A groundbreaking project to record the oral histories of 5,000 African Americans has returned to the Vineyard for the second time in its 17-year history, with more than three dozen videotaped interviews scheduled over two weeks.

“This project is really about discovery, and it’s about identity,” said Julieanna Richardson, founder and executive director of Chicago-based The HistoryMakers, a national archive now linked to the Library of Congress and 26 colleges and universities from coast to coast.

“Together we are doing what no one else in the history of the United States has done,” she said. And returning to the Vineyard, where The HistoryMakers first visited in the early 2000s, was a must, Ms. Richardson added.

In interviews, African Americans on Martha’s Vineyard display a sense of pride in their history, she said. “People talk about community a lot. We really want to be part of the Vineyard community.”

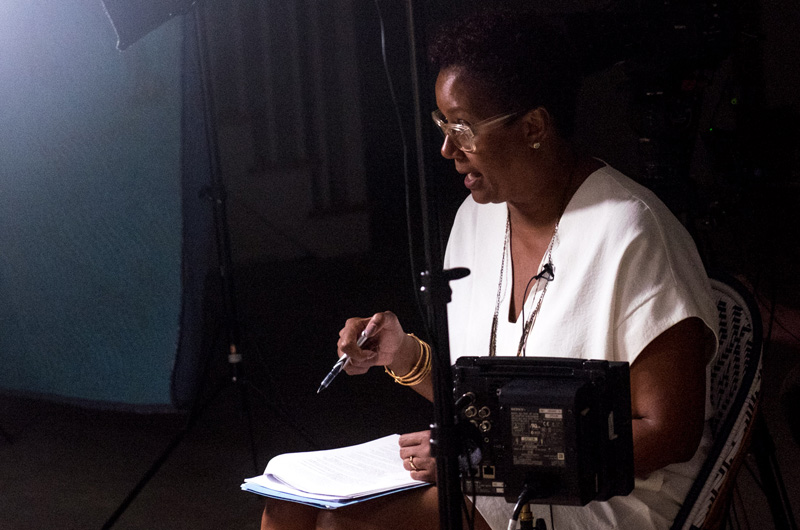

At the spacious West Chop home where Ms. Richardson and her team of archivists have been staying, a lower-level room provides the video studio (and people on the main floor are cautioned not to run the water while an interview is in progress). Wednesday afternoon, as The HistoryMakers’ Harriette Cole interviewed longtime Islander Skip Finley on video downstairs, Ms. Richardson took a chair in the great room to talk about the archive and how it came about.

At its most basic, the project seeks to fill in the gaps in black history that have existed since slavery was the law of the land. Ms. Richardson’s goal is to more than double the number of interviews — 2,300 — conducted with former slaves by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration from 1936 to 1938.

For the rest of the 20th century, those slavery narratives — housed at the Library of Congress — were the sole national archive of the black experience at first hand. As a nine-year-old schoolgirl in an overwhelmingly white Ohio town, “the only things we studied about black people were George Washington Carver and slavery,” Ms. Richardson recalled.

She had to wonder. “It was just hard to reconcile that he could have done all these things with peanuts when all we had been were slaves,” she said. These lessons left so many questions unanswered: What had happened before, and in between, and since? What was happening now?

The gaps in black history proved even wider the day her teacher asked the children about their family background, Ms. Richardson continued.

“Literally every hand went up,” with classmates naming all the European lands from which their ancestors hailed. Ms. Richardson put her hand up too — but after being black and Native American, she didn’t know what to say, or what her ethnic identity actually meant. Once again, she wondered: “What am I?”

It was an “empty feeling,” Ms. Richardson recalls, and it lasted for a decade — all the way to her sophomore year at Brandeis University, where she double-majored in theatre arts and American studies.

A research project on the Harlem Renaissance sent her to the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, where for the first time she heard a recording of I’m Just Wild About Harry, the popular song written in 1921 by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake for their boundary-shattering Broadway show Shuffle Along.

“The fact that a black songwriting team had written that song — that was like an ‘aha’ moment,” Ms. Richardson said. The empty feeling that had followed her since she was nine gave way to what she called a “euphoria of discovery,” which is still evident in the delight with which she talks about that eye-opening encounter.

Still, there were many years and multiple careers to go before The HistoryMakers was born. After Brandeis, Ms. Richardson attended Harvard Law School — “my father convinced me I could do anything with a law degree,” she said — and worked in corporate law after receiving her J.D. in 1980.

She went on to work for the city of Chicago as its chief cable administrator, a powerful position at a time when the city was actively franchising its cable network. Ms. Richardson later started her own cable television shopping channel, Shop Chicago, and followed that by founding a production company that managed several local cable channels for years.

And then — this is Chicago — she was “politically out,” Ms. Richardson said, her busy, eclectic and completely unplanned career at a standstill for the first time since law school.

“This was a hard time for me,” she told the Gazette. “I was very confused as to what my next step would be.”

But soon, a chance encounter with a panel discussion at the Memphis Civil Rights Museum would spark the idea that became The HistoryMakers 17 years ago.

“One of the panelists was Rev. Samuel Billy Kyles, who was on the balcony when Martin (Luther King Jr.) got shot,” Ms. Richardson recalled. Her next thought was, “People know Martin, but they don’t know these other people who were as important. And the name came to me at this time.

“I know what I want to do,” she recalls telling a friend. “It’s called The HistoryMakers and it’s an archive of black people.”

Ms. Richardson’s circle of friends was not convinced. In fact, some of them staged what she calls “an intervention, on a Saturday” to make sure she knew what she was talking about.

“Lots of people didn’t quite take me seriously back then — they’re telling me that now,” she said with a bubbling laugh. “I was as serious as a heart attack.”

Thanks to her cable TV ventures, she also had some seriously state-of-the-art videography equipment, which she put to use for the first interview — with radio executive Barry Mayo — in February, 2000.

Since then, The HistoryMakers has recorded 9,000 hours of testimony by African Americans from many walks of life, from stardom to obscurity. “We’re trying to balance the well-known with the unsung,” Ms. Richardson said: Whoopi Goldberg and Jessye Norman on one hand, for instance, and more than 200 top scientists on the other; a Tuskegee Airman and one of the less-renowned Golden 13, enlisted men who became the first African American commissioned and warranted officers in the U.S. Navy.

Interviews average three or four hours, with the longest at about 15 hours. That one is with the Rev. Jesse Jackson — “and he’s not done,” Ms. Richardson said. Barack Obama is in the archive, too, recorded as a young senator from Illinois.

About half of the interview subjects know a lot about their history, Ms. Richardson said, and the other half “know nothing at all.”

“I thought I would do it in five years,” Ms. Richardson said of her 5,000-interview goal. Seventeen years later, at a cost of about $1 million a year and still $12 million away from completion, she continues fund-raising through public television specials and local appearances such as the recent event Our History is Our Future, hosted by the Martha’s Vineyard Museum last Tuesday.

The evening program focused on the importance of preserving family history and lore as a legacy for generations to come. Panelists included Andrea Taylor, a former Boston-area journalist who is now the president and CEO of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute; Marilyn Dunn, executive director of the Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library in Cambridge and longtime Vineyard resident Elizabeth Rawlins, professor emerita of education at Simmons College. After-dinner entertainment was by jazz and R&B vocalist Vivian Male, who is one of the 37 people taking part in The HistoryMakers interviews on the Vineyard this month.

Ms. Richardson has not yet been interviewed for the archive. “I want to be 5,001,” she said.

Find out more at thehistorymakers.org.

Comments (6)

Comments

Comment policy »