Imagine a drive across the country in the days before President Eisenhower built the interstate highways. Options were limited. Country roads and main streets spider-webbed haphazardly across the countryside, connecting train stops and family farms and general stores.

An alternative was the Lincoln Highway — a two-lane road connecting Times Square to San Francisco, built in 1913 and conceived by American entrepreneur Carl Fisher — which now gives its name to Amor Towles’ third and most recent novel.

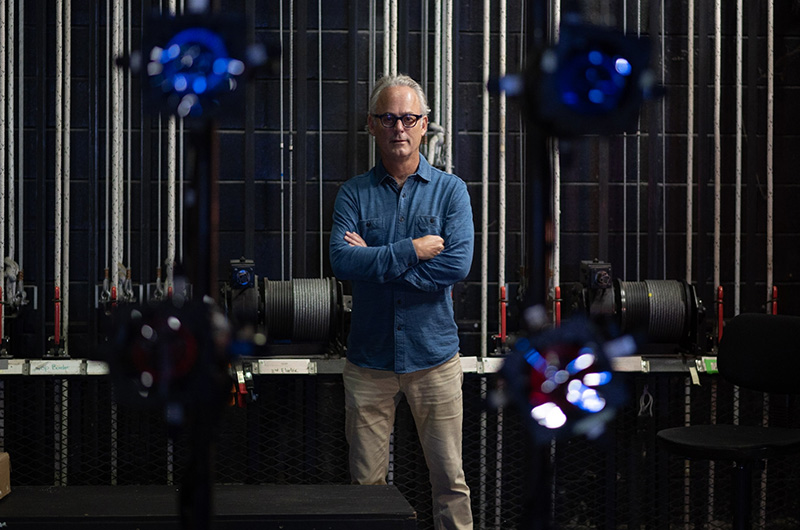

Mr. Towles spoke on Sunday at the Performing Arts Center as part of Martha’s Vineyard Author Series. At the talk he described the history behind his novel The Lincoln Highway — and his approach to history when writing. Rather than walk the audience through his book, he focused on the Lincoln Highway itself, a feat of early 20th-century American infrastructure.

“What is it about Lincoln highway, the actual road that made it feel so perfect for me as a metaphor at the center of this narrative?” Mr. Towles asked the audience. He picked up a clicker and a portrait photograph appeared on the screen behind him. “Well, to understand that, we have to go back and start with this guy. Well, there he is. This is Carl Fisher, born in 1874.”

Mr. Towles’ three novels — Rules of Civility, A Gentleman in Moscow and The Lincoln Highway —have sold over six million copies across 30 languages. On Sunday, his presentation began by tracing Carl Fisher’s rise from humble Midwestern beginnings to the pinnacle of the early automotive industry (he pioneered one of the earliest functional headlights). In pseudo-retirement, he pushed for national highways, starting with the Lincoln Highway — which a young American officer, Dwight David Eisenhower, crossed as part of a national tour at the end of WWI.

For Mr. Towles, characters and story take center stage, even where history is involved.

“My book is a novel, you know, it’s not a work of history,” Mr. Towles said. “And so appropriately at its center, at its heart, are individuals. And in particular, in this story, it is a group of 18 year old or 19 year old young people… who are at that moment in time where they’re beginning to understand that they have the liberty and the responsibility of deciding their lives for themselves.”

Mr. Towles suggested Sunday that it was from thematic interchange — between the freedom of youth and the freedom of the open road — that he chose The Lincoln Highway’s title.

Mr. Towles said that he doesn’t consider himself a historical novelist, despite what reviewers and readers might say. While he enjoys diving into the history outside the text, he’d rather the novel stay grounded with the characters. He compared his own use of history to the set of a play, which might eschew perfect realism in favor of giving the audience a broad sense of time and place.

“If you think of history, for me, it is the painted backdrop,” Mr. Towles said. “And not only is it not designed to be perfectly like real life — in fact, I am specifically intending to do it in an impressionist style. Because what I wanted to do is to give you that sense of a moment in time, a little sense of space, a sense of mood.”

Sometimes the desire to evoke “a sense of mood” rather than relay every detail gets Mr. Towles in trouble, he admitted. He said that after each of his books gets published, he personally receives waves of corrections from his readers.

Mr. Towles read a series of more humorous corrections during his talk. One correction he received upon the publication of the Lincoln project focused on the city of Ames, Iowa. A character in the novel thinks he might rob a nearby liquor store. However, a dedicated fan informed Mr. Towles that, since her parents were heavy drinkers in Ames, Iowa in the 1950s, she knows that there were no liquor stores in the city.

Mr. Towles encouraged his audience to write to him, with corrections, questions and anything in between.

“If you want to share with me your parent’s drinking habits, you are free to do so,” he joked.

Comments

Comment policy »