The present always holds a little something of the past, but nothing stays the same.

Autumn and winter wipe away summer’s harvest as the year’s crops bear their fruit then wither. New calves are born and grown steer slaughtered.

As springtime turns to summer on-Island, we are on the upswing of that cycle, when plans made as the winter stores grew lean now come to harvest, and ripe produce piles up on card tables at the West Tisbury Farmers’ Market.

The weight of the present moment, the sense that all is cyclical — that all comes in its turn and will return again — is on display in this seasonal, agrarian environment. While perusing Milkweed Farm’s dew-glistened salanova, or the vegetal-purple Kohlrabi of Whippoorwill, or one of Khen’s inflation-proof egg rolls, it almost felt that it had been this way forever.

Of course, it hasn’t, and it won’t.

Perhaps changes in my own life, rumination during my final days on Island before a long sojourn abroad, have heightened my awareness of beginnings and ends. But the Vineyard’s mercurial rhythms don’t escape the notice of anyone who stays here long.

The 50th anniversary of the farmers’ market this year has been a chance, for me, to reflect not just on continuity but on change, and on the world (or worlds) of Island agriculture that so long preceded the farmers’ market, and the local food movement that began decades before I was born.

Long before then, for centuries in fact, a different kind of farmer made the Vineyard home.

I recently had the opportunity to talk to Bow Van Riper, research librarian at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, about the historical journey of those old farmers, one focus of his recent history lecture series. In the library on the second floor of the old marine hospital, where the air smells of fresh paper and old books, he talked me through 400 years of Island history.

“Wool is the big export well into the 19th century,” he said. Indeed, up until that point the Vineyard’s agrarian economy was largely export-based, focused primarily on wool, textile products and some cranberries.

Historians are uncertain as to exactly when the wool industry began — 17th century shepherds, it turns out, weren’t good record keepers. But it was certainly well underway by the late 1600s. The Island was rapidly deforested to make way for the ungulates, causing mass ecological destruction, severely depleting the wild game once caught by Island Wampanoag, who were gradually pushed off their lands.

Meanwhile, the sheep population exploded, reaching 15,000 individuals by the 1770s, around five times the human population of the Island.

A few decades later, the farmers hitched their wagons to the industrial revolution, shipping their wool off to the burgeoning factories in Fall River and Taunton and New Bedford.

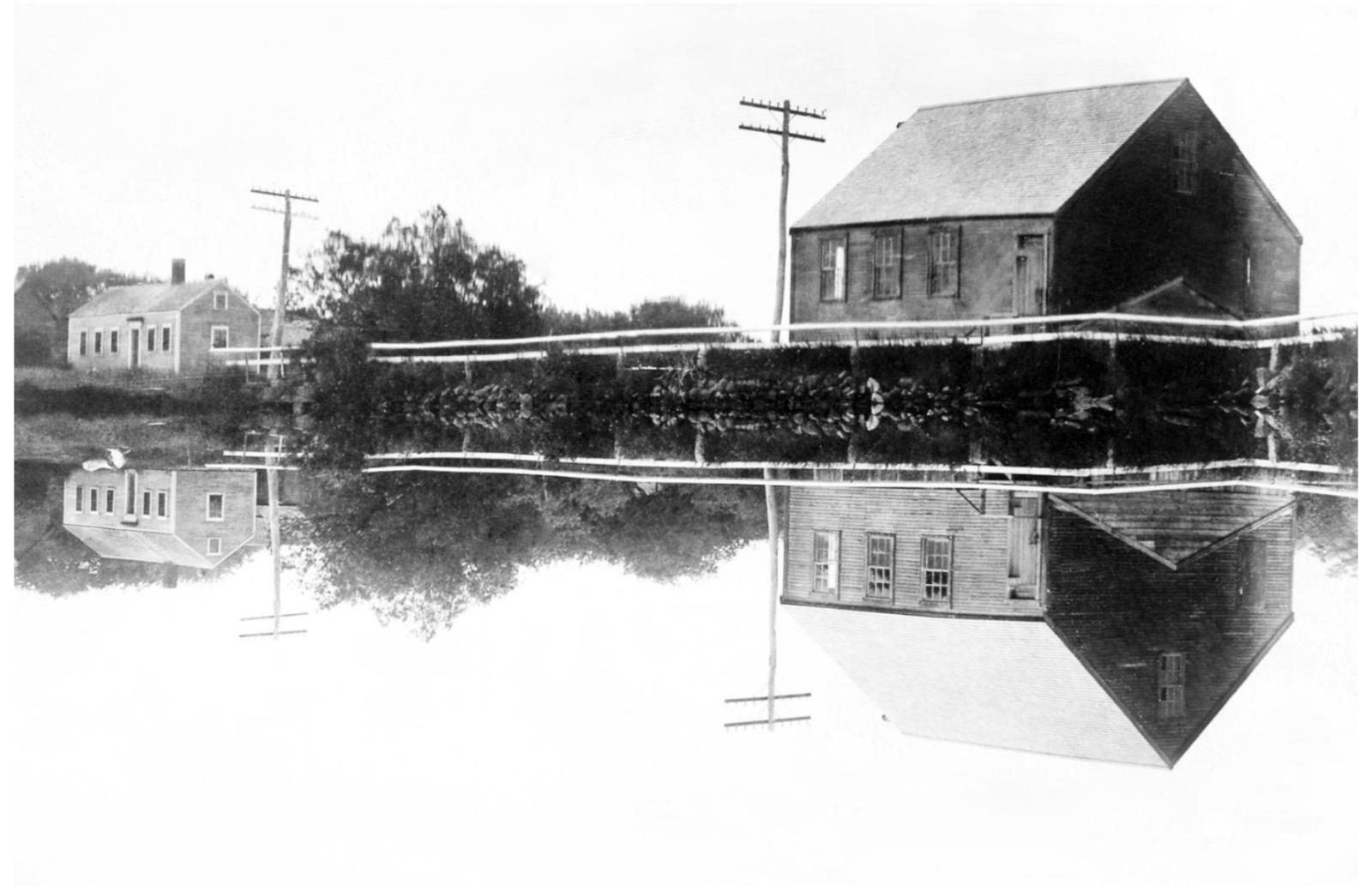

The Island even had its own textile factory, the old mill in West Tisbury. It was “by the standards of the mainland mills, a podunk operation,” Mr. Van Riper said, but still employed a dozen people in its heyday.

By the late 19th century, though, the industrializing nation began to leave the Vineyard behind. Railroads connected big ranches out west to the northeast and the Island lost its edge. The West Tisbury mill held out for awhile by selling to local general stores, but soon those stores were importing cheap, off-Island textiles as well, and business collapsed for the old mill.

But with its dying breath, with its last round of fabric, the old wool mill gave presage of the future, of the little bit of old that still stays with the new to this day.

“The last batch of satinet, produced at the mill in 1873,” Mr. Van Riper, wrote, in an essay on the topic, “was advertised the way a craft beer or artisanal cheese might be today: ‘far superior to any other goods of their class, as they are made of the best of Vineyard wool after the old-fashioned pound to the yard rule.’”

It took some time for the strategy to catch on. It wasn’t until the 1970’s, Mr. Van Riper said, with the influx of wealthier seasonal residents, that a sustained market for the local produce took off. And yet, in that final run of satinet we see the emergence of a local-focused economy that still persists.

And so, when we walk the farmers’ market today, we aren’t seeing a return to some imagined past of Island self sufficiency, nor are we seeing a total break from the past. What we see is the progressive unfolding of history on Martha’s Vineyard, and its fleeting results all concentrated in one moment, in a sunny, breezy field in the heart of West Tisbury.

Little will be the same after another 50 years on the Island, or another 400 for that matter, but a spark of this moment will surely endure.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »