Yesterday he was the seven-year-old boy who grew up and played on the grounds of the Mystic Seaport Museum with his twin brother. Sometimes they would climb through a vent in the creaky old Charles W. Morgan to hide and make noises to scare visitors who were touring the ship.

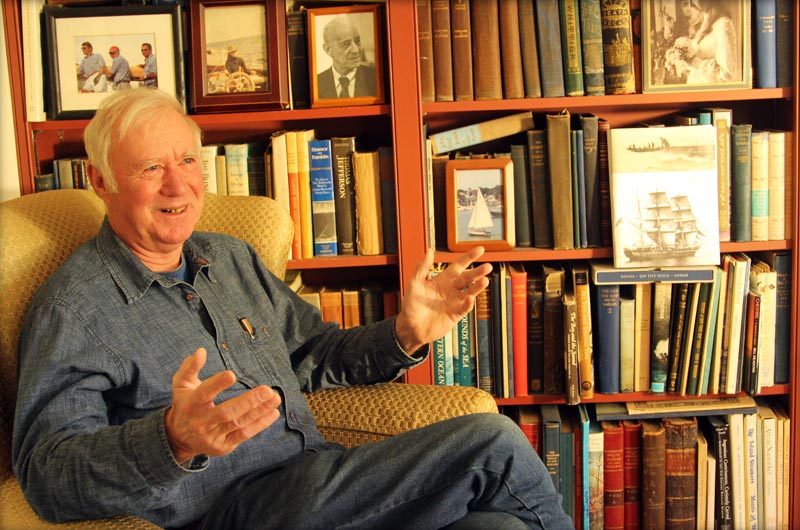

Today he is the 67-year-old historian for the Morgan, at home in West Tisbury and settling into a corner chair in his den on a windblown last day of May, flooded with sunshine and memories.

If the Morgan is the lucky ship, then surely Matthew Stackpole was born under her star.

“I pinch myself,” he says. “We’re living history and in doing so, we’re bringing back history. I’m the luckiest guy. I can’t tell you.” In two weeks the Morgan will sail for the first time in some 92 years and Matthew will be on board. But that’s near the end of the story. This was a day to return to the beginning.

Sitting in his den, surrounded by the trappings of his life — old books, prints and photographs — the tales tumble out, Matthew Stackpole-style. Stories layered with more stories. Deep reverence for some of the great historians such as Nathaniel Philbrick and David McCullough. Laughter, tears, repeat.

He was born on Nantucket, the son of Edouard Stackpole, a newspaper man and linotype printer who worked for the Inquirer and Mirror, the weekly newspaper of record for the Vineyard’s sister island that is still published today. The senior Mr. Stackpole was also a writer.

“Dad always had an interest in history, he wrote historic fiction, he wanted to know about our ancestors and once he started reading log books, he disappeared into whaling. He got a Guggenheim fellowship to write a book about Nantucket whaling history . . . . because of that book, Mystic hired him to be the curator in 1953 and we moved there. We grew up on the grounds of the museum. You know a Night at the Museum? Well, we spent a decade of nights in a museum. That was our life.”

High school was followed by college at the University of Connecticut. In the summer of 1965 he went to Mystic to work as a rigger, including on the Morgan. In 1966 his father left his job at Mystic and returned to Nantucket.

Matthew, still in college, was deciding where to work during his summer vacation. “I wasn’t very good at much of anything. I went to see Art Kimberly, head rigger of the Morgan. And I said will you hire me back? That was 45 seconds that changed my life. He said, sure I’d hire you back but don’t you want to work on a boat that moves? I said but who would hire me? He said there is this guy Bob Douglas, he has this boat that he built, a schooner. He might hire you.”

So he went to work for the summer as a deckhand on the Shenandoah. “Rick Burroughs was there, too,” Matthew says, ticking off the names of others. “The reason the Island is so overpopulated is because so many of the crew of the Shenandoah stayed,” he adds with a laugh.

The next summer he became a bosun, then a mate, and later got his 100-ton license. “We sailed her hard,” he says of the Shenandoah. “There was a real art and camaraderie to traditional sailing and doing it right.”

A favorite story about the Shenandoah was the day they became fogbound on Nantucket and Matthew’s mother baked an apple pie to send out to the crew. “Bob loved that pie and every time we were near Nantucket after that, Bob would say, why don’t you call your mother and tell her you are coming?” Following captain’s instructions, Matthew called ahead one day to let his father know Shenandoah was on her way. “This was before the days of cell phones and it was all done on the marine radio.” Anchored off a sandy beach at Brant Point, Shenandoah was photographed that day by Edouard Stackpole in what would become a famous print, done in the Currier and Ives style, and later sold by the Mitchell Gallery on Nantucket. Today a framed print hangs in Matthew’s den. He gazes at the photograph. “The day they took that picture, we owe it all to the pie.”

In 1968 Matthew graduated from college and began to teach school at the Dana Hall School (history, naturally). While there, he met Martha Foley and in 1971 they were married. They spent a summer driving across the country and agreed they wanted to own a sailboat. They bought the 50-foot Concordia schooner MYA, living on her in Vineyard Haven in the summers and chartering her.

Later they bought a piece of hilltop land in West Tisbury that was part of the old Merry Farm, and built a house, traditional in style, 28 by 32 feet in size, nestled into a high meadow. The architect was Peter Phillips, a friend they had met during their schooner racing days on the MYA. The Stackpoles raised their two children there and it remains their house today. Matthew credits Martha with everything good that has happened to him in his life.

“I couldn’t have done any of this without Martha,” he says quietly. Sometime in the early 1980s, he can’t remember the exact year, a job opportunity arose when the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital was hiring a development director. Matthew wanted to try it. “I was asked why I wanted the job and I said I’m here and I want to help and I believe in the place.” The hospital board was led in those days by the late Thomas Mendenhall, retired president of Smith College, and the Very Rev. Francis Sayre, former dean of the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. “Tom and Frank were both mentors to me.”

Except he didn’t get the job at first. “They hired the other guy,” he recalls. On the same day he learned that news, Matthew was walking on the beach and ran into Tom Mendenhall. Turns out the person the hospital hired had a change of heart about taking a job on the Island. The job was Matthew’s if he still wanted it.

He took it and stayed for 11 years.

Then he went to work for the late Dr. David Smith, a doctor, award-winning scientist, philanthropist and conservationist who founded the Polly Hill Arboretum. “My jobs on the Vineyard took me into so many different corners,” Matthew says. “I learned so much from David, about philanthropy and conservation. He was visionary.”

After that he went to work for the Martha’s Vineyard Museum as its development director. “I learned from my father that history is about human beings, it’s not facts, it’s people,” he says. “I had a strong sense of what the museum could be. Its collections were so pure.”

He left the museum in 2007 and found himself once again at a crossroad in his life.And then the phone rang. It was Mystic calling.

“When I left the museum, I didn’t know what I was going to do. It was December. I was sitting in my house and Doug Teeson [president of Mystic Seaport] called. He said I understand you might be available, we are looking for someone to help raise money for the Morgan. I was sitting here looking at this sketch which had belonged to Dad.” The framed sketch of a schooner by maritime artist John Stobart sits on top of a desk. He turns it over to show that the sketch was done on the back of a grocery list. Milk, bread, sketch the schooner.

“It was this wonderful opportunity to go back, go home, to the place where I was in 1965,” he says.

Initially the job was to raise money for the Morgan, and he was thrilled to become part of the project. “To be able to ask for funds, to be able to tell the story, it was all familiar to me,” he says. Later Matthew was named ship historian and it’s obvious that the role fits. He knows every detail of the Morgan’s long, remarkable history, lives and breathes it, can tell it over and over again, reweaving the fabric slightly every time, never tiring from the telling. “It’s been a joy to have this responsibility,” he says.

Now the Morgan is rebuilt and ready to sail and Matthew is crying. He says there was no one big moment at which it all became clear, but in fact a series of them: when she was floated last summer for the first time as a rebuilt ship, when she left the wharf for the first time last month to be towed down the river to New London, when the captain’s instructions were called out over the marine channel — “Security, Security, bark Charles W. Morgan, underway.”

“All of us were like, how can we be surprised, we’ve been working on this for so long, but then it become real,” he said. “Someone asked me what it was like . . . it is very emotional, it’s a dream come true. It’s been just a gift — for Gannon and Benjamin, for the Vineyard. It’s truly our history and I had the good luck to be a part of it. I can see the whole thing in my mind’s eye. I see the film over and over, I see her coming apart and put back together again.”

And when she comes down Vineyard Sound it will happen all over again, and the same will be true in New Bedford. Every leg of the 38th voyage holds special meaning, and Matthew Stackpole is steeped in it. “My daughter said to me when the Morgan sails into New Bedford there will be a ghost fleet of 2,700 behind her,” he says.

“I wake up in the night and say am I really here? It’s euphoric. You can’t explain it. You can’t predict it. I’ve had amazing good luck. It’s allowed me to think about things that are meaningful in my life and my family’s life and this is an overused word but it’s a privilege. To sail one more time on a whaleship? My goodness.”

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »