Abel’s Hill cemetery is a place where people who like to keep tabs on their neighbors can do just that — for eternity, as they rest among them. From the gravestones off South Road in Chilmark you can hear the hum of cars speeding down-Island to the grocery store or up for a day at the beach. From the plot nearest the road, on tiptoe, you can just see who is in those cars. It’s a quiet cemetery, but graceful. The stories of its inhabitants — Pooles, Allens and Mayhews, war veterans, John Belushi and the unknown lying under unmarked stones — are sad and heroic, uneventful and romantic. To walk among the graves is to walk through history.

On an early October day, with the first chill of fall in the air, the man who knows the history best, 83-year-old cemetery superintendent Basil Welch, walked and talked.

“That’s Lillian Hellman’s grave,” he said, pointing down to a gray stone marked with a quill. “She didn’t own land in Chilmark, so someone else had to make room on their plot for her. Because you know, you can only be buried here if you own here.”

The late afternoon sun left a golden smudge atop the gravestones and on tree branches extending out toward the road. As he meandered, apologizing, his joints are not what they used to be, Mr. Welch told the tales he knew, his favorite bits of Chilmark history.

He pointed to the oldest stones and paused to wonder aloud why the lichen on gray stones grows green while the lichen on the white stones grows orange. He has asked many people, he said, but has never gotten the answer. He stopped at the gravestone of Benjamin Skiffe and knelt down to brush the dirt away — 1717. The grave is the oldest marked grave in the graveyard.

Mr. Welch is the man who keeps the cemetery in order; that is his job. He mows the grass and keeps the branches of trees from crowding the narrow dirt roads which wind among the plots. But he does more than that. He helps make sure the dead are remembered and honored. He puts flags out every Memorial Day and covers the tops of old graves with little hats so water does not fill their cracks. On the day of a burial, he gets to the cemetery before the family. He waits in the tool shed — he calls it the club house — and after everyone leaves, he comes out to cover up the hole. “Sometimes I find it sad,” he said of his job. “But sometimes the eulogies are so glowing.”

The Basset family of Chilmark gave the town the original plot of land for a cemetery, Mr. Welch said. There used to be a meeting house at the northeast corner. As carts and cars came to replace horses, and more people lived in the town, more died and more were buried, and the graveyard expanded.

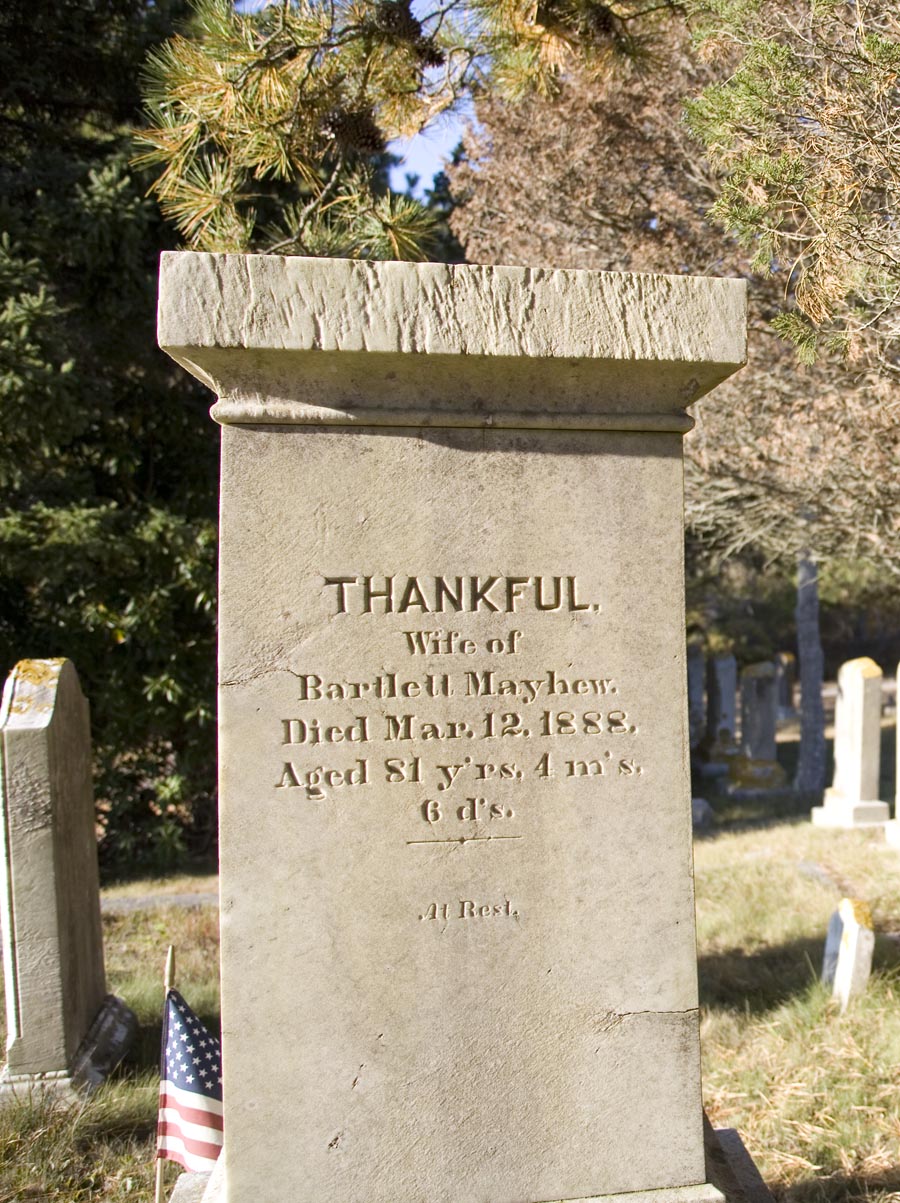

Many were buried in clusters. Among a cluster of Allens lie Sarah and Nathanial and Clarissa, Ebeneezer Allen, who died in 1733 and Eleazer, who followed in 1735. Rev. Experience Mayhew rests a few feet from Thankful Mayhew. “I don’t know when these names went out of style,” Mr. Welch said.

Mr. Welch assumed his post in 1985. He had retired from his job at the telephone company, but, only a few weeks into retirement, he began to go stir crazy. So he went to the cemetery commissioners, told them the cemetery was badly neglected and asked if he could tend to it.

“It’s quiet, peaceful and I’ll be here someday, so I figured why not,” he said.

“All these people I knew or worked with,” he reflected as he made his way into a newer section of the graveyard. He motioned to the stones of his sister and her husband, Marijane and Matthew Poole, and passed by the grave and bench marking Tony and Anne Fisher, who died in an airplane crash in 2003. “Those were nice people,” he said quietly.

He stopped at another spot and smiled. “In the 1940s, there was a plane crash in Vineyard Haven harbor,” he said. “Two people and I think the pilot were killed. I was a boy and I went down there and took pictures of it.” The two were from Europe, but had family on Island, the Weckmans of Chilmark. Their bodies were laid to rest there. Years passed and the property changed hands. Recently, it went on the market again, but the prospective buyer said he would not buy if the cremains remained. A relative of the original owner offered to move them to Abel’s Hill and there they lie today in the Weckman plot. “It’s interesting to me,” Mr. Welch said. “Because I took that photo and there they are now.”

With that, he pulled up the collar of his jacket. “It’s cold,” he said, and began making his way to his truck. But before getting too far, he paused and turned back.

“If you love someone, let them know,” he said. “You just let them know now, before it gets to this point.”

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »