The Brownsville Texas Incident of 1906: The True and Tragic Story of a Black Battalion’s Wrongful Disgrace and Ultimate Redemption, by Lieutenant Colonel William Baker. Red Engine Press, 2020, 504 pgs., $24.95

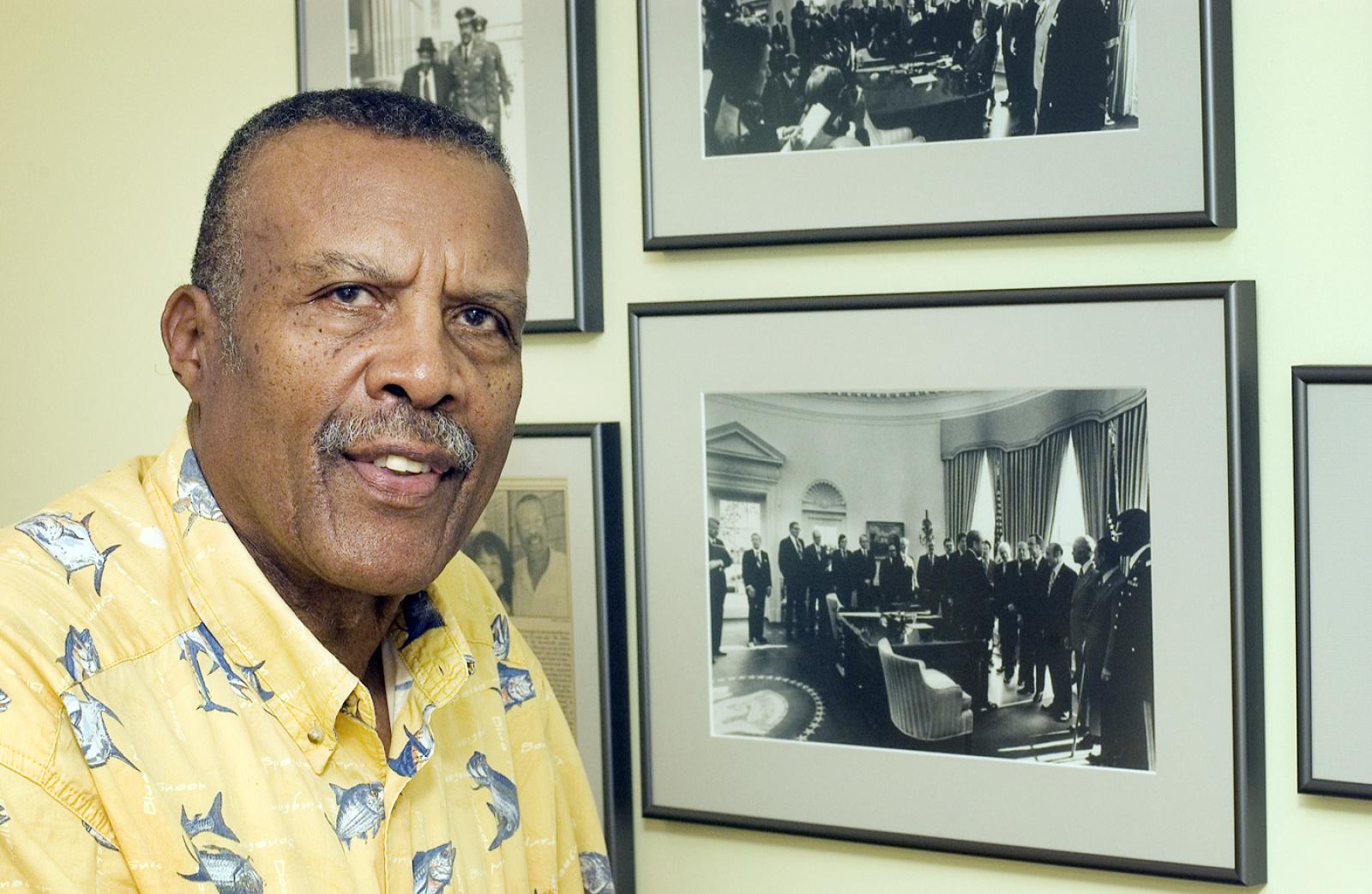

Lieut. Col. William Baker died in October 2018. It would take two more years for the seasonal resident of Oak Bluff’s masterwork to be published posthumously, thanks to the efforts of his wife Bettye Baker.

The event at the center of Mr. Baker’s book The Brownsville Texas Incident of 1906 happened at midnight. On August 13, 1906, a wave of violence swept through the town of Brownsville, Tex. Windows were broken, property was damaged and destroyed, and a spray of gunfire not only wounded a policeman but killed a bartender. The shooting lasted less than a quarter of an hour, but it left a deep mark of carnage in its wake.

The townspeople had been traumatized, and they didn’t have any trouble assigning blame, because unrest had been festering in Brownsville for months, ever since the town learned that the War Department was going to replace the all-white battalion at the town’s Fort Brown with the all-black First Battalion, 25th Infantry Foote US Army, composed of 167 black men.

The town’s mayor, Dr. Frederick Combe, knew that President Theodore Roosevelt’s Secretary of War, William Howard Taft, had received many complaints about this choice — and some threats of what might happen if those complaints were ignored.

Taft eventually responded with his typical combination of logic and optimistic cluelessness, assuring Brownsville that “Sometimes communities that objected to the coming of colored soldiers have entirely changed their view and commended their good behavior to the War Department.”

Taft’s boss reacted with far less enlightenment after the incident. Roosevelt imagined a “conspiracy of silence” among the First Battalion and held all 167 of them responsible for the violence. He discharged them without honor and without trial, stripping them of their pensions, banishing them from government work, and laying on them a weight of disgrace that would mark the former members of the battalion forever.

“It followed almost all of them into old age,” Mr. Baker writes. “It drove some into insanity. And cruelly, it followed most of them to their deaths. Along the way, as they wandered across the country, they told stories of their innocence to anyone who would listen.”

Mr. Baker came to the Office of Equal Opportunity at the Pentagon in 1972, and he did deep and unprecedented research into the Brownsville incident, presenting a case to the Department of the Army that resulted not only in the reversal of Roosevelt’s decision and the exoneration of the First Battalion but also compensation to the one surviving member of the unit.

Mr. Baker’s work did what the work of scarcely any historian ever does: it changed history. And in The Brownsville Texas Incident of 1906, he transforms that research into a narrative of gripping power and chilling relevance in the age of Black Lives Matter.

The book often makes for disturbing reading, obviously. In order to fully flesh out the long ordeal of the First Battalion members, Mr. Baker takes readers deep into the world of early-20th century racism. And although large swaths of the story have depressingly precise echoes in our own era, Mr. Baker is careful to bend the arc of his story in some positive directions, culminating in an Oval Office ceremony in 1973, with President Nixon granting thousands of dollars of compensation to any surviving Brownsville veterans and their widows. A few years later, in 1977, the last surviving Brownsville solider, Dorsie Willis, died at the age of 91.

“A lone bugler played taps,” Mr. Baker writes. “The honor guard fired the gun salute and Dorsie Willis, honorably discharged US Army veteran, formerly Company D, Brownsville station, was finally at rest.”

Mr. Baker investigates every aspect of the incident, and he makes the valuable decision to make his own investigations a large part of his narrative. This book is not only the definitive account of the Brownsville Incident — a long-needed corrective to the standard versions of this old story — but also a completely fascinating look inside the historian’s craft, a very effective dramatization of how researchers go about sorting reliable information from the mass of random historical records.

He also makes the slightly more controversial decision to let those records actually speak directly to the reader. Throughout the book, we get tense, dramatic exchanges like this one between Inspector General of the Army Earnest Garlington and a hapless sergeant merely trying to tell the truth: “All the men deny it [the sergeant said]. I’m convinced that no man in the 25th Infantry did this. Sir, I believe that they don’t know anything to tell you. That’s why they’re not telling.”

Mr. Garlington pounded the table with his fist. “You’re a liar. You are lying, sergeant!”

The Brownsville Texas Incident of 1906 would be an important book even if it were just Mr. Baker’s account of a wretched mark in U.S. history. But because Mr. Baker himself was precisely the right man at precisely the right time, the book is doubly valuable. It not only tells the story true, but it literally sets the record straight.

Comments (14)

Comments

Comment policy »