When lone star ticks descended upon the Vineyard about a decade ago, researchers wondered if it would lead to a decrease in the Island’s deer tick population. But after years of surveys, biologists have found that despite the rapid spread of lone star ticks across all six towns, deer ticks have persisted here.

Islanders now have to be on the lookout for two species that carry with them disease and other maladies.

“We just have more of both,” said Patrick Roden-Reynolds, head of the Island’s tick program, who recently co-wrote a study on the tick populations. “It just elevates our public health burden.”

The study, published earlier this month in the entomology journal Insects, delves into how lone star and deer ticks have co-existed since the rapid rise of lone stars, and what it could mean for the future.

Lone star ticks were first found in the southeastern U.S., but the species has crept northward as the warming climate has made more places hospitable for them. Dubbed lone star for the bright white spot on the back of adult females, the ticks gained a solid foothold on the Vineyard around 2014.

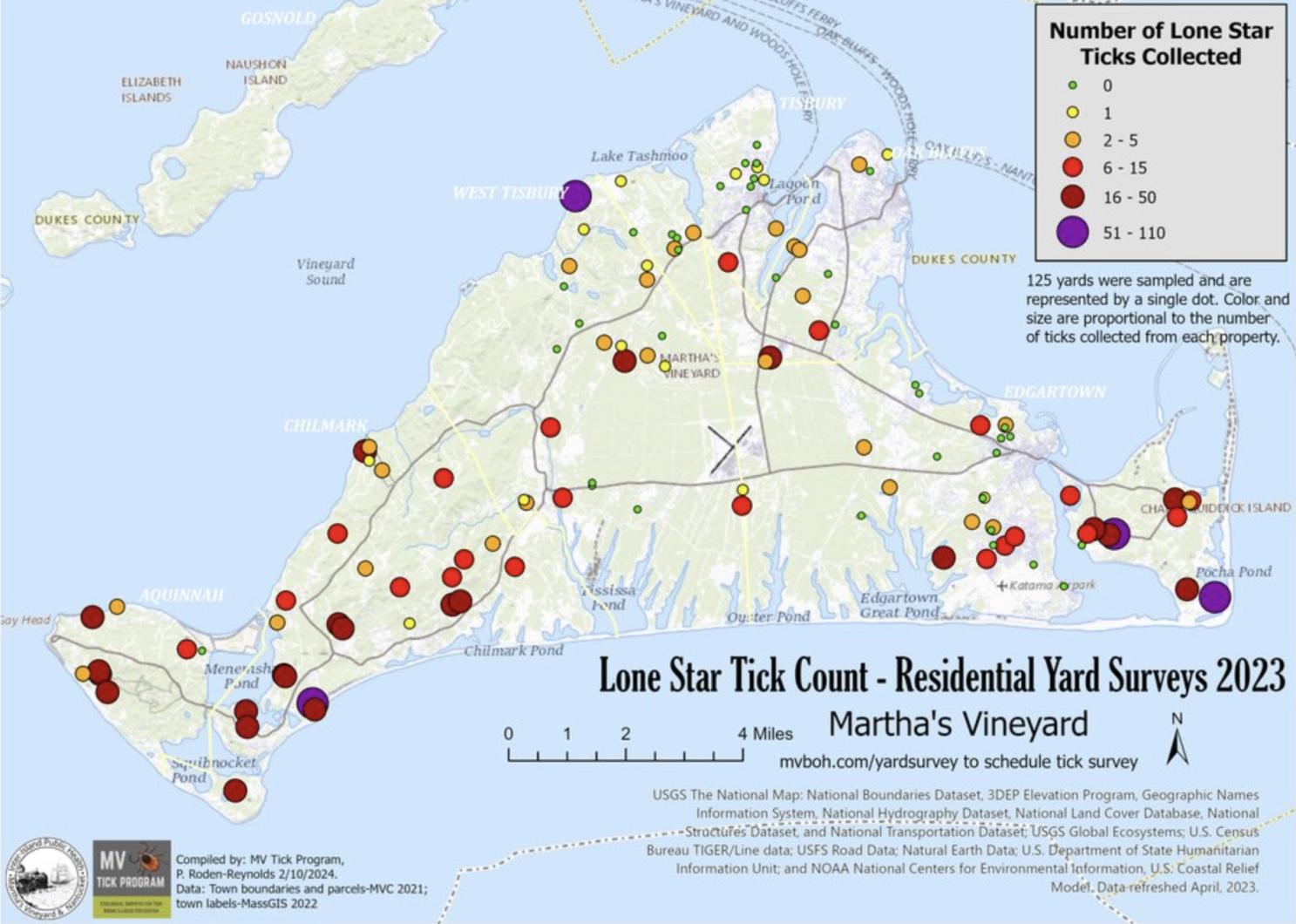

In recent years, they have spread from the Island’s edges — Aquinnah, Chilmark and Chappy — to every town. This summer, the ticks and their larvae are believed to be behind a host of bites and rashes that have sent dozens to the hospital.

Mr. Roden-Reynolds, who worked on the study with Dick Johnson, Allison Snow and Stephen Rich, said when a species enters a new area, they can often displace a similar species in the region. In other parts of the country, studies have shown that lone star ticks have far outnumbered deer ticks where their range overlaps, but there is little research about whether the populations decline directly because of the lone stars.

The Vineyard research, which included more than 1,200 surveys going back to 2011, captures the lone star ticks creeping into the Vineyard and shows they are, at least for now, happily sharing the Island with deer ticks. That could change at some point in the future, but Mr. Roden-Reynolds believes there is more than enough space for the two species here.

“We still have that question, but as of now it remains to be seen if lone stars become the most dominant and common tick,” he said.

Both species bring health concerns. Deer ticks can carry pathogens for Lyme disease, babesiosis and anaplasmosis, while lone stars can spread alpha-gal syndrome — which can cause people to become allergic to red meat and other animal products.

The Vineyard has the highest rate of Lyme disease in the state and Mr. Roden-Reynolds said Lyme remains one of the most prevalent tick-borne illnesses on the Vineyard, despite rising reports of alpha-gal and lone star larva bites this summer.

“Even though people are struggling with this new tick . . . the deer ticks are still out there and are abundant,” he said.

Lone stars could have some advantages over deer ticks when it comes to spreading on the Vineyard in the coming years. For one, they are habitat generalists — able to live in the woods (the deer ticks preferred habitat) as well as lawns. Lone stars also reproduce in higher numbers than deer ticks, meaning their population can become established fast.

Lone stars are also more aggressive. While deer ticks lie in wait for prey to come by, lone star ticks seek out their food, attracted to the CO2 emitted by hosts. Both species primarily feed on the Island’s abundant deer.

Despite the high numbers of ticks, Mr. Roden-Reynolds doesn’t think either species is lacking in potential sustenance.

“There should be plenty of blood, plenty of meals for everyone,” he said. “You would think deer could support both kinds.”

There is one new wrinkle that could forecast the diminishing of deer ticks, though. Preliminary research out of Pennsylvania State University shows that when deer ticks fed on deer after lone star ticks, the deer ticks were not attached to the deer as long and came away with less blood, Mr. Roden-Reynolds said. It is believed that lone stars can trigger an immune-response in deer, making it harder for deer ticks to feed.

More work needs to be done in the field to figure out if deer can become resistant to deer ticks following lone star feeding, researchers said.

For human interactions, because lone star ticks are spread across the Island, it is more likely that people will encounter them in the future, making them a rising threat.

“You had to go under the forest canopy to encounter deer ticks,” Mr. Roden-Reynolds said. “Now lone stars, I think, more people are apt to encounter them.”

Dick Johnson, the Island’s retired tick biologist who contributed to the research, said knowing that both deer ticks and lone star ticks are in high numbers means Islanders need to protect themselves when they go outside.

“Suddenly you have lots of these ticks that are aggressive in places they weren’t before,” he said. “I think it’s going to be a shock for lots of people.”

Old habits of only doing tick checks when walking in the woods need to be augmented with permethrin-treated clothing and other preventative measures, Mr. Johnson added.

“People really need to start paying attention,” he said. “They aren’t just in Aquinnah and Chappy.”

Comments (10)

Comments

Comment policy »