Many contributors to black history weren’t black. Take the abolitionists, for example. It’s unknown when abolitionism became a practice on Martha’s Vineyard; although not universal it was widespread. Slavery ended in Massachusetts in 1783, long before the rest of America and for 30 years before the Emancipation Proclamation the Vineyard had a number of prominent right-doers.

Jeremiah Pease was one. He was a devout Methodist who traveled on horseback, in carriages and walked when necessary to minister to Island people. In 1835 Pease and his mentee Hebron Vincent acquired the land for the Camp Ground. From his diary at the MV Museum we know of his activities such as the Chappaquiddick funeral of Betsey Carter, “a pious coloured woman” (sic) in 1842. On August 9, 1847 Pease “Attended the funeral of Celia Johnson...it was a solemn time. A great number attended her funeral. She was esteemed a pious Godly woman for several years Past. It was affecting to behold her aged Mother taking her last look of her departed child, she being the only colored person now living in all the region of what is called Farm Neck, at which place a very large number of indians (sic) and coloured (sic) people formerly resided.”

Pease’s friend Hebron Vincent is called ‘the man who kept the records’ of the Camp Meeting Association. He was a self-educated teacher, minister, attorney, historian and community leader. The MV Museum has Hebron’s sixteen and a half page treatise, “A Vindication of the African Race” that speaks volumes in of itself.

Robert Morris Copeland designed what became the Cottage City Historic District in 1866 and supported women’s rights. Copeland ‘s attempt at developing a training site for a black regiment during the Civil War ended his career when he was dismissed for insubordination. Copeland recognized that women’s issues and slavery were human issues.

Ebenezer G. Lamson built a home in Eastville near his friend Ichabod Norton Luce. He was an abolitionist who, when the Civil War started, got a contract to produce 50,000 rifles for the Union Army. The precision instruments made by his firm, Lamson, Goodnow & Yale were used by other companies that manufactured half of the rifles, muskets, carbines, pistols and bayonets used in the war. In 1869, the company presented President Ulysses S. Grant (who visited Oak Bluffs five years later) with a 62-piece dinner set. Part of the set is on display at the Smithsonian Institute.

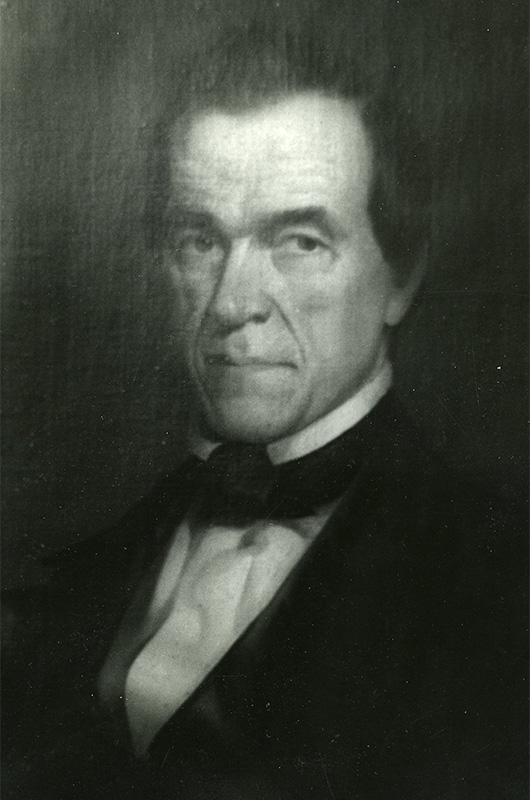

As a boy Ichabod Norton Luce joined the merchant marine and delivered materials to nearby ports. He had worked as a boat builder in Mattapoisett where he met and befriended Frederick Douglass and became a supporter of the abolitionist movement. After becoming a successful whaling captain Luce was elected president of the Lyceum in 1853. In 1858, as a Massachusetts State Senator representing Cape Cod and the islands, Luce led the effort of Oak Bluffs’ secession from Edgartown, and in 1880 was moderator of Cottage City’s first Town Meeting. The Vineyard Gazette’s Henry Beetle Hough wrote about Norton: “Abolitionist, boat builder, mariner, forty-niner, senator, keeper of the Gay Head Light, denouncer of speculative enterprises, divider of a town.”

Edward Dobbs Linton was a neighbor of Ichabod Luce and Ebenezer Lamson. Early in life, Linton went to New Bedford, apprenticed as a boat builder and also became acquainted with Frederick Douglass whose ideals he espoused as an editor of The Liberator, the abolitionist newspaper founded by William Garrison. Linton went on to become one of the founders of Edgartown’s Lyceum, where Frederick Douglass spoke.

Frederick Douglass, the abolitionist and former slave, spoke to Vineyard people about the nation’s values of freedom, Christianity and economic opportunity at Edgartown’s Town Hall on Saturday, Nov. 28, 1857 and the Federated Church (then the Congregational Church) the next evening. While left unrecorded, one wonders, did Luce or Linton’s involvement with the Lyceum have anything to do with Douglass’s invitation?

William Claflin was a Methodist, an ardent abolitionist and Governor of Massachusetts from 1869–1872 and a member of Congress from 1877–1881. Governor Claflin bought a cottage from the Oak Bluffs Land and Wharf Company in 1871 and supported both Indian and female enfranchisement. He and his father contributed funds to buy land for Claflin University, the historically black college in South Carolina that, founded in 1869, was named after his father.

Gilbert Haven of 10 Clinton avenue in the campground was an “unflinching” anti-segregationist who, in 1873, rode a Mississippi train coach reserved for ‘coloreds’ among other protests. Haven was one of the most outspoken U.S. abolitionists of the late 1800s who argued not just for ending slavery, but for the full social integration of African Americans. In 1874, when President Ulysses S. Grant came to Oak Bluffs, he was the Bishop’s house guest and attended his sermon.

Abolitionists helped pave the way for the tolerance experienced on Martha’s Vineyard, and especially in Oak Bluffs, celebrated by its exhibit in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. These men, too, are a part of black history.

Skip Finley is a former Vineyard Gazette Oak Bluffs town columnist. This is excerpted from his forthcoming book, Historic Tales of Oak Bluffs, being published this summer.

Comments (9)

Comments

Comment policy »