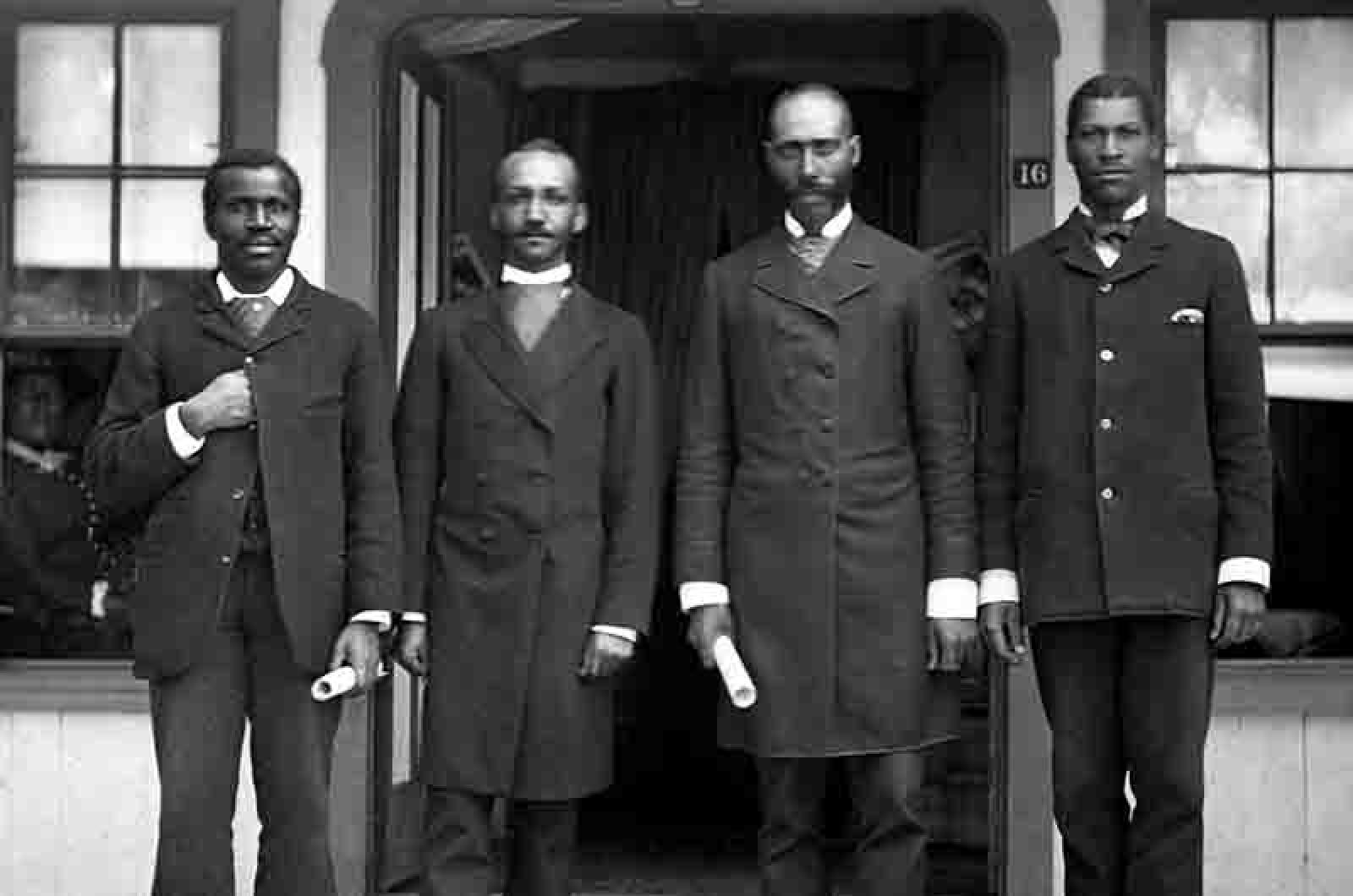

A subsequent photo from the era that appears in Mr. Patch’s research reveals the “shanty” was a pristine-looking summer cottage.

Mr. Patch’s research details how the camp meeting association often used in its annual reports language that tried to deflect any instance of prejudice, while at the same time reinforcing this behavior by their actions. In board minutes from June 13, 1872 an entry said: “Voted that the question of locating colored people be left with the agent.”

Mr. Patch writes: “The above entry suggests that the association at that time permitted people of color to lease lots on the association grounds, but that racial segregation was understood to accompany that practice.”

A story in the Boston Herald dated July 17, 1889, appears to imply a public relations campaign. “Reports that the Martha’s Vineyard Camp Meeting Association has been drawing a color line are unfounded,” the story said. “Some of the neighbors objected to having a colored lodging house next door, and the landlady, who had rented the cottage of a real estate agent, found another one that suited her wants much more fully.”

That many of the residents of color in the Camp Ground had survived slavery and then created lives for themselves in the North made the subsequent racial prejudice on the Vineyard even more stark. Mr. Patch said many Camp Ground residents of color had a connection with New Bedford after escaping enslavement in the South. There many became whalers, utilizing the maritime knowledge gained from navigating the underground railroad, which Mr. Patch said was in large part a path traveled by sea.

“But it must have been one of the hardest ways in the world to earn that money,” he said.

Mr. Patch bought his cottage on Clinton avenue 11 years ago. He said his research began in a casual way, as he searched for old photographs of his cottage. A self-described obsessive, he continued from there, looking for photos of other cottages which led him to the story of the Camp Ground’s beginnings, one that had been buried in the past. Mr. Patch is part of a biracial family; he said the history he discovered hit close to his heart.

“It’s almost like you’re un-erasing a piece of history,” he said.

He said the camp meeting association has a tendency to be insular and even exclusionary. He hopes the research he has uncovered helps the association become more open and reckon with its own history.

“I don’t think you get there . . . unless you acknowledge what you’ve done in the past,” he said.

The chapter uncovered by Mr. Patch has implications beyond the MVCMA, he said, noting that all of Oak Bluffs grew from the Camp Ground.

“The history is connected,” he said. “It’s also very much the tip of the iceberg, what I’ve found so far.”

Comments (9)

Comments

Comment policy »