The deaths of Michael Brown, Freddie Gray and many others at the hands of police in recent years have sparked conversations and protests around the country.

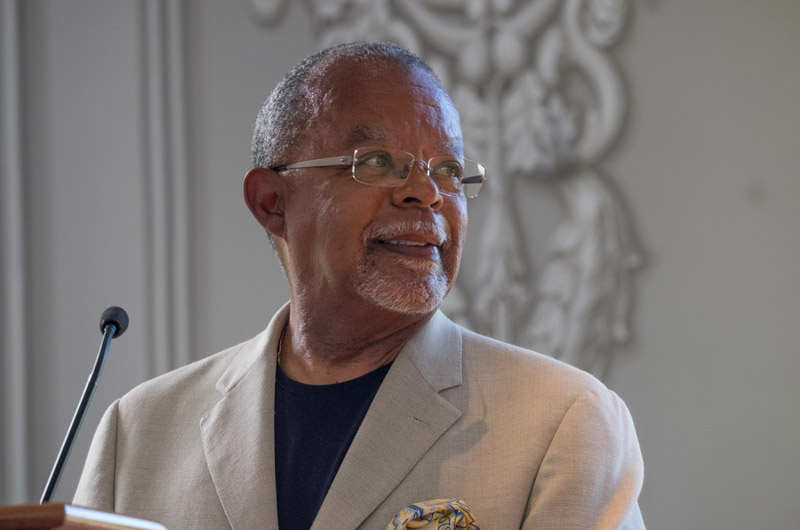

“Their losses shocked us all, and shocked some of us to organization and action,” Henry Louis (Skip) Gates Jr., director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University, said last Thursday. Mr. Gates was speaking to a large crowd gathered at the Old Whaling Church in Edgartown for the 20th annual Hutchins Forum.

Black Millennials: They Rock, But Can They Rule? featured several young professionals who are also active in civil rights issues, and looked ahead to the next 30 years. Four of the five panelists were born between about 1980 and 1995, earning them a label that may evoke more disdain than admiration.

“The picture that emerges about these millennials is complex,” said award-winning journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault, who moderated the forum. She noted some opinions that millennials are self-centered, careerist, dispassionate, entitled and narcissistic.

“The workplace has become a psychological battlefield,” she said, quoting Morley Safer of 60 Minutes, “and the millennials have the upper hand, because they are tech savvy, with every gadget imaginable almost becoming an extension of their bodies.”

But many are also civic-minded, she said, and have helped spread the message of movements like Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter around the world.

“There is a difference between black millennials and white millennials,” said panelist Janaye Ingram, executive director of National Action Network, a civil rights advocacy group. She said black millennials must work harder for opportunities like college and jobs, while facing an unfair criminal justice system that white people might not even think about.

DeRay Mckesson, a prominent activist and organizer who had also joined a panel in Oak Bluffs on Wednesday hosted by the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute, didn’t object to the “Generation Me” label. Instead he praised the conviction of young protesters in Ferguson who refused to go home in the months after the killing of Michael Brown, an unarmed teenag

Technology has allowed protesters to stay informed and connected, he said. “We always face issues of erasure . . . . Either the story is never told, or it’s told by everybody but us. And when I think about Ferguson, we literally became un-erased.”

As with the forum on Wednesday, the conversation focused largely on how to define success — a question that may rest more in the hands of millennials than those of earlier activists.

Journalist and commentator Dion Rabouin saw himself as both the self-serving and community-minded millennial type. He disagreed that his generation was disaffected, pointing out that “we are the people who elected Barack Obama,” and that presidential candidates are now pursuing young voters.

“We’ve got a lot of things at our fingertips at all times, and I think that can be annoying on a person-to-person level,” he said, “but it’s because a lot times we are informing ourselves about the world.”

Charles F. Coleman, a trial attorney in the New York District Office of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, was one year shy of being considered a millennial. But his views were largely in line with those of other panelists.

Frustration with an unfair criminal justice system can make people lose hope and give up, he said. “I think that there has to be a balance between a desire to change the system as a whole and also learn how work within the system as best that we can to our advantage.” But he worried that millennials might not be willing to help create a new system.

While looking ahead, the panelists also looked back at the civil rights movement over the last several decades. Ms. Ingram noted that key organizers had nearly missed the March on Washington in 1963 because they were meeting with legislators. She advocated for a ‘demonstration to legislation’ strategy, where lawmaking and activism go hand in hand.

Mr. Coleman said he would like to see Black Lives Matter evolve into the left’s version of the Tea Party, with a specific agenda that would challenge both Republicans and Democrats.

Orlando Watson, communications director for black media at the Republican National Committee, provided some balance on the panel. He agreed that the next steps for the movement were to organize and put pressure on institutions, but he also criticized black millennials who lobby politicians to create change. “That’s outsourcing our agency,” he said. “It hurts me to see.”

On a different note, Mr. Mckesson said activists can at times be paralyzed by a flood of information and advice, preventing decisions from being made. He also worried that many people are still unable to imagine new forms of power. “Part of the work will be removing barriers, and then the other part of the work will be building and rebuilding,” he said. “Sometimes we can be too addicted to the fight and not enough to the win.”

On Friday, Black Lives Matters unveiled Campaign Zero, a 10-point plan to address police abuses of power. Among other things, the plan calls for civilian oversight in cases of police misconduct, clear limits on the use of deadly force, and an end to “broken windows” policing, which focuses on small crimes as a way to prevent larger ones.

“Campaign Zero was informed by the demands of protestors nationwide, research, and input from many folks,” Mr. Mckesson tweeted Friday evening.

Ms. Hunter-Gault asked the panelists for their advice on how to narrow the race divide. Mr. Rabouin emphasized the importance of money in a capitalist system and how black communities could benefit from affirmative action — a straightforward argument that the audience applauded.

In contrast, Mr. Orlando painted the African American community as a political force with more than $1 trillion in purchasing power, and more college graduates today than in the 1990s. But he also encouraged people to “challenge systems that stifle opportunity in whatever way that you can.”

A question and answer period touched on the issues of black-on-black violence, the weakening of protections under the Voting Rights Act, and how to work with the older generation of activists.

“The new guard needs to learn that . . . there are lessons to be learned,” Mr. Coleman said. “The old guard needs to learn that sharing the mic or passing the mic does not mean leaving the stage.”

In closing, Ms. Hunter-Gault asked the panelists what they saw as the biggest challenge in the next 30 years, when people of color in the United States will become the majority.

Mr. Rabouin hoped to see people harness the power they already have.

“One of the things we fail to do a lot of times is really understand how powerful we are as individuals and as groups,” he said. “Once people of color are the majority, I hope we’ll be able to understand that we have the power to change things.”

“And you will be ready to rule?” Ms. Hunter-Gault asked.

“Absolutely,” Mr. Rabouin said.

Comments

Comment policy »