Jonathan Scott is an optimist. Just off the coast of Noman’s Land is a rock that once rested on the island. At its base are a set of characters some think are Viking runes, slashes carved into the rock 1,000 years ago that essentially say Leif Eriksson was here. Others claim the characters are a hoax created by fishermen in the 20th century.

“I’d say there’s an 80 per cent chance they are a hoax,” Mr. Scott said in a recent interview outside his home in Chilmark. “But it’s the other 20 per cent chance that interested me.”

Mr. Scott’s journey to prove, or at the very least propose, that Vikings did indeed set foot on Noman’s Land and the Vineyard began as many quests do — seated on the Squid Row bench in Menemsha.

“A couple of years ago, we were sitting there looking around and musing as you do, when we began talking about whether the Vikings had spent time on the Vineyard.”

If Viking legends sound like an odd topic for a morning coffee klatch Mr. Scott quickly dispelled the notion.

“Oh, they talk about all kinds of things on that bench,” he said.

He went home and mentioned it to his wife, Marie Scott, whose family has roots on the Vineyard going back several generations.

“She said, ‘Oh sure, everyone talks about the Vikings being here.’ And so I thought I’m going to find out. It was an exploration.”

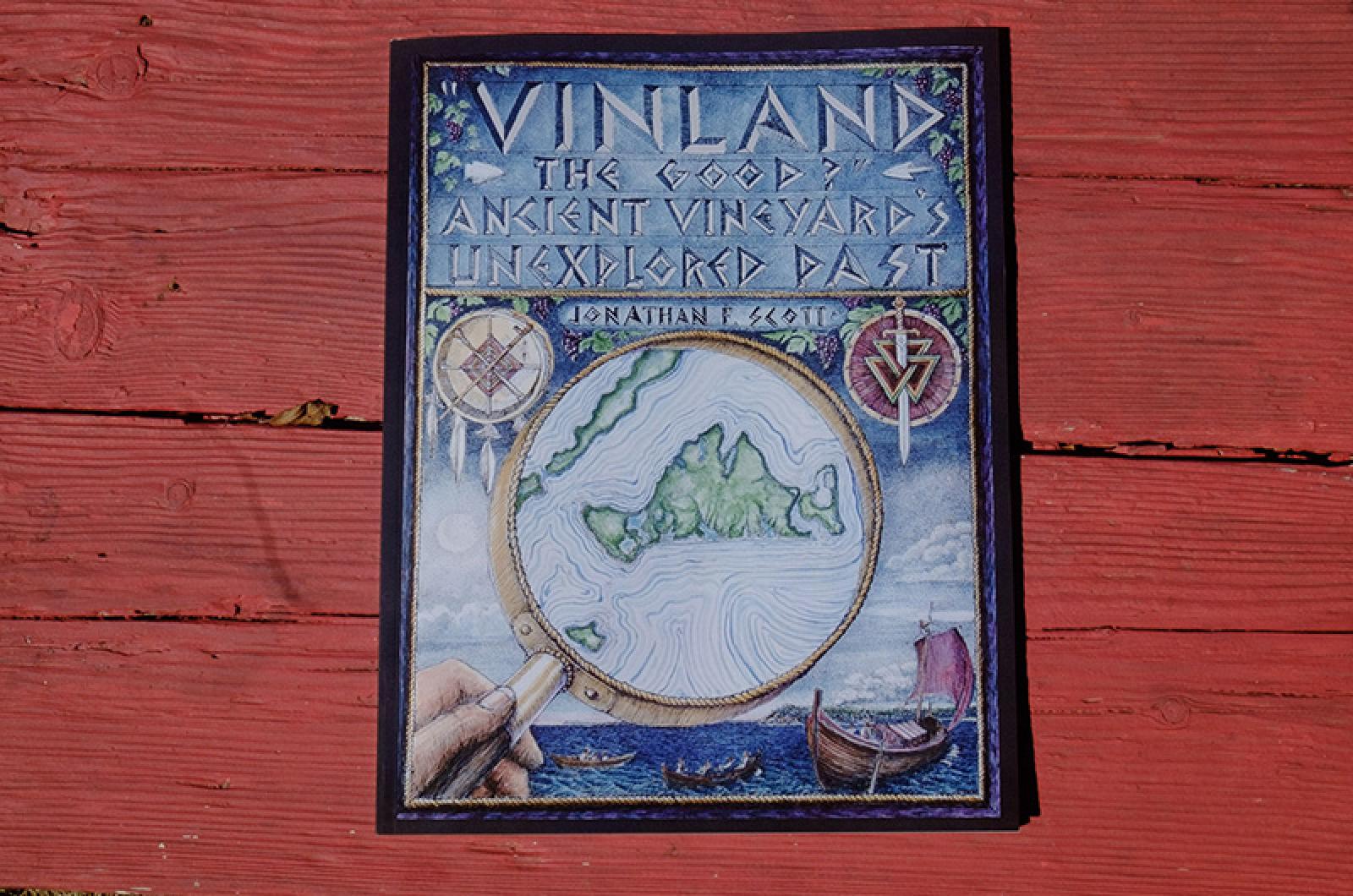

The result of this exploration is Mr. Scott’s new book, Vinland the Good, Ancient Vineyard’s Unexplored Past.

Mr. Scott is a mostly retired professor of art and architectural history at Castleton College in Vermont. He still teaches a course there each year, dividing his time between winters in Vermont and summers on the Vineyard, as he has done for decades. As a boy he lived on the Vineyard full-time for several years when his father, Henry Scott, was stationed at the naval base on the Vineyard and Noman’s Land.

“He was a professor at Amherst College but when he came back from his 25th college reunion at Harvard he announced that he had just joined the Navy, as everyone else had for World War II. But he had four young kids at home,” he recalled.

Mr. Scott’s father did his basic training in Oklahoma and then the family was sent to Corpus Christi, Tex.

“Which we all hated. It was hot, it was humid, the cockroaches were big as dogs. He asked for a transfer and was sent to Martha’s Vineyard where there were convoys just off the coast that were being ambushed by U-boats,” the author said.

Mr. Scott’s father had been trained in ship and plane recognition, and navigation.

“He was the guy who told the pilots what their mission was,” he said. “He was put in charge of the crash boat on the Vineyard to race out and try to save the pilots after they went down. And he was put in charge of Noman’s too because that is where the bombing range was.”

One of Henry Scott’s maps of Noman’s is featured in the book, the illustration marking not only the Viking rune stone but the possible location of Leif Eriksson’s house. When Jonathan Scott began his quest he didn’t realize he might be retracing his father’s footsteps.

“Apparently he was interested in Leif Eriksson, too. I wish I could have talked to him about it.”

As a guide for the book, Mr. Scott chose the historian Edward Gray who translated the ancient Viking oral sagas, both the Icelandic and Greenland ones, in his book Leif Eriksson, Discoverer of America A.D. 1003, published in 1930. He also spent time with Charles Banks’s indispensable History of Martha’s Vineyard. Both books, he said, provide ample evidence that the ancient land called Vinland by the Vikings, which many presume to be in Newfoundland or Maine or even Rhode Island, was indeed Martha’s Vineyard.

“The more I looked into it the more everything fit with the sagas,” he said. “It’s extraordinary if you know the geography of this general area, including the Cape, you could read the sagas and think, oh my god, yes it all fits.”

He was referring to the sagas recounting of the Viking’s journey from Greenland and Iceland to North America, then heading south to a place of expansive white, sandy beaches they called “wonder strands,” to a north-pointing cape, a sound filled with sandbars, and a tidal river that leads into a lake, which Mr. Scott thinks could have been Menemsha Pond which in those days was not much more than a tidal creek only navigable during high tide.

This is where the sagas say Vikings ran aground and eventually came ashore, first during Leif Eriksson’s expedition, then followed by his brother Thorvald and eventually his younger sister Freydis, a misanthropic sort who in a rage that would have made Shakespeare proud led a slaughter of her family members and countrymen, all done in the quiet hamlet of Chilmark.

In Mr. Scott’s eyes the pieces continued to fall in place, from the sagas description of the land and water around the Vineyard to his son’s discovery of a potential Viking mooring stone in Stonewall Pond.

The book is illustrated by local artist Laurie Miller, a longtime friend of the author. Mr. Miller’s detailed renderings breathe life into maps, Freydis’s massacre and the flora and fauna of long ago.

The book was designed by Janet Holladay at the Tisbury Printer.

Mr. Scott is quick to point out that his book is just an exploration, led by his own curiosity and not based on scientific fact. No conclusive artifacts have been found on the Vineyard and there are many competing stories out there. But navigating the breadcrumbs of a possible Vineyard past continually surprised and delighted him.

“If we have a really good case, then this is a part of Vineyard history,” he said. “That’s why I call it the Vineyard’s undiscovered past.”

Vinland the Good is available for sale at the Bunch of Grapes Bookstore, the Martha’s Vineyard Museum and Fo’c’sle Locker in Menemsha.

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »