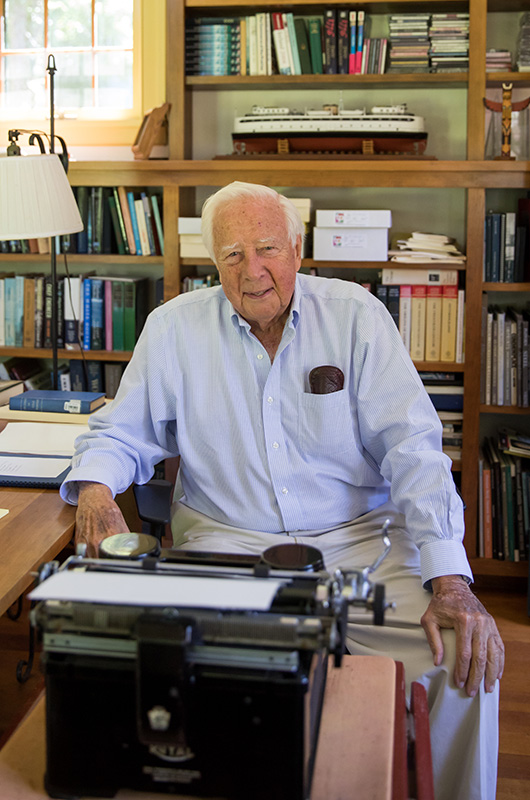

A man, 85 years old with far more than a century of stories to tell, walked toward a small shed behind his humble, white-shingled house on Music street. With steps slow but firm, he neared the barely five-by-ten structure tucked between the former Whiting farm, the Grange Hall and the West Tisbury Congregational Church. He reached the shed and opened the door. Although cleaned out for repairs, a desk left its imprint on the shed’s sun-soaked wooden floor. Gone too, for the moment, is the Royal Standard Typewriter he uses to tell his stories, a conveyance of history nearly as old as he.

The man had another story to tell.

“There are any number of ways to begin a book,” David McCullough said on the back porch of that very home in West Tisbury. “I like to begin with somebody on the move.”

In his most recent book, The Pioneers, the two-time Pulitzer Prize-winner and Presidential Medal of Freedom recipient who has chronicled the lives of two presidents, the pre-presidential travails of another, a pair of inventors, Americans in Paris and Europeans in America, as well as one mighty flood, one mighty canal, and one mighty bridge, begins this new story with a man few have ever heard of, going to a place few had ever gone before.

That man was Manasseh Cutler. His destination was the Ohio Country. And the first sentence of his story reads: “Never before, as he knew, had any of his countrymen set off to accomplish anything like what he had agreed to undertake — a mission that, should he succeed, could change the course of history in innumerable ways and to the long-lasting benefit of countless Americans.”

Not a bad way to start, even for the master himself.

“I always have loved beginnings,” Mr. McCullough said. “That’s what gets you off.”

This Fourth of July week, Mr. McCullough sat down to discuss his own beginnings, both in writing and outside of it, both on Martha’s Vineyard and off of it — and in particular, the beginning that led to his newest work.

The Pioneers tells the story of the earliest settlers in Ohio Country and their quest for survival. It details the passage of the Northwest Ordinance, an agreement that blocked slavery in a region as large as the 13 colonies and paved the way for the pursuit of the unalienable American rights of public education and freedom of religion. For a writer who has loved and lived in small towns like West Tisbury for much of his life, but had spent his career telling stories of great men and great achievements, it took a speaking gig at Ohio University’s Cutler Hall to discover the true small town story he’d been waiting a lifetime to tell.

“The chance, the absolute lucky strike chance of doing this book, happened because I got interested in Manasseh Cutler,” Mr. McCullough said. “And Manasseh Cutler, the man responsible for the Northwest Ordinance, which stopped slavery in an area that was just as big as the United States at the time, lived here and ran a chandlery in Edgartown. Can you believe that? Nobody knew who he was.”

In fact, for three years Mr. Cutler tried his luck selling nautical goods on the Vineyard at the height of Edgartown’s whaling years. His son Ephraim, who would go on to become the last vote to abolish slavery in Ohio, was born in Edgartown.

“The history of a location or community isn’t just what happened there,” Mr. McCullough said. “It’s about what the people who were from there happened to do elsewhere.”

Just like the Cutlers two centuries prior, Mr. McCullough then traveled down to Marietta, Ohio to research those Vineyarders who decided to make a life for themselves — and ultimately, for millions of other Americans — out west. What he found astounded him.

“The pieces numbered in the thousands,” Mr. McCullough said. “And then there were drawings and paintings and maps and artwork. Oh, and the artwork...it wouldn’t have been better off at Harvard or Yale, and not as well off in the Library of Congress...It was like finding King Tut’s tomb. And that alone was enough to make me want to get up in the morning for almost three years.”

As he got to know Mr. Cutler, Mr. McCullough realized the two had more in common than he ever could have imagined. Along with the Vineyard connection, Mr. Cutler had attended Yale, Mr. McCullough’s alma mater, and had traveled through Pittsburgh, Mr. McCullough’s hometown.

Mr. McCullough’s wife Rosalee told him he had to write the book. It was in the stars.

And three years later, he had.

“I realized I’ve been writing about people my whole life who set out to do something worthy, against all odds, and against innumerable adversities that they could not have foreseen, and still succeeded,” Mr. McCullough said. “And this is exactly about that.”

Unlike Manasseh Cutler, however, Mr. McCullough came from Pittsburgh to Martha’s Vineyard, and not the other way around. Just as it was Rosalee who told him he had to write the book, it was Rosalee who brought him to the Island over a half-century ago. He had just graduated high school, with the whole world and one beautiful girl waiting in front of him.

“I danced with her, and she was one of the best dancers I’d ever danced with in my life,” Mr. McCullough said. “And as time passed, I really became quite fond of her, and asked her where she went in the summertime. And she said her family had always gone to Martha’s Vineyard. Now, at that stage in life, the most important thing is to be cool. So I said, ‘oh yeah, oh yeah.’”

“I had no idea what she was talking about.”

He went home that night and broke out the atlas, only to discover Martha’s Vineyard was an island off the eastern shore of Massachusetts. He didn’t look back.

“That was the summer of 1951,” Mr. McCullough said. “I suppose I’d heard a seagull, but I don’t think I’d ever seen a stone wall before....I fell in love with the girl. But I also fell in love with the Island.” In the 68 years since, Mr. McCullough has written half his books — Adams, Truman, The Path Between the Seas, Mornings on Horseback and 1776 — on the Vineyard, with all the writing occurring in his small shed out back, and all the writing, always, coming on a typewriter. “When I was setting out to write my first book, I thought, ‘This is going to be business, McCullough. You ought to have one of these at home.’ So I went to a used office supply shop in White Plains and bought a Royal Standard Typewriter that was 25 years old. I spent I think 25 dollars for it. And everything that I’ve ever written, I’ve written on that typewriter; 575,000 miles on that one. But nothing ever went wrong with it...and after a while, I began to think, maybe it’s writing the books. So I didn’t dare switch.”

For an aspiring writer, there’s no better place in the world than a rocking chair on Mr. McCullough’s back porch. And for a reporter, there is no easier man to interview. Some subjects need to be asked a question before they get going. Mr. McCullough — similar to his own subjects — likes to begin on the move. While there are pauses, often intentional, between the paragraphs of speech that remain as elegant and articulate as his pages in print, the octogenarian never misses a beat. He is a modern Montaigne, spinning yarns both witty and wise on education (it’s declining) and on vocabularies (they’re declining) and on the practice of history itself — a subject he feels, more than anything, should encourage two values essential to the American ideal: empathy and gratitude. Both values, he believes, are also in decline but cannot be lost.

In The Pioneers, frontiersman and builder Joseph Barker raises his children, “to be useful, to be pleasant with [their] playmates, to be respectful to superiors, just to all, black or white, good to the poor, not showing pride or selfishness but kindness and good will...and to see to it that we looked to our own, more than to other’s faults.”

Over a century later, Mr. McCullough said it is paramount to remember those values as we grow up and grow old in the 21st century, especially in the context of the current immigration debate.

“Most of us were raised with these principles, and we can’t take those principles for granted,” Mr. McCullough said. “And we can’t let this horse’s ass who’s in the executive office set us so off course that we never get back. We can’t do that. But to say that he’s a horse’s ass is like saying that water’s wet. Or that fire burns.”

Mr. McCullough turns 86 on July 7. It’s fitting that a man who has chronicled so much of America happens to share its birthday week. While he doesn’t know what he will work on next, he does plan for there to be a next. This is an 85-year-old, after all, who still likes beginnings.

“I love my work,” Mr. McCullough said. “I don’t play golf. I don’t play tennis. I don’t have a sailboat, although I’d like one. And my friends ask, what do you do? And they laugh and I tell them, I work.”

Comments (22)

Comments

Comment policy »