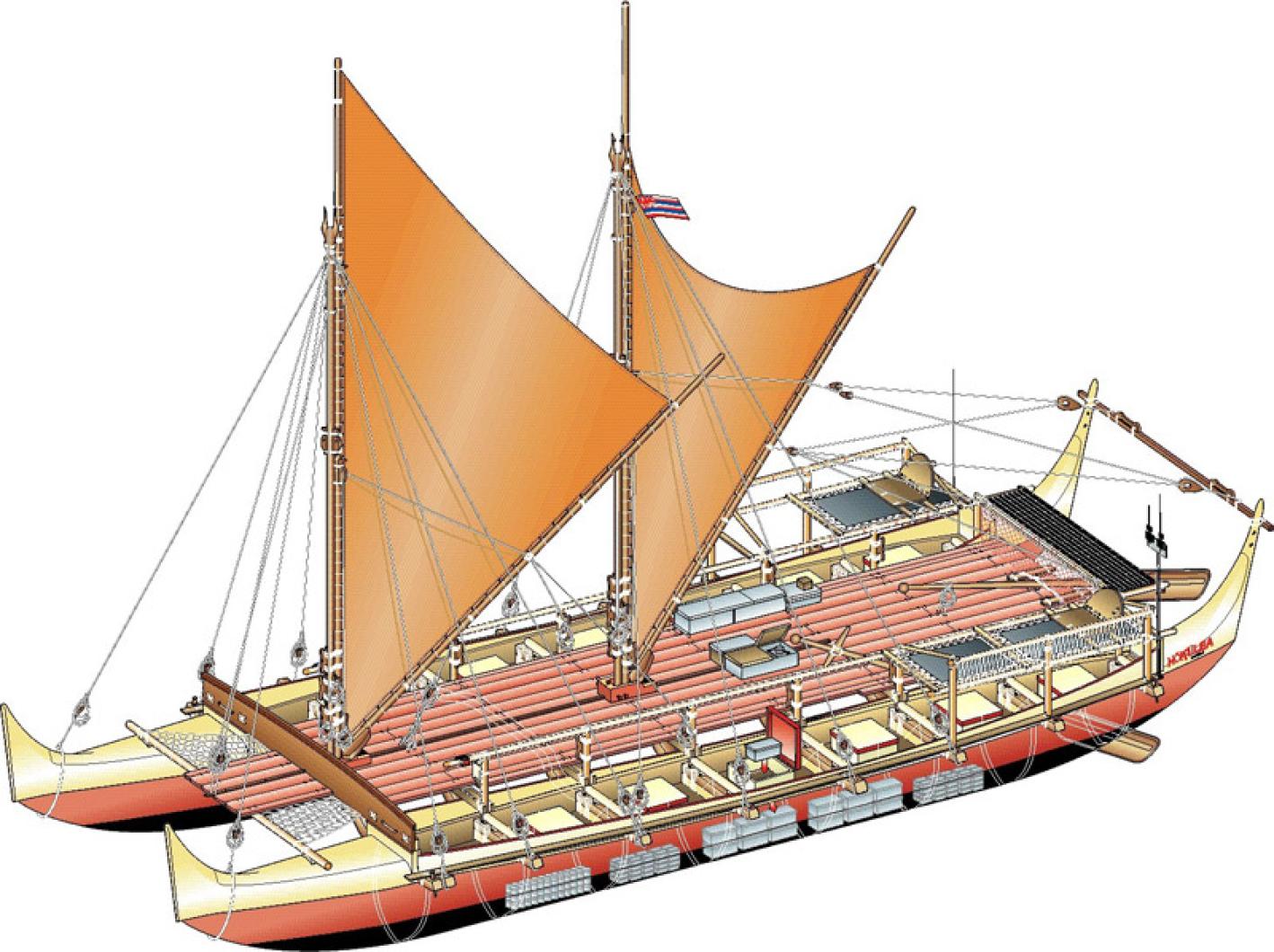

To a modern sailor’s eye, she appears strange. Her twin hulls are joined by laminated wooden crossbeams and fastened to them by six miles of rope lashings woven into complex patterns reminiscent of the art of M.C. Escher. A deck is lashed over the crossbeams. The hulls rise up sharply at bow and stern and terminate in a graceful arc, called a manu, where wooden figures with high foreheads and protruding eyes, the aumakua or guardian spirits, stare out over an empty sea. Viewed from above, the canoe’s strangeness is dispelled. She looks like a catamaran.

Hokule’a is a replica of the vessels used by Polynesians to settle one-third of our planet a thousand years before Europeans knew the Pacific Ocean existed. Launched in 1975, she has sailed 150,000 miles, following the routes taken by intrepid Polynesian explorers, navigated always as they would have done — without instruments or charts — by relying instead on signs in the stars, waves and flight of birds. In July, Hokule’a will visit Martha’s Vineyard on a voyage around the world to malama honua, care for Planet Earth.

Hokule’a’s shape is ancient but her construction is not. A thousand years ago, her sails would have been woven from Pandanus fronds, but no one knows how to do that today, so they are made of Dacron. Her hulls are fiberglassed marine plywood because the art of carving such canoes from live wood has vanished along with the ancient canoe makers, the kahuna kalai wa’a. She is a performance replica, designed to perform like an ancient vessel by using plans made by European explorers of the canoes they encountered in the 18th century.

“We wanted to test the theory that such canoes could have carried Polynesian navigators on long voyages of exploration throughout the Polynesian triangle,” said navigator Nainoa Thompson, “We wanted to see how she sailed into the wind, off the wind, how much cargo she could carry, how she stood up to storms. Could we navigate her without instruments? Could we endure the rigors of long voyages ourselves? Frankly, that was enough of a challenge. It didn’t matter if the canoe was made of modern materials as long as she performed like an ancient vessel.”

Hokule’a is 62 feet long, displaces about eight tons and carries a cargo, including her crew, of six tons. Sailing with a strong wind behind her, she rockets along at 15 knots. Sailing into the wind, on a voyage between Hawaii and Tahiti, she averages about five knots and a 2,400-mile journey usually takes about 25 days.

We sleep in the hulls, in small compartments about four feet wide and six long, covered by a tent stretched over the handrails. We cook on deck using a two-burner propane stove encased in a waterproof box. To go to the bathroom you walk aft, crawl under the handrails, stand on a narrow catwalk and hang on.

I first sailed aboard Hokule’a in 2000, on a voyage from Tahiti to Hawaii. Five years earlier, I had made the same voyage on a 40-foot sloop of impeccable modern design. The voyage turned out to be a severe test of endurance and patience. The sloop heeled over in the trade winds — about 30 degrees from vertical — and thrashed her way through heavy swells. We lived in a canted, pitching world for three weeks, emerging from that experience thrilled but exhausted.

My voyage aboard Hokule’a was quite different. A sailing vessel with a single hull like the sloop heels away from the wind, but Hokule’a distributes the wind’s torque across two hulls so she does not heel, providing a stable and comfortable living platform in even the most terrific of winds. And her hulls are lean and narrow, so she does not pound into the waves. She slices through them with what can only be described as grace. The contrast in oceangoing comfort between the modern sloop and the Hokule’a is like that on land between a truck and a Cadillac.

There are other advantages as well. Our navigators steer the canoe by the rising and setting stars and find their latitude by measuring a star’s altitude with their hands, or observing pairs of stars whirling together across the meridian over the north or south celestial poles. The open deck of the canoe, uncluttered by superstructure, permits clear sightlines all around — an open-air observatory. Her twin hulls also provide an opportunity for her crew to deploy other subtle human senses to determine direction at sea. Hokule’a invites her crew to dance and she dances one way if she’s encountering swells from forward and another way in swells from abeam. Her motion differs if she’s running with the wind or sailing into it. The possible combinations are infinite, so the choreography is complex. Hokule’a demands attention from her human partners. If they falter, she reminds them. If they turn off course and into the wind she slows and shakes her sails. “Listen to me,” she says, “Can you hear it?” An alert helmsman knows to push the canoe’s steering paddle down to help her fall off. If the helmsman turns downwind she speeds up and pulls at her tiller. “Pay attention,” she says. All these are clues to maintaining a steady course, an important task for any navigator but particularly so for one finding his way without instruments. Determining longitude depends on dead reckoning, and dead reckoning, in turn, depends on keeping track of your course.

Catamarans are considered a recent innovation inspired by racing sailors seeking speed. But in Polynesia, such craft were invented thousands of years ago. Limited by stone and shell tools and the lack of iron fastenings, Polynesians could not fashion large European style plank-on-frame ships. Small outrigger canoes would not be seaworthy for long voyages, nor could they carry the cargo and people necessary to settle new islands. Large outrigger canoes would be unwieldy. So someone, thousands of years ago, thought of bridging two canoes with a solid deck. An advanced sailing craft was born out of necessity confronting the limits of a primitive technology.

Part three of a series. To learn more about Hokule’a and her voyage around the world, visit hokulea.com. To learn more about her visit to Martha’s Vineyard you may contact Sam Low at samfilm2@gmail.com.

Comments (7)

Comments

Comment policy »