Early on the first morning of 2023, as Luanne Johnson and Chris Neill unloaded their tripod-mounted bird scopes from the car trunk, they were greeted by an auspicious visitor: a Felix Neck barn owl, poking its head out to greet the eager birders.

“It’s a great start. They’re a rarity,” Ms. Johnson said, before turning her binoculars back to the sunrise over Sengekontacket and identifying an errant herring gull.

The race was on and he annual Christmas Bird Count had begun, as birders spread out across the Island to spot, count and identify as many birds as possible. It would be a long New Year’s day, starting before dawn and ending in darkness. The birds rarely stayed put, and neither did the birders.

The roots of the Christmas Bird Count date back to 1900, when the Audubon Society encouraged a bird census as an alternative to the 19th century tradition of an annual bird hunt. On the Vineyard, it began in 1960 and has been a valuable resource for avian researchers and enthusiasts alike tracking the Island bird populations.

For ecologist Tom Chase, who has participated in the bird count since 1971, the event has been a great way to gain deeper insight into the changing Island ecosystem.

“You see things over the years and you start teasing out the larger trends,” he said while searching for sparrows in a Lagoon Pond thicket on Sunday.

Birders are deeply attuned to environmental changes, just as birds are sensitive to their climate. At a busy Felix Neck bird feeder that morning, Mr. Neill noted an abundance of Carolina wrens, a species which arrived on-Island after the last four decades of warming climate.

“I know it’s hard to imagine the Island without cardinals, but even they didn’t arrive until the ‘50s,” he said.

Felix Neck was abuzz with avian energy, with several rare species identifications. Among the highlights were an elegant, light cappuccino-colored pintail duck, a flock of energetic yellow-rumped warblers (colloquially known as butter butts) and a brown creeper, a dainty little brown bird that hops its way up and down trees in search of insects.

It was, in Mr. Neill’s birder parlance, “a pile of birds,” with 37 species in total.

It was a rather slower morning for Gazette bird columnist Robert Culbert, whose team covered territory south of the state forest, between Oyster and Tisbury Great Ponds. To aid in his quest, Mr. Culbert employed a secret weapon of winter birders: a recording of bird calls responding to the presence of a screech owl.

“All birds’ alarm songs are fairly similar, so they all recognize each other,” Mr. Culbert said, explaining his use of the calls while looking up into a pitch pine cluster at Sepiessa Point. The screech owl impels the other birds into mobbing behavior, he said, where individuals of all species join to chase off the interloper.

It is a tool used sparingly by birders, given its propensity to irritate the birds. This was evidenced by a precocious chickadee who tried pecking away at the source of the screech owl call: Mr. Culbert’s phone.

On the other side of the Island, Nancy Weaver coordinated her own group off Lambert’s Cove Road.

“I’m not the best birder in the group, but I am the leader,” Ms. Weaver admitted.

While she organized the group's efforts, teammate Margaret Curtin kept her keen ears open for any calls she might be able to identify.

One of their best finds was a bluebird flock near Lambert’s Cove Beach. The group delighted when one individual swooped down from the tree, brought back a caterpillar and ceaselessly beat off its woolly hairs before devouring it in a single bite.

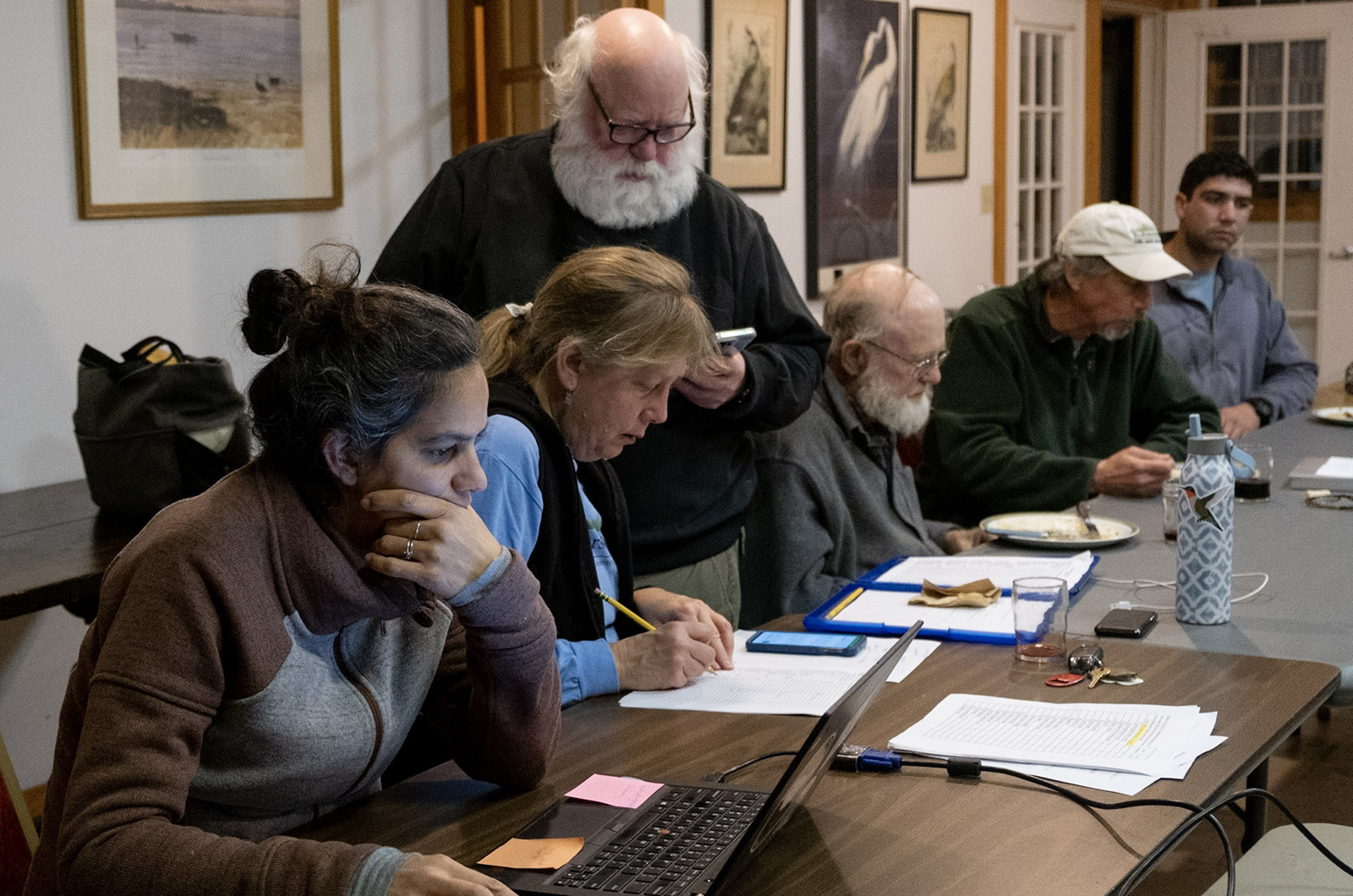

Following long treks through forest, beach and scrub, the bird counters reconvened at the Wakeman Center to compare notes, regale with stories of the days’ adventures and to compile a final tally. Many took note of the unusually pleasant weather for the Count this year.

“Here’s to a Christmas Count in sweaters!” Mr. Culbert exclaimed.

The final tally had ups and downs. Water ducks and sanderlings both came in with historically low numbers, while not a single pied-billed grebe was found. On the other hand, the group recorded 14 greater yellow legs, higher than any other recorded year.

The preliminary tally came to 120 species and more than 18,000 individual birds.

Most birders hung up their hats after the count, satisfied with a good day’s work. For Ms. Johnson, however, the day was not yet done, as she had resolved to go out owling that evening.

“It’s like a treasure hunt,” she explained. “You can always find one more bird.”

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »