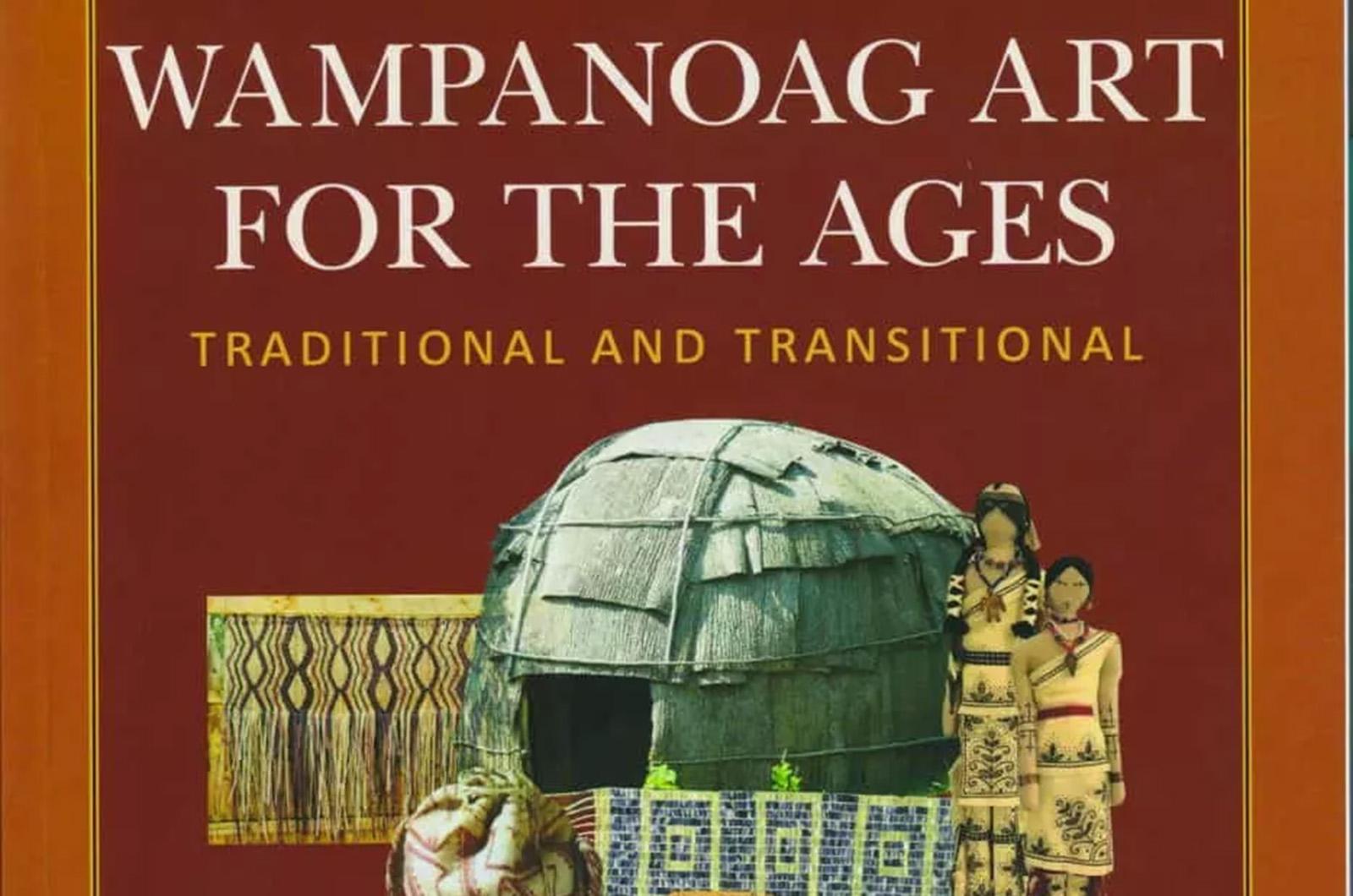

Wampanoag Art for the Ages: Traditional and Transitional by Lee Roscoe, Coyote Press 2022, 77 pages, $20.

It’s been 402 years since English religious pilgrims settled in Plymouth at the native Wampanoag town of Patuxet, and as Lee Roscoe points out in her fascinating new book Wampanoag Art for the Ages, the native society those settlers encountered had already been decimated by diseases brought by European sailors, slavers and explorers. Anyone familiar with American history will know that only more decimation was in store.

Ms. Roscoe points to a fundamental clash of world-views: the Pilgrims set about wantonly felling trees and ransacking their surroundings, setting them at odds with the Wampanoag people who had lived in far greater harmony with the natural world for 12,000 years. The English settlers had money, guns and numbers, but nevertheless, the Wampanoag culture managed to persevere, and in her book, both in her own text and in the many interviews she conducts with Wampanoag artists of all kinds, she stresses “the need to revivify their culture, to bring the past into the present and the future.”

She does this by looking in term at each of the major art forms of the Wampanoag. In eight chapters gorgeously illustrated with photographs taken by a number of hands, Ms. Roscoe describes these art forms in detail. There’s the conception, construction and maintenance of the wetu dwellings, made of supple white cedar saplings and shaped with rounded contours from carefully-harvested local elements. There’s the marvellously intricate matting and twining of textiles into patterns that are both beautiful and practical. There’s the fashioning of various kinds of Wampanoag adornment and regalia.

At each stage of this artistic tour, Ms. Roscoe talks with the native crafters who are the living masters of these ancient techniques. She adds plenty of context to fill in readers who may not be familiar with this kind of native art, and she also lets these various experts help with the explaining. Ramona Peters, for instance, shares her expertise in the history of Wampanoag pottery: “While of Nosapocket’s pots are used as objects of beauty to appreciate, [Peters] reminds us that pots were fully functional, used not only to cook with but for storage of bear grease, whale oil, pigments, water, and even for human ashes as urns.”

Indeed, the main strength of Ms. Roscoe’s book is this generous fluidity of its form; the balance of text, testimony and pictures is perfectly struck. A text-heavy study of native art and craft tradition would have missed in large part the striking beauty of the art itself, and a picture-heavy treatment would have lost a good deal of the human element captured in concerned faces, smiling faces, intriguing workshops and hopeful gatherings displayed in these pages.

That human element is the book’s key stroke of genius: on page after page, we see the faces and hear the stories of the men and women who are keeping the native arts alive, bringing them into the modern moment with a loving combination of tradition and innovation.

We meet Jonathan Perry, for instance, “a consummate carver and jewelry creator” who works to create his pieces in cold-hammered copper, an art our author helpfully explains as “a process by which metal is annealed using heat and quick cooling to make it malleable for expansion, drawing it out into sheet form to shape it.”

Since the copper is not melted and poured into molds, the process requires a sharp eye and a steady hand.

Ms. Roscoe also introduces her readers to Anita Peters, who’s described as “the go-to person for making regalia, traditional clothing worn for ceremony, funerals, weddings, and powwows.” Alongside photos displaying Peters’s exquisite work (including clothing inspired by the work of Teeweleema, the last female descendant of the great Wampanoag leader Metacom), Ms. Roscoe again includes not only histories and descriptions of that work but also conversational interviews with Ms. Peters herself. Despite her historical knowledge, we’re told, she’s also a modern woman, keenly aware of that dichotomy.

“In the past hides were brain tanned, sewn with bone needles. ‘Designs were painted from minerals of graphite, red and yellow ochre, ground up mixed with bear fat applied with a little stick. Now I can go to Joanne’s Fabrics and there are not many bears there,’ Anita quips. ‘Like all cultures, we evolve.’”

That defiant note of optimism, of a culture holding onto its best elements and forging them for the appreciation of new generations, makes Wampanoag Art for the Ages a wonderfully hope-filled thing, a little gem for connoisseurs of native art.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »