A gripping documentary about the heroin epidemic on Cape Cod has focused new attention on the power of addiction, and the unprecedented toll it takes on addicts, their families and their communities.

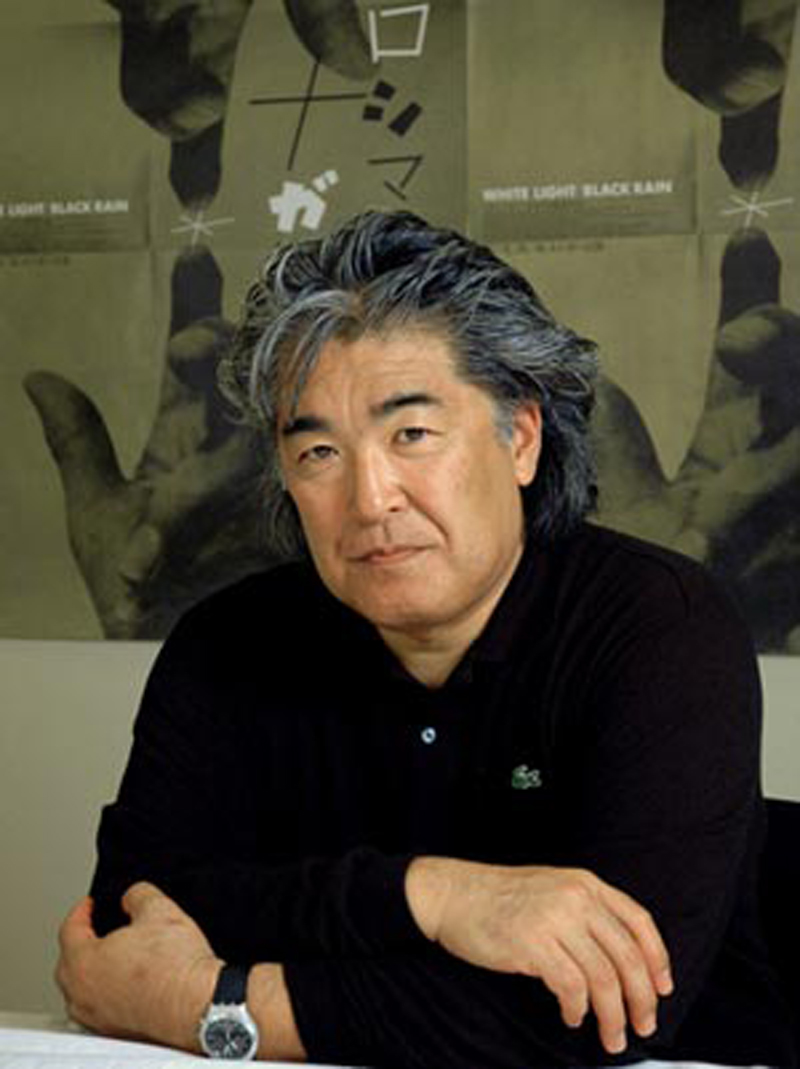

Heroin: Cape Cod, USA produced by HBO and directed by Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker Steven Okazaki, follows eight young people from the Cape through the desperate world of addiction. Mr. Okazaki and his film crews were able to get extraordinarily close to their subjects, all in their 20s. They talk openly about their singular quest for heroin, and the money needed to buy it.

The film is graphic, with scenes of the addicts cooking heroin in dirty spoons, shooting it into their veins with hypodermic needles, traveling to Boston neighborhoods where drug connections go awry, and mumbling their way through the stupor of an opiate haze. And yet the subjects are also frightening in their normalcy: a high school athletic star, a college student who achieved high honors in school, a young mother taking care of two adorable children. The documentary illustrates, in the stark glare of real life, the grip of addiction.

“Every time I shot up, it was like Christmas morning,” said 23-year-old Arianna in the film, describing her early use of heroin. The next scene shows her drawing heroin into a syringe.

“I don’t want to associate with anyone,” said Marissa, also 23, filmed applying a tourniquet to her arm and tapping her veins. “I just want to be with my heroin, with my needle.”

Both young women died of drug overdoses before the film was released.

Mr. Okazaki made a documentary about heroin addiction in San Francisco two decades ago. He decided to return to the subject after researching the dramatic increase in drug overdose deaths from opiate addiction, which most often begins through abuse of prescription narcotic pain medications. In Massachusetts, opiate overdose deaths more than tripled from 2000 to 2014 according to the Massachusetts Department of Health. In 2014, the last full year statistics are available, an estimated 1,173 people fatally overdosed.

“Twenty years ago, it seemed terrible,” Mr. Okazaki said in a phone interview with the Gazette. “In the whole state [California] the number of overdose deaths was well under 100, and people thought that was bad. It’s astounding how bad it is in New England, particularly on Cape Cod.”

The filmmaker explored making the documentary in New Hampshire and Vermont, but settled on Cape Cod because he found parents and addicts more willing to talk about the epidemic. One addict interviewed on Martha’s Vineyard was not part of the film. She had agreed to participate, but a parent objected, according to Mr. Okazaki.

In an initial meeting with parents in a Bourne support group who agreed to appear on camera, the crew hoped 10 people would participate. They ran out of chairs after more than 25 people showed up.

“Our role as a parent is to take care of our children,” said one parent in the film. “With this disease, we can’t.”

Mr. Okazaki said most of the addicts agreed to appear in the film in the hope that others could avoid addiction.

“I’m very clear, there’s nothing you necessarily gain from this,” he said, describing his approach to the film’s subjects. “Maybe it will be an interesting experience to be part of the process. If anything, you’ll help one other kid. When we said that, people came with it. [They said] I have no faith in my kicking this or getting better, but if someone else can see this and not follow my path, I’ll do it.”

Mr. Okazaki said the film crews were careful to avoid any ethical dilemmas while shooting the documentary.

“We don’t facilitate them getting drugs,” he said. “The addict’s life is pretty straightforward. We don’t encourage, we just shoot.”

The film crews did not observe any overdoses while making the documentary. They carried naloxone with them, a drug sometimes known by the brand name Narcan, which can reverse the effects of a heroin overdose.

The first screening of the film on Cape Cod included many of the parents in that initial support group. Mr. Okazaki said the response was mostly positive, though one parent walked out after seeing her son using heroin in the film.

“I’m really impressed with the community,” Mr. Okazaki said. “People own up to it. People know it’s not an unreal, exploitative view of the community. It is graphic and it is painful, especially losing the two girls.”

Edgartown police detective Michael Snowden, who saw the film shortly after it was released on HBO, said the film presented a real picture of a world few people see.

“It’s definitely an eye-opener to a lot of people that don’t think the Cape and Islands have a heroin problem,” he said. “The people in the documentary were pretty similar to the type of people we deal with day to day.”

Dr. Charles Silberstein, who treats many recovering addicts on Martha’s Vineyard, said the film was the subject of much discussion in his support groups.

“It’s interesting, the reaction from people who have lived that life,” Dr. Silberstein said. “Many of them said they find it triggering. It’s unbelievable, it looks so terrible, people die. Yet it brings back feelings of wanting to use. That’s the nature of addiction.”

Mr. Okazaki said he approached the documentary hoping to humanize his subjects in part to counteract the oversimplified view of addiction that many people hold, including the perception that young people are to blame for choosing a life of addiction.

“There’s just an inherent drama in this kind of situation,” he said. “When you’re 14, you make huge mistakes. Kids are disconnected, depressed. It’s when their relationships with their parents are at their worst. It’s not the same decision as an 18-year-old deciding to try this. It’s not the same as an intelligent 30-year-old saying I think I’ll try this. It’s not the same at all.”

Mr. Okazaki screened the film for Gov. Charlie Baker, the U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, and the White house drug czar Michael Botticelli, among many others, before its general release on Dec. 28 of last year. The movie will be screened on the Island at the Martha’s Vineyard Film Festival in late March.

“I just want to make it as relatable as possible,” Mr. Okazaki said. “That’s all I hope for, so people talk about it, sort of take away that excuse that it will never happen to me, that they have some acknowledgement that it could happen to someone close to me.”

Comments (37)

Comments

Comment policy »