WASHINGTON, D.C. — When visiting the Smithsonian Institution’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture, be prepared for the emotion. It begins when you first see the striking glass building sheathed in brown metalwork that sits the National Mall, in the shadow of the Washington Monument and within sight of the White House.

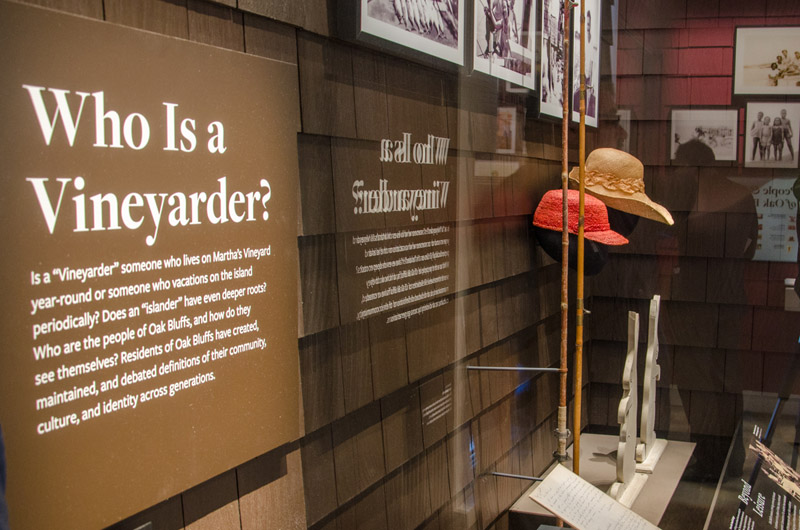

Expect it again when entering the third floor gallery called Power of Place, where the first thing you see is an exhibit that documents the story of the African American community in Oak Bluffs, now permanently on display for the millions of people who will visit the museum.

“To see it on display in the Smithsonian Museum, is really quite overwhelming,” said Lee Jackson Van Allen, owner of the historic Shearer Cottage in Oak Bluffs.

Ms. Van Allen, who donated several items for the Oak Bluffs exhibit, was among those who got an advance tour of the museum last week. “It brings such pride in who you are as an individual. It celebrates the contribution of African Americans over the years to our country, America. It is an American story.”

All told, the museum houses more than 37,000 artifacts of African American history.

A grand opening and dedication is set for Saturday, Sept. 24; President Obama will lead the ceremony.

The Oak Bluffs exhibit takes its place in a gallery with nine other communities that represent elements of American history, seen through the prism of the African American experience. The exhibits explore some of the places that became crucial components in the long struggle for equality.

Smithsonian historian Kevin Strait said while several communities were under consideration to represent the culture of leisure in the era of segregation, in the end Oak Bluffs stood out as the best example.

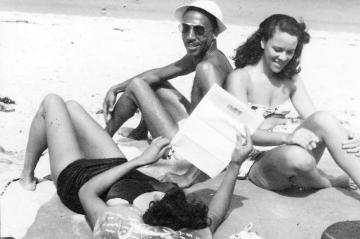

“We just started talking about Oak Bluffs,” he said. “It just seemed to make a lot of sense. We wanted to make sure that there was a space in this museum that reflected the joy of life when one goes on vacation. It’s not commonly reflected in these larger historical narratives. We wanted to have a space that reflected how African Americans over the years had built their own place and enjoyed themselves just like any other person would when going on vacation.”

Mr. Strait has more than a historian’s connection to Oak Bluffs; he and his extended family have vacationed on the Island for nearly 60 years.

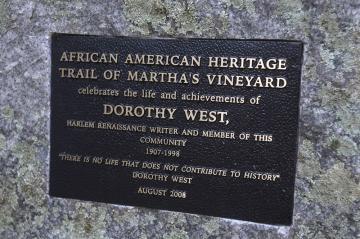

Curator Paul Cardullo said the nine years he spent planning and creating the Power of Place exhibits was the most exciting and thrilling experience of his career. He said the diverse, resonant stories of Martha’s Vineyard were the reason Oak Bluffs was chosen for a place in the museum.

“What that allowed us to do is combine the story of leisure, but also to really think about the complexity of leisure during segregation, the complexity of black middle class life during this era,” Mr. Cardullo said. “Not just what leisure means, but what sanctuary means, what safe space means, what having a place of one’s own means. There’s no better place, I think to discuss those kinds of questions than in Oak Bluffs.”

Artifacts and stories from the Shearer Cottage, founded and operated by Charles and Henrietta Shearer, are among those on display. Mr. Shearer was born into slavery, the son of a slave master and one of his slaves. Shearer Cottage, which opened in 1912, welcomed African American families vacationing on Martha’s Vineyard who were unwelcome at segregated hotels and inns of the era.

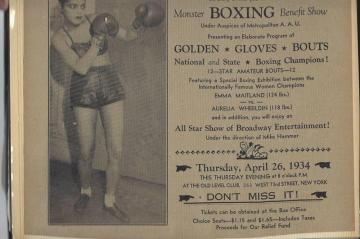

Wicker chairs that once sat on the front porch of the cottage are situated around a low table, along with programs from the summer theatre organized by Shearer family descendents to entertain guests. Also on display is a guest register which includes the signatures of Paul Robeson, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., and Harry T. Burleigh, who all checked into the guest house.

Mr. Powell, a civil rights leader who represented the New York city community of Harlem in Congress, loved the Island so much that he and his wife Isabel bought a home around the corner from the Shearer Cottage. Artifacts from their home, known as the Bunny Cottage for its decorative woodwork, are also on display. There are fishing rods, summer straw hats and historic pictures of the congressman and his family.

The walls are full of other historic photos and printed text. A continuous video display features Oak Bluffs residents and summer visitors talking about past and present life in the seaside town.

Accents of Island architecture are incorporated into the display, and a park bench facing the exhibit invites museum visitors to sit down and relax.

“You would be hard pressed to have an exhibit space on Oak Bluffs and not have it be comfortable, have it be cozy, to reflect the warmth of the area,” Mr. Strait said. “That’s why people go there. That’s why people enjoy themselves. That’s why people keep coming back to Oak Bluffs.”

While the museum has the grand feel of the Smithsonian, with historic artifacts that celebrate the soaring moments in African American history, it also spares none of the tortuous history of slavery, segregation and the civil rights movement.

On a lower floor is the casket in which 14-year-old Emmett Till was buried in 1955, representing a seminal moment when his mother chose to have an open casket at his funeral, so the world could see he was beaten and mutilated by relatives of a white woman he spoke to.

There are glass shards and a shotgun shell recovered outside the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., where four young girls were killed in a Ku Klux Klan bombing. Not far from the Oak Bluffs exhibit is a military display. The dress Army uniform of former Secretary of State Gen. Colin Powell, decorated with a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart, is next to a sign that once directed white officers to one officers club and black officers to another.

Also on display are Harriet Tubman’s hymnal, Nat Turner’s Bible, a World War II fighter airplane flown by the Tuskegee Airmen, a segregated railroad car, and an actual 19th century slave cabin from South Carolina.

On the top floor are bright and joyous displays illustrating the legacy of African Americans to the nation’s musical and literary history. Michael Jackson’s fedora is there, along with Louis Armstrong’s trumpet and Chuck Berry’s cherry red Cadillac. Music and poetry fill the exhibit through large speakers.

On Saturday, following the dedication and speech by President Obama, church bells will ring throughout the capital city, and around the nation, as they did in 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

The museum was created by an act of Congress in 2003 and signed into law by President George W. Bush, who will also attend the opening ceremony.

Efforts to build the museum of African American history date back more than a century.

“This museum is overdue,” said Mr. Cardullo. “We like to say it was 100 years in the making. It was promoted by black veterans of the civil war, celebrating the 50th anniversary of their service. That dream was held in abeyance for decades.”

Founding director Lonnie Bunch was among the museum officials who visited Oak Bluffs during the period when curators were collecting artifacts.

“If we’ve done our job right,” Mr. Bunch said recently, “I trust the museum will be a place for all Americans to ponder, reflect, learn, rejoice, collaborate, and ultimately draw sustenance and inspiration form the lessons of history to make America better.”

Learn more about the history of African Americans on Martha's Vineyard.

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »