Excerpted from The Chappy Ferry Book: Back and Forth Between Two Worlds, 527 Feet Apart, by Tom Dunlop, with photographs by Alison Shaw and a short film on DVD by John Wilson (Vineyard Stories, 2012).

This excerpt is taken from chapter five which tells the story of James H. Yates of Edgartown, who owned the ferry from 1920 to 1929. He was the last man to run the Chappy ferry as a rowboat.

Folks on both sides of the harbor love Jimmy Yates. But folks on the Chappaquiddick side loathe the ferry Jimmy Yates runs.

James H. Yates is born in Edgartown on July 10, 1876, the son of James S. Yates of the village and Marietta Fisher Yates of Nantucket. Jimmy works in a parade of jobs as a young man on the Vineyard and mainland — grocery clerk, delivery man, assistant plumber, shoe salesman — but after the Spanish-American War he moves to Cuttyhunk, outermost in a chain of islands on the far side of Vineyard Sound, where he fishes and salvages wrecks with his father in law.

Jimmy returns to Edgartown with a daughter and his wife, Mabel, who dies in 1915 at the age of thirty one. He takes over the ferry on the retirement of Charlie and Walstein Osborn in 1920, and for the second time on the Edgartown side, the service moves, from the Osborn boathouse a hundred yards south to a weedy beach just north of the steamboat wharf, the site of the ferry landing today.

It is a startling fact of history — and for Chappaquiddickers, a profoundly frustrating one — that until the day Jimmy Yates retires in the spring of 1929, the Chappy ferry remains a rowboat service.

Throughout the decade, Chappy residents look across the channel to Edgartown and see the equivalent of Paris — a village of electric lights, telephones, paved roads, and drivers of automobiles going wherever they want, whenever they want. Chappy has none of these things, and islanders reckon they never will so long as they let the town get away with subsidizing a rowboat ferry in a Henry Ford age.

In the course of his ownership, Jimmy seldom rows more than two or three people an hour even in summer, which may be why he never shows any interest in bringing the operation into the motorboat and car ferry era. Instead, with Pinafore-like grandeur, he plays up the ironies of his antiquated command, costuming himself in a serge vest with brass buttons, watch chain, and sunflower in his lapel — all this for a service that sails just 527 feet from point to Point.

The paper calls him Commodore Yates, and summer residents on the Edgartown side, joining in the merriment, present him a blue yachting cap embellished with gold braid and a silver badge. “On it is inscribed, ‘Edgartown Ferryman 241,’” reports the Vineyard Gazette. “Just why this mystic number was chosen is a matter for debate but the most popular interpretation is that those who contributed toward the purchase are planning to get two rides for one.”

Jimmy’s ferryhouse faces Dock Street, and next door stands the boatbuilding shop of Manuel Swartz Roberts, now the Old Sculpin Gallery.

Between fares, Jimmy loiters with the Edgartown men who visit Manuel every day. It is a town of pranksters, and Jimmy’s rowboat, beached not seventy-five feet away, is the ripest of waterfront targets. One afternoon, Jimmy hears the bell on the Chappy side and sets off from the beach. A few dozen feet from shore, the skiff halts sharply, and no matter how hard Jimmy rows, he can go no farther – Manuel and the boys have tied a sword fishing line from a wharf to an eyebolt below the waterline of his boat.

On Chappaquiddick, however, Jimmy Yates’s ferry is no joke at all, and as visitors begin to rent houses for the summer in Edgartown, Chappy lags because there is no easy way to go back and forth. On the night of February 28, 1924, island residents take to the floor of town meeting to propose a way around the whole ferry problem. It will cost no more than $100,000 to build, last 400 years, require just $200 annually to maintain, and be paid for by an immediate rise in the value of land on Chappy and the tax revenue that this rise will generate.

What Chappy wants is a bridge.

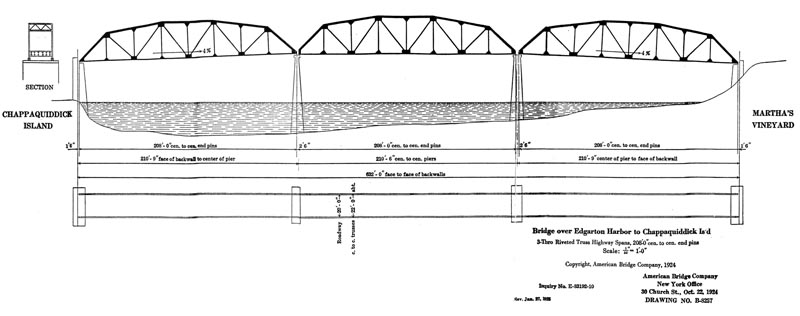

It need not be elaborate, say those who think it up – a footbridge would do at first. As designed by the American Bridge Company of New York City, it looks like a railroad trestle in three spans, each measuring 208 feet, rising no more than 50 feet above the harbor, and crossing at the Narrows where colonial farmers once swam their cattle to graze on Chappaquiddick.

But the proposal leaves out the crucial facts that, as designed, the bridge will land on a private waterfront estate in Edgartown as well as a quarter of a mile from the main road on Chappaquiddick. That once on the Edgartown side, those who use it will still face a mile long walk into town. And that 50 feet is too low for the masts of the largest sailboats to clear as they sail to and from Katama Bay. It takes a year, but at the next town meeting, Edgartown voters turn down the bridge idea, 99-58.

Chappaquiddick quickly raises the stakes. Six months later, in August 1925, all sixteen voters on the island, together with thirteen other landholders, file a petition with the state to separate from Edgartown and incorporate as the town of Chappaquiddick.

Chappy has one asset that it can hold hostage as Edgartown considers a response — access to the valuable shell fishing grounds at Cape Pogue Pond. Edgartown brushes aside the threat: At the next town meeting — which Chappaquiddickers boycott — the town votes symbolically 108-1 against Chappy independence. It also votes to hire a lawyer to protect its interests.

On the rainy afternoon of April 8, 1926, members of the state legislative committee on towns visit Chappaquiddick to determine whether it should be allowed to go its own way. Jimmy Yates rows the committeemen over to the Point for a tour, and at least one problem to do with the ferry presents itself when Representative Josiah Babcock of Milton, believing the skiff has landed on the beach, steps over the side and into water up to his waist.

Three hundred citizens attend a committee hearing held that night at town hall. Benjamin W. Pease of Chappy testifies that fifty-three people have left the island in his lifetime because of the poor ferry and refusal of Edgartown to meet basic island needs. When his father died one winter, Ben says, Edgartown charged his mother $100 to clear the road of snow so that the body could be brought to town for burial.

Yes, the ferry is “rotten,” concedes Benjamin G. Collins, a town selectman, but the village carries too much debt to build a bridge. There is already a motorized launch to the bathing beach in summer, he adds. And most Chappaquiddickers have their own boats anyway. “If it wasn’t for the $100,000 yearly shellfish catch, the grounds of which are mostly in Chappaquiddick waters,” he declares, “I would say, ‘Go and God bless you.’”

It’s not known whether Jimmy Yates attends the meeting or how he responds to hearing his ferry characterized as rotten — other descriptions include “hazard” and “disgrace” — but it is no surprise when the committee refuses to endorse the creation of a new town of just sixteen voters. Yet legislators depart Edgartown with the pointed remark that they know “no parallel in Massachusetts of an island dependency effectively cut off from its parent town.”

Edgartown takes the cue — if it ever wants anything from the state again, it had better do something about this problem soon — and in February 1927 the town meeting commissions Manuel Swartz Roberts, a village boatbuilder, to build the first town-sponsored boat for the Chappaquiddick ferry. But the new boat is nothing more than a $250 barge, designed to carry a single car, and no provision is made to build or buy a powerboat to tow it.

Thus it becomes one of the wonders of the age to see Jimmy Yates, at sixty-one, pulling the barge loaded down with a Model A across the entrance to the harbor. Together, car and scow can weigh nothing less than two tons. Yet the challenge is one not just of weight, but also of current: In 1921 the town digs a new cut through South Beach — an opening created by a storm in 1886 having closed naturally in 1903 — in the belief that the shell fishing beds in Katama Bay do better when the harbor is connected directly to the sea.

As a result, the tides once again funnel through the harbor entrance forcefully, and Jimmy must wait for those rare moments when the currents slacken just long enough to pull across the barge and car. On occasion he finds another man to help haul from a second boat. But not often. “Years of pulling at the oars made the ferryman’s arms tremendously powerful,” says the Gazette after his death in January 1942.

The most mysterious thing about the tenure of Jimmy Yates is what happens at the very end of it. In the spring of 1929, the town finally builds a power launch to tow the barge and cars — at a cost of $2,015, with Manuel again the builder.

But as the new motorboat goes in the water, Jimmy quits. A 19th-century man to the last day of his service, he apparently wants nothing to do with the sort of traffic a mechanized operation will surely bring. With his yachting cap, badge, and sunflower boutonnière, Jimmy Yates and a rowboat era lasting more than 125 years depart the annals of the Chappaquiddick ferry.

Replacing him as ferryman is a boyhood immigrant from the Azores, short of stature, and visionary in thought and deed.

On Saturday, June 30, from 5:30 to 7 p.m. there will be a book launch party for The Chappy Ferry Book held at the Chappaquidick Community Center. A second launch party will be held on Sunday, July 1 from 5 to 8 p.m. at the Old Sculpin Gallery in Edgartown (located next to the Chappy Ferry dock). Throughout the summer there will also be numerous readings and discussions. For a full list of events, visit vineyardstories.com/calendar.php.

Comments

Comment policy »