On July 18, 1969, Sen. Edward M. Kennedy arrived on Martha’s Vineyard with his friends and longtime advisors Joseph Gargan and Paul Markham to sail in the 43rd annual Edgartown Yacht Club regatta. His sloop, a Wianno Senior called the Victura, came in ninth.

That was supposed to be the whole story.

Fifty years, and hundreds of anniversary stories later, the sailing regatta is lost to the caprices of history, a memory forgotten from a day the Island — and the world — would remember forever.

“This is no story of a yacht race,” the Vineyard Gazette declared in its July 22 edition four days later. “It couldn’t be. It is, rather, a story of the vagaries of what occurred and a suggestion of what might have been.”

What might have been was a fun-filled weekend on Martha’s Vineyard for the presidential hopeful and the only living Kennedy brother, a weekend replete with Edgartown brunches, old friends and a sailing race that was never supposed to be won. The vagaries of what occurred included a 28-year-old life that was never supposed to be lost, and a little-known summer resort Island that would never be the same because of it.

After the sailing event, Mr. Kennedy attended a dinner party at the modest Sidney Lawrence cottage, tucked into a copse of scrub oak and pitch pine just off the Chappaquiddick Road. In attendance were Mr. Kennedy’s male advisors and six female assistants, known as the “boiler room girls,” who worked together on the campaign of his brother, Robert F. Kennedy. One of those girls, Mary Jo Kopechne, left the party with Mr. Kennedy under the cover of darkness, her purse and hotel room key still at the house. She never returned to get them.

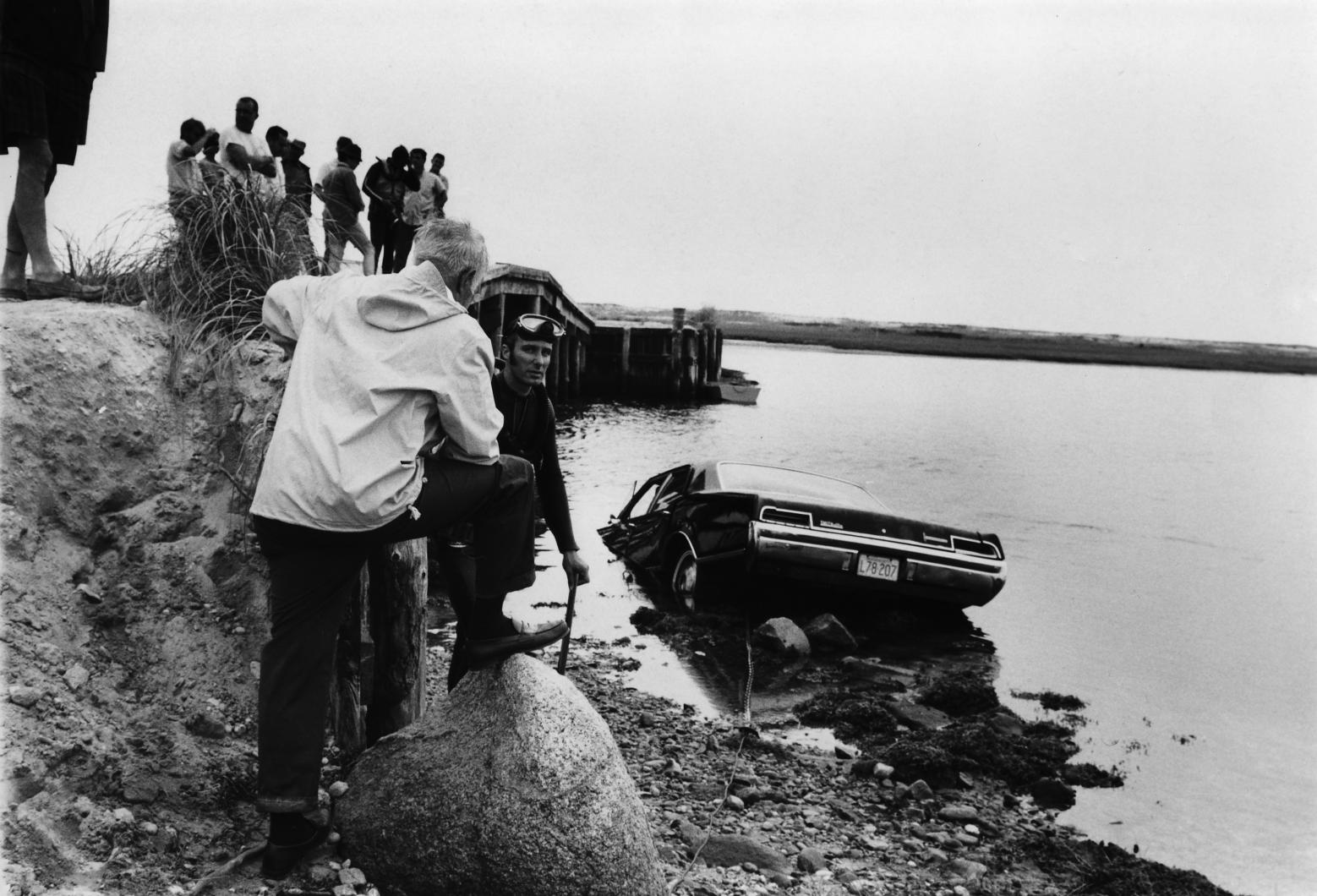

The next morning, Bob Samuel, age 21, and Joseph Capavella, age 15, were returning from an early morning fishing trip at East Beach when they discovered an overturned black 1968 Oldsmobile submerged at the bottom of Poucha Pond just off the Dike Bridge.

Soon after, Edgartown police Chief Dominick (Jim) Arena arrived on the scene and called in John Farrar, an Edgartown diver, to determine if anyone was still inside the vehicle. Mr. Farrar found the body of a woman dressed in a black slacks and a white blouse. Her name was Mary Jo Kopechne. The apparent cause of death was drowning. The apparent owner of the vehicle was Senator Kennedy.

Humans were about to walk on the moon. That could wait.

“Edgartown had never witnessed such a scene before except in a motion picture,” the Gazette reported. “And the throng of photographers, reporters and bystanders in front of the courthouse Monday morning belonged in the fictional world of the movie or of television.”

Reporters descended on the Island, with “flash bulbs flashing, reels grinding, arms raised on high with cameras,” the Gazette noted. They came from expected places, such as Boston, Providence, New York and Washington, as well as unexpected ones, like Chicago, Los Angeles, Italy and London. They packed the Harbor View Hotel, Main street, police station and courthouse, rubbing shoulders with lifelong Vineyarders, who were unaccustomed to the harsh glare of the national spotlight on an Island that had never known it.

“The publicity has put Edgartown in the limelight, given somnolent Chappaquiddick a place in everybody’s gazetteer,” the Gazette reported.

As other newspapers looked for answers, the Gazette reported the questions. And despite the national media coverage, the newspaper of record covered the incident at arm’s length, never wanting to get too close to an event that the Island felt was far too close to begin with. The latest episode in the Kennedy family’s “Greek tragedy,” as the newspaper described it, was exactly that — a Greek tragedy. The Kopechne family’s was an American one.

“Few Edgartonians, however, unlike the rest of the nation, which seemed consumed by the political implications, seemed to forget that the accident was basically a tragedy in which a young woman lost her life, and it is mainly in this respect that all the unanswered questions continue to be worrisome matters,” the Gazette wrote.

The rest of the world thought differently.

“The story of the accident has grown into a story of getting The Story,” the July 25 Gazette reported. “Never on the Island has a single incident been the inspiration of so many individual investigations. The digging for facts that began on Saturday has continued unabated since. The world, it seems, wants to know more than the fact that there was a tragic accident.”

The questions, however, like why the accident was not reported for nearly eight hours, how Mr. Kennedy got back to Edgartown that night, the nature of the party held that fateful Friday night at the Lawrence cottage, and the nature of the senator’s condition when he left the party, would remain pretty much unanswered, forever shrouded in mystery. Meanwhile, the once-quiet retreat in which they took place was bared to the world.

On July 25, “in a voice that was at first inaudible,” the Gazette reported, Mr. Kennedy pleaded guilty in Edgartown district court to a charge of leaving the scene of an accident. Judge James A. Boyle ordered Mr. Kennedy to two months in a house of correction, suspending the sentence for a year on the grounds of Mr. Kennedy’s character and reputation.

The decision effectively ended Mr. Kennedy’s legal trouble. It also ended his political aspirations.

“The defendant has already been and will continue to be punished far beyond anything the court can impose,” Judge Boyle said, climaxing a week when it “seemed as if the Island might sink under the weight of the visiting newsmen,” The Gazette reported.

“Today is the first day I’ve felt like going out to South Beach and just yelling at the top of my lungs,” Chief Arena announced after the court proceedings.

The rest of the Vineyard agreed. The July 29 Gazette described an Island forced to contend with both the physical and figurative debris of its newfound notoriety.

“As far as Edgartown as concerned, events have moved on to a somewhat shoddy aftermath,” the newspaper reported.

That aftermath included souvenir hunters stripping away wood from the Dike Bridge, a “vituperative” box of letters piled on the police chief’s desk, tourists posing in front of the Lawrence cottage, the wrecked Kennedy car sitting at the Depot Corner Service Station, conspicuously shrouded in a tarp to prevent memorabilia collectors from taking its glass. Hundreds of sightseers arrived on Chappy every morning, forming lines at the On-Time ferry that at the time were unheard of.

“And still others, having witnessed with misgivings the behavior of the town in the glare of publicity, wondered if it could ever again be a place where, as in the past, famous men could enjoy its pleasures in relative obscurity,” the Gazette wondered in its August 12 edition.

Today, that is one of the few questions from those fateful few days after the accident at Chappaquiddick that history has been kind enough to answer. The famous men (and women) remain. The relative obscurity does not. And the Island to this day continues to contend with its notoriety.

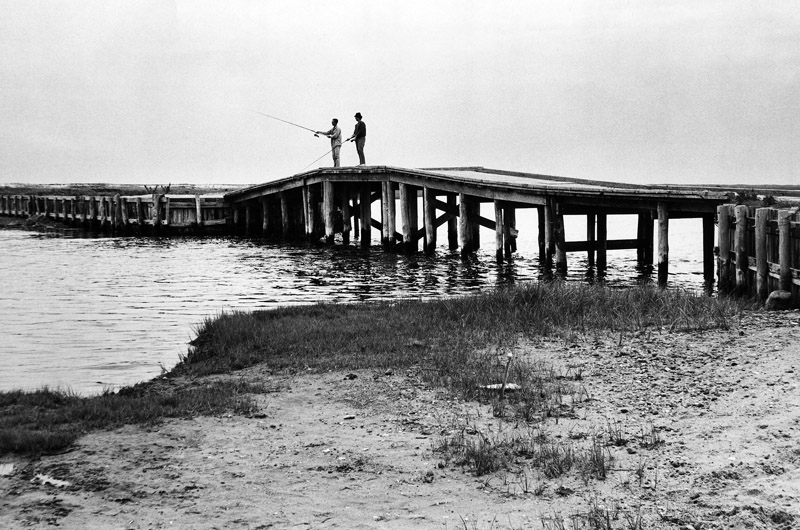

“Kennedy — etc, etc. When is it all going to stop?” wrote Chappy resident Edyth Warren in the July 29, 1969 Gazette. “Here on Chappaquiddick we have been plagued by reporters and tourists. At first it was almost forgivable. But, the tourists . . . What morbid, sadistic curiosity stimulates these scavengers? Here is the quintessence of society in its dimmest light. Let Chappaquiddick return to its tranquility. After all, it’s just a bridge.”

Half a century since, much has changed. Martha’s Vineyard has morphed from shabby to chic, with private jets lining the tarmac at its small airport and private pools hidden behind the stately white-clapboard whaling captain homes of Edgartown and other places around the Island.

But on Chappaquiddick, the Lawrence cottage still stands, the ferry still strives to be on time, and the Dike Bridge is still, as Ms. Warren pointed out 50 years prior, just a bridge.

Although now there are guardrails.

Comments (7)

Comments

Comment policy »