Robert S. Douglas, renowned designer and captain of the topsail schooner Shenandoah — as well as a teacher and mentor and businessman who founded the Black Dog apparel company — died early Wednesday morning at the family’s home at Arrowhead Farm in West Tisbury.

He had turned 93 on March 18.

In the 56 years between the launch of Shenandoah in 1964 and her donation to an Island educational nonprofit in 2020, perhaps no other person in the United States owned and commanded a passenger-carrying sailing ship longer than Mr. Douglas. Certainly, no one parlayed the business of sailing into a trademark as widely recognized around the world as the Black Dog Tall Ships brand.

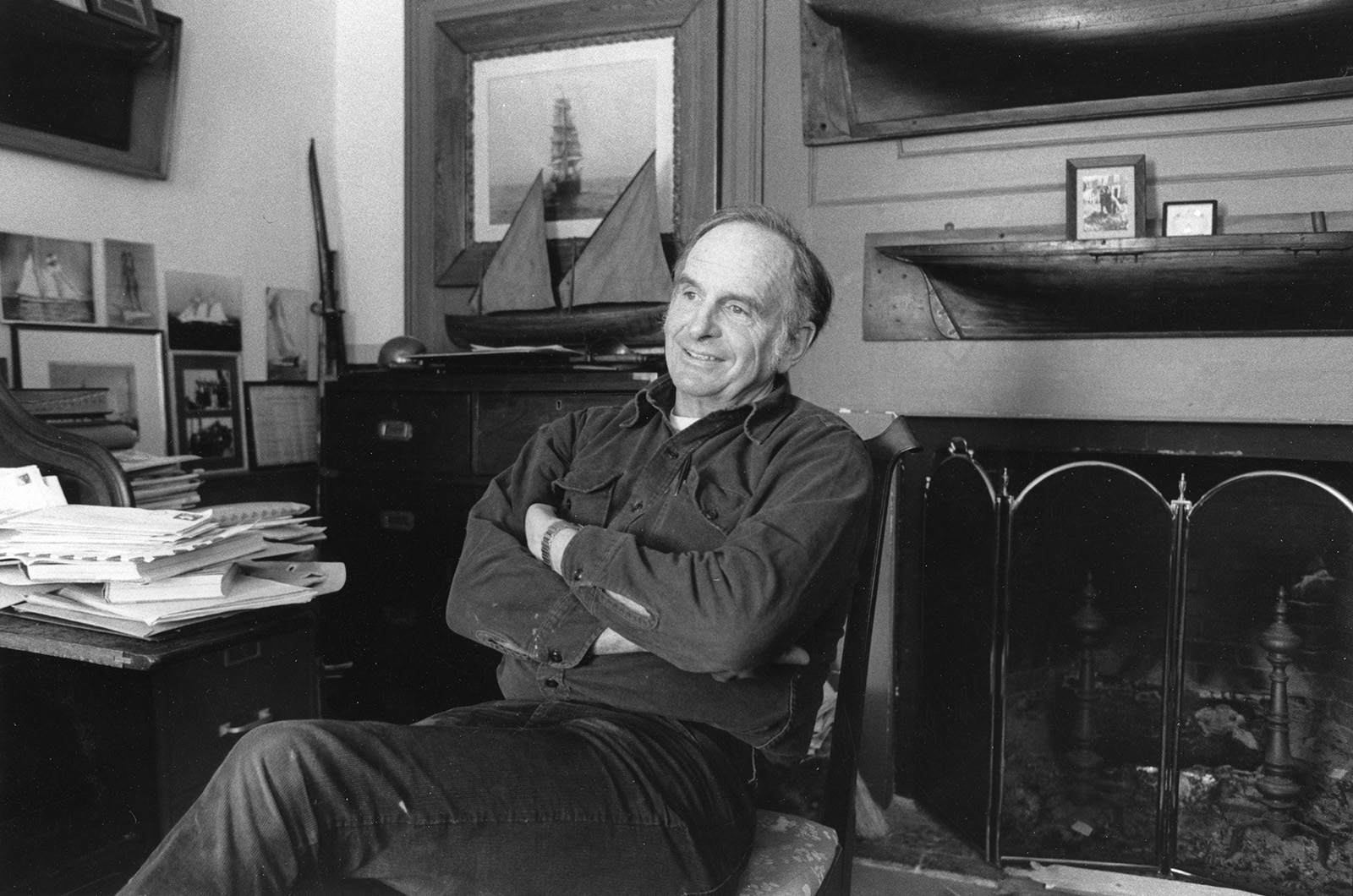

Tall and powerfully built, with sharp eyes and a strong jaw, his uniform generally consisted of a baseball cap, work shirt and rumpled trousers. Whether at the wheel of Shenandoah or leaning back at a table with family and friends at the Black Dog Tavern, which he built on the Vineyard Haven waterfront in 1971, one could tell from a distance that he was man of reserve, more given to watching and listening than to talking.

His voice was a low rumble, and some friends described Bob Douglas as shy. With that in mind, his accomplishments and legacies at sea and ashore appear all the more adventurous, public and lasting.

Born in Chicago on March 18, 1932, his ties to the Island and to Vineyard Haven began in 1947, when his father James H. Douglas Jr. and mother Grace Farwell Douglas of Chicago and Lake Forest, Ill., began renting a house at West Chop.

The senior Mr. Douglas served as secretary of the Air Force and deputy secretary of defense under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, among other posts in Washington, and worked in private life as a lawyer and businessman.

In boyhood Bob and his brothers James, John and David lived energetic summertime lives on the Island, and when asked to trace the events that led him to design, build and skipper Shenandoah, Captain Douglas always looked back to a moment on Vineyard Haven harbor.

In a 2004 interview with Martha’s Vineyard Magazine, he said that when he was about 20 he saw a Friendship sloop sail into the harbor, towing a sharp-ended Peapod dory “all painted up like the proverbial little red wagon: dark green hull, black waist, white guards.” He rowed over to find out where the owners had found it.

The sailors told Bob that Havilah (Buds) Hawkins of Sedgewick, Me., had built the skiff.

Subsequently, Bob not only commissioned one of his own, but also in the summer of 1960 signed on to sail with Captain Hawkins as mate aboard two 19th-century sailing vessels — the Stephen Taber and Alice S. Wentworth — that had shifted from the world of hauling freight to carrying passengers on cruises along the coast.

Mr. Douglas began to think about earning a living at the helm of a sailing ship, but felt he needed more experience before he took over an old vessel of his own or built one from the keel up. Beginning in November 1960, he served as a seaman aboard a replica of HMS Bounty, which had been built for a remake of Mutiny on the Bounty, starring Trevor Howard and Marlon Brando. He sailed with the new Bounty from Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, down the coastline, through the Panama Canal, across the Pacific and on to Tahiti, where he worked for three months as a sailor on the film.

On his return to New England, Mr. Douglas rejoined Buds Hawkins as the veteran captain began a new enterprise. From the Harvey Gamage shipyard in South Bristol, Me., Mr. Hawkins had commissioned Mary Day, the first windjammer to be built new for the cruising business in North America.

As Mr. Douglas ran errands and helped a bit with construction, he took note of a 19th-century revenue cutter in a book by Howard I. Chappelle. The sailing ship he saw in the Chappelle book was the revenue cutter Joe Lane, launched in 1849. He decided the Joe Lane was not only the sort of sailing ship he wanted to build, but that Gamage was the yard to build it.

Yet he also knew that the design of the Joe Lane, a vessel that chased down seagoing tax cheats and coastal pirates more than a hundred years before, was imperfectly suited to carry passengers in the present era. Although he had no formal training as a marine architect, Mr. Douglas redrafted her lines — raising her sides, making the hull more symmetrical from bow to stern — to conform to his modern day purposes.

The topsail schooner Shenandoah was launched Feb. 15, 1964, and sailed into Vineyard Haven on her maiden voyage on July 15. She measured 108 feet on deck, displaced 170 tons, and her two steeply raked masts rose 94 feet above the water. She carried square topsails and a gaff-rigged foresail and main.

Upon her arrival, the Vineyard Gazette wrote that the new vessel “symbolizes all that was beautiful, judicious and distinct in the sailing craft that made America famous on the seven seas.”

Shenandoah and the Mary Day were said to be the first two commercial sailing ships to be built in the United States without engines since 1921. Drawing from tradition, Mr. Douglas and Mr. Hawkins both felt that they could handle their boats perfectly well without them. When auxiliary power was needed around wharves or other tight places, Mr. Douglas used a small yawl boat with an engine to nudge his schooner here and there. Otherwise, wherever Shenandoah went, she sailed.

It has long been said that Mr. Douglas was so devoted to his vessel that only once in a career lasting more than five decades did he ever step into an auxiliary boat for a moment to see her sail himself.

Shenandoah began sailing out of Vineyard Haven as her homeport in 1964 adding a new, enduring color to the life of the harbor, and the schooner did her part to help keep the waterfront of Tisbury a place where a variety of people and enterprises thrive. Toward the end of his sailing career, Mr. Douglas figured that some 400 young adults had worked aboard Shenandoah either as deckhands or mates.

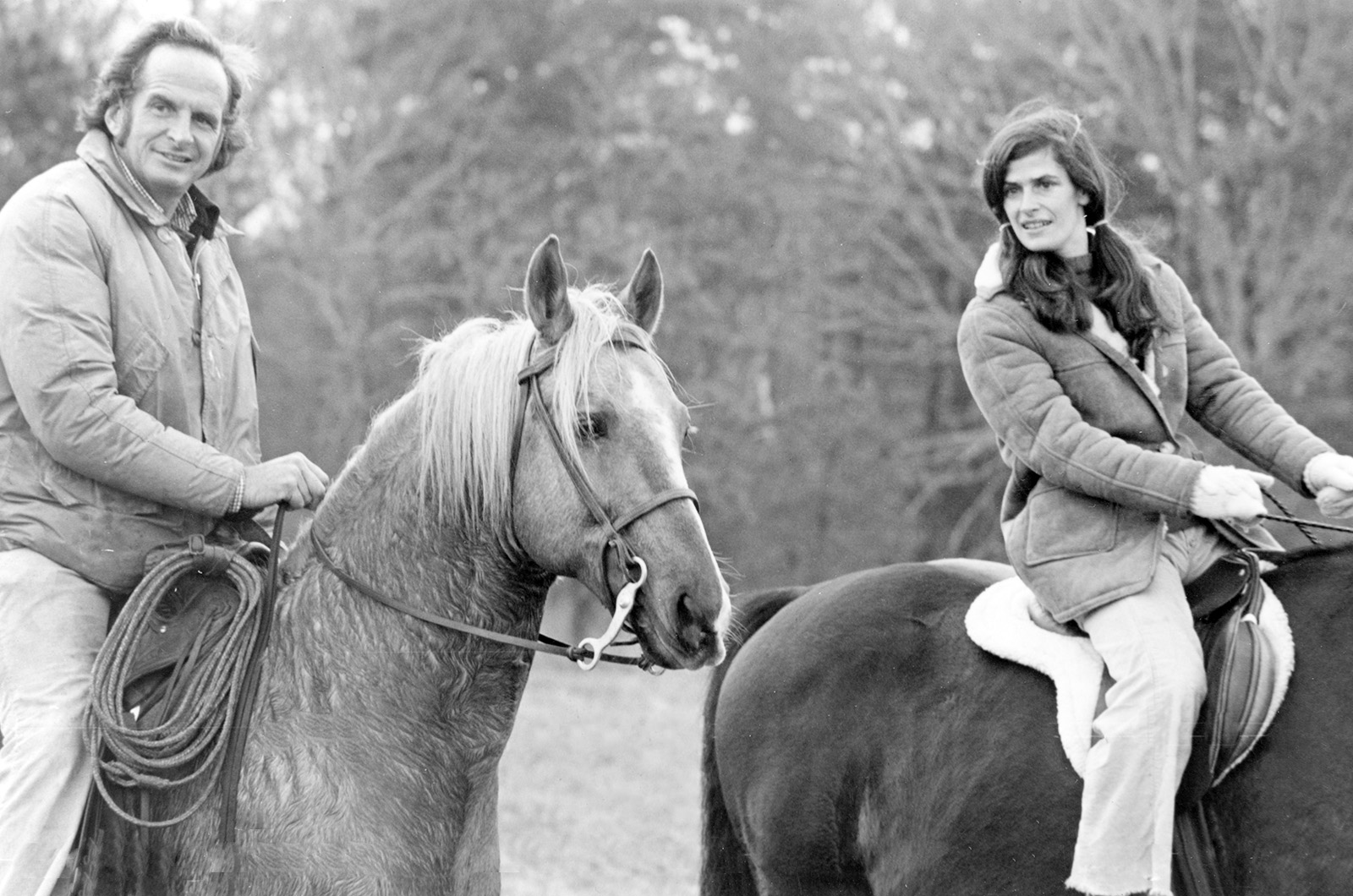

In 1970, Mr. Douglas married Charlene Lapointe, herself a sailor and a leader of the waterborne girl scout program known as the Mariner Scouts, who now runs Arrowhead Farm, where she boards horses and gives riding lessons to students of all ages. They have four sons — Rob, Jamie, Morgan and Brooke — and six grandchildren.

In 1993. Mr. Douglas began to change the mission of his schooner. He had come to believe that adults were too impatient to deal with the sort of cruising Shenandoah did, sailing wherever favorable winds and seas drew her.

“They want to know where they’re going to be and when they’re going to get there,” Mr. Douglas told the Gazette. “As human beings age, they tend to lose their resiliency.”

Instead, he began to take children on seven-day voyages at the start of the school year and on overnight trips during the summer. The youngsters played, learned and worked alongside the crew, sharing the duties and camaraderie of a 19th-century sailing ship brought forward into their own world.

In 2020, Mr. Douglas donated Shenandoah to a nonprofit group now known as the Martha’s Vineyard Ocean Academy, whose purpose is to help youngsters develop skills in the realms of environmental stewardship, mariner competency and personal development.

“I would strongly approve of bonsai-ing people right around 11,” he told the Vineyard Gazette in 2013. Youngsters that age are “just great big sponges, they can’t get enough. Everything is new and interesting. I provide the platform, a different lifestyle, one that is entirely different from anything they have ever experienced.”

It is now reckoned that more than 5,000 children have sailed aboard Shenandoah at least once.

The year Shenandoah arrived, Mr. Douglas also began to buy properties along the Vineyard Haven waterfront that today make up much of what was originally called the Coastwise Packet Company and is known now as Black Dog Tall Ships Inc.

Soon, Mr. Douglas added a building of his own.

Legend suggests that one day in 1969, Mr. Douglas began to sketch a gambrel tavern on napkins after he realized that there was no place in Vineyard Haven where one could buy three meals a day year-round. The mascot of the new tavern was a Labrador-boxer mix named Black Dog after a character in Treasure Island. Drawn by Stephanie Phelan, and incorporated into the business in 1976, it stood in profile, looking proud and expectant at the same time.

The mail order business began in the late 1980s when the company sent out a catalog of T-shirts, mugs, cookie tins and posters, all typed on a single sheet of paper. The simplicity and stateliness of the Black Dog imprint began to draw attention. The logo traveled the country on the backs and caps of residents and visitors. Famous people, including President Bill Clinton, were photographed wearing Black Dog gear.

The business took off in 1991 after Rolling Stone proclaimed the emblem cool and ran a photo of three attractive women wearing sunglasses and long-billed Black Dog caps.

“All hell broke loose,” said Elaine Sullivan, who was running the mail order operation then.

“The tail started wagging the dog,” Mr. Douglas told the Gazette in 1997. “It started as a restaurant and it turned into a dry goods business.”

The national and international growth of the Black Dog logo and brand was an impressive, even startling achievement, given the size of the place where it all began. But for Mr. Douglas what mattered most, beyond his family life, was sailing and the sea.

In 1967, Mr. Douglas purchased what would become the second flagship of the family fleet of sailing ships. Her name was Alabama, and she was built in 1926 to serve as a vessel housing pilots who helped crews navigate the ship channel at Mobile, Ala.

The man who drew her lines was Thomas F. McManus, renowned for his designs of Gloucester fishing schooners. Although built to be a schooner, Alabama, 90 feet long, was never given a sailing rig and had only engines. Until Mr. Douglas purchased her, she had spent most of her life riding at anchor off Mobile.

Mr. Douglas brought her to Vineyard Haven, and for the next 27 years Alabama lay moored next to Shenandoah, waiting for her chance to go back to work. In 1995, he sent her to Kelly’s shipyard at Fairhaven and began to restore her. As he had with Shenandoah three decades before, Mr. Douglas designed a schooner rig for the vessel.

He also hired Gary Maynard, a world sailor, builder and Island resident, to oversee the rebuilding and rigging of the schooner, a job that took two years. On August 30, 1997, Alabama, sailing for the first time in her life, departed Fairhaven and on her arrival at Vineyard Haven, Shenandoah greeted her with a 21-gun salute. Today Alabama sails on short cruises out of Vineyard Haven harbor.

Among other skills, Mr. Douglas was an evocative writer. In Sea History magazine in the winter of 1986-1987, he described the pleasure he took from his life cruising the southern New England coastline: “.... And there is one adage I have found to be true. The bigger the sailing vessel, the more fun it is to sail. Proportion and rig are contributing factors to the excitement a big vessel can produce: seven thousand square feet of canvas straining overhead, the roar and thunder of the lee bow wave, the view from aloft on the crosstrees seventy feet above the decks, the slow determined response of a one hundred and seventy ton hull to two or three spokes the wheel, the intricacies of square rig, sharply braced yards and tapering topmasts outlined against a star-filled sky.

“This whole sailing ship ethos is powerful and many faceted, but undeniable, and once involved with it, one is never quite the same again.”

He is survived by his wife, four sons and their families.

Funeral arrangements are incomplete.

Comments (40)

Comments

Comment policy »