The following is an edited and excerpted oral history interview with Doris Pope Jackson done by Linsey Lee. The complete interview appears in Ms. Lee's book More Vineyard Voices; it appears here with permission from the author, who heads the oral history center at the Martha's Vineyard Museum.

I was born in Everett. My parents were Lincoln G. Pope and Lilly Shearer Pope. They first met at Shearer Cottage, an inn located in Oak Bluffs that was owned by my grandparents on my mother’s side, Charles and Henriette Shearer.

My grandfather, Charles Shearer, was born into slavery. Henrietta Shearer was of Native American and African American descent. They were both educated at Hampton University. My grandfather graduated from Hampton. They both did, as a matter of fact. That’s where they met. She stayed on as a matron. And he stayed on for years there, at Hampton, teaching. They both also taught at schools in Lynchburg.

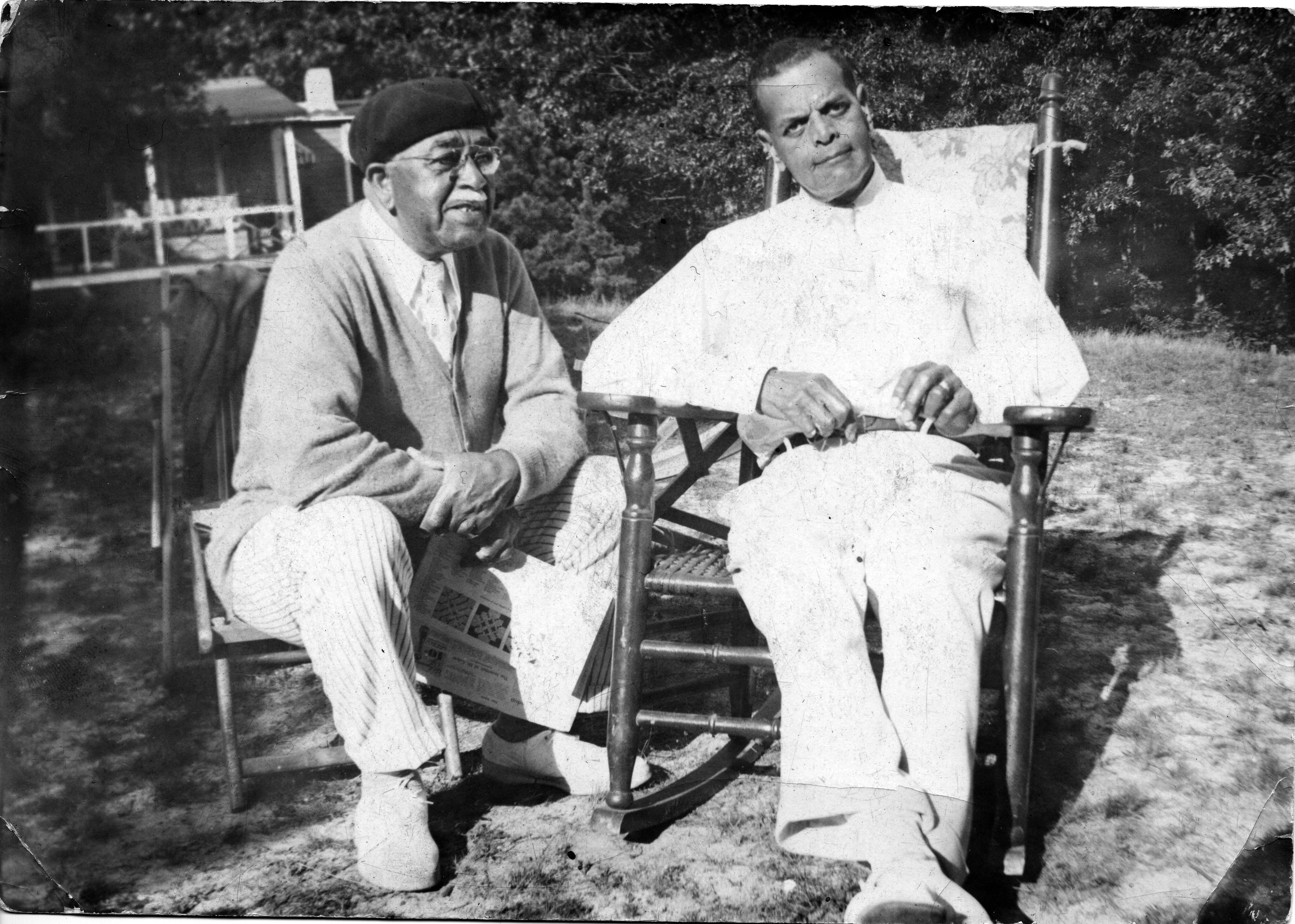

My grandfather’s story is interesting. During the Civil War he was a young boy. The Union soldiers came close to the plantation where my grandfather was a slave. The owner of the plantation, Master Shearer, was also my grandfather’s father. Master Shearer wanted to move further south with all his valuables. My grandfather had said that he wanted to join the Union soldiers, so Master Shearer chained him up in the barn and left the area, forgetting he was there. The Union soldiers found my grandfather in the barn and I understood that he traveled with the soldiers. He showed them different places where they could fish and hunt. Then, as I said, my grandfather went to school in Virginia and taught at Hampton. In the late 1800s, my grandfather moved his young family north to Everett, Massachusetts, where he purchased a home. He worked as a headwaiter at two of Boston’s fine hotels — the Young’s Hotel and the Parker House. As he was black he couldn’t get a job as a teacher, but at that time headwaiters were making more money than most people.

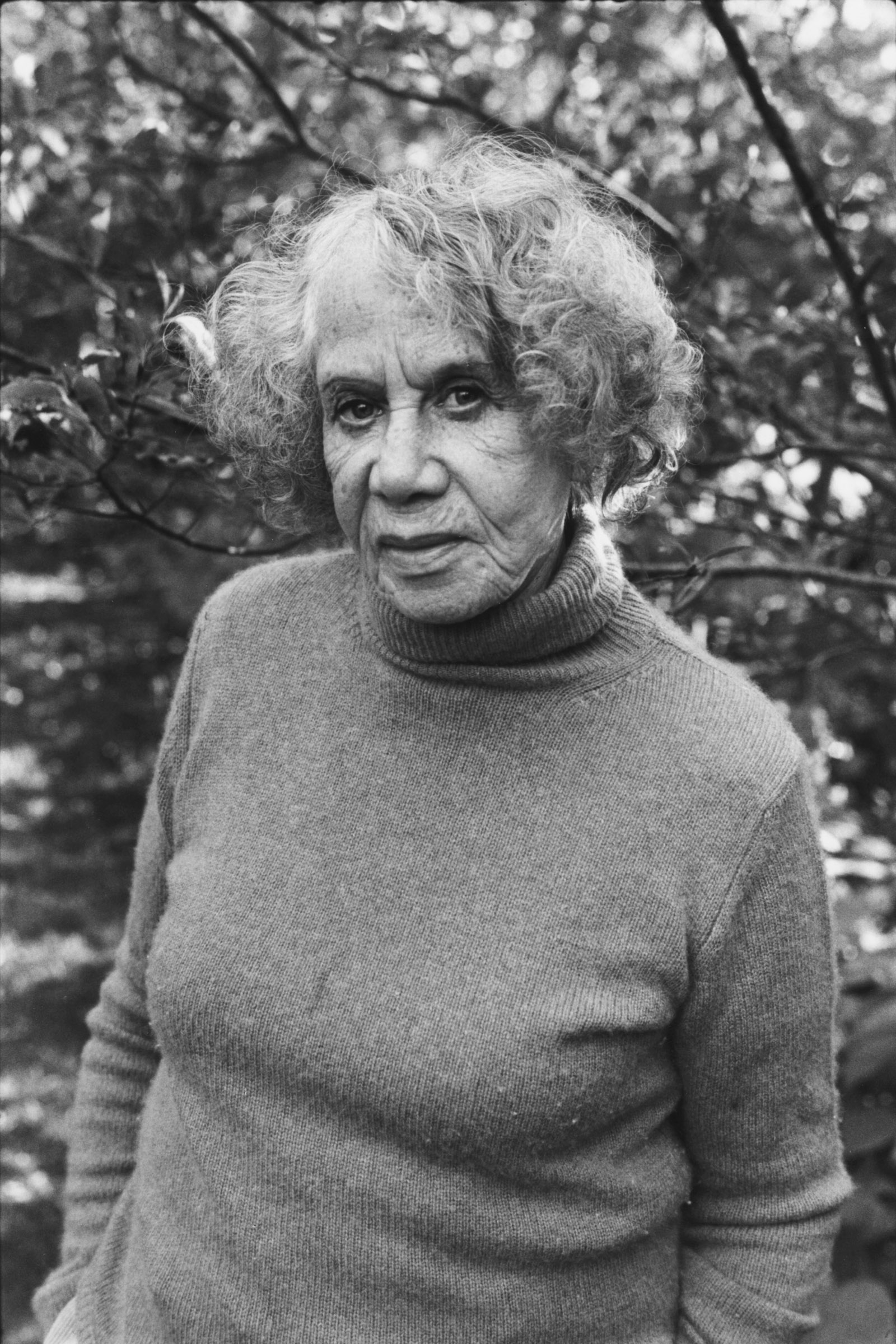

My grandmother died when I was very young. My grandfather died in the late 1930s, so I knew him well. Tall and straight and handsome. We spent a lot of time with him. He was articulate — you’d always see him in a starched shirt and tie and a Panama hat, always very proud. He was about six feet two. He was like a prince and he looked like one.

My grandfather Shearer first came to the Island to go to religious meetings at the Baptist Tabernacle here in the Highlands. In the late 1800s they bought property in Oak Bluffs. Then in 1903 they bought their home overlooking the Baptist Temple Park, where he would come to revivals. This is where Shearer Cottage is now located.

My grandmother Henrietta was very smart. She was a business woman. She built a “long house” on the side of their cottage and hired six Island women to work for her, and set up a laundry on the property.

When my grandparents acquired the property, their friends started to come to visit. But friends who came up to visit found it difficult to acquire rooming on this Island, because the hotels were not open to blacks. And that’s why my grandparents started Shearer Cottages, as a lodging house catering to African Americans.

Charles and Henrietta’s two daughters were my mother and my aunt — Lily and Sadie. They would come up every summer to help at Shearer Cottage. The whole family lived at Shearer Cottage. The family all cooked and helped and cleaned and did everything to hold on. And that’s what I do now. Because of the history of the cottage, I still work hard to hold onto my grandparents’ legacy.

Fortunately as children we had the benefit of knowing and loving this beautiful Island, and we’ve been here all our lives, in the summers. We always stayed up at Shearer on the top floor with my grandfather.

My Aunt Sadie was a marvelous cook. I remember my Uncle Robert; he was a chef and a wonderful one. Shearer Cottage was famous for its food. People still mention the food up there. The meals were fabulous. They were known for huge turkeys and huge legs of lambs, and everything delicious and Southern pies — blueberry pies, sweet potato pies. You know, Southern cooking. Full course breakfasts. Full course everything. That’s the way people ate then. But wonderful cooking, first class it was. Three meals a day.

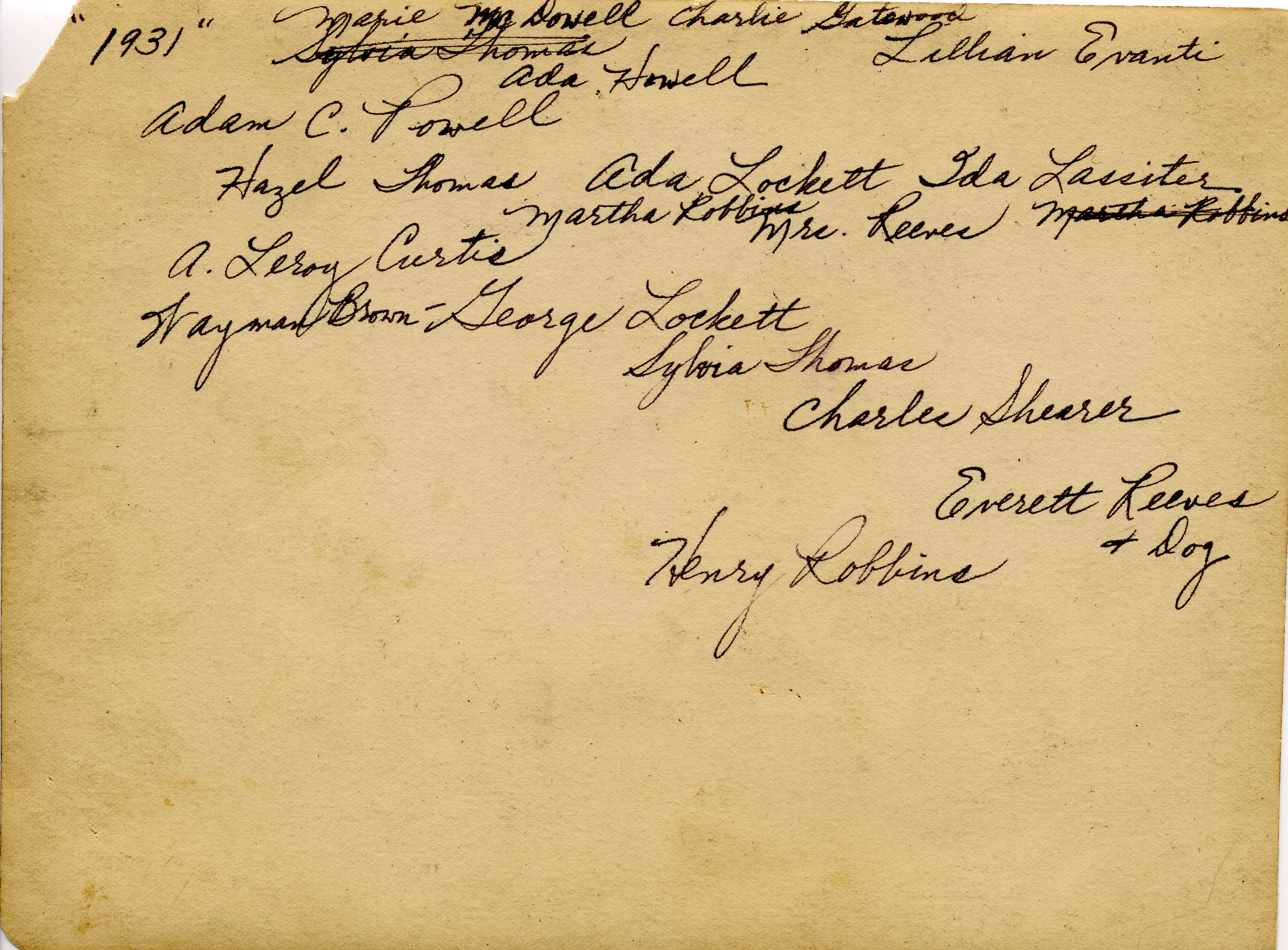

The guests were very prosperous people. All of these blacks were very well educated. Artists, judges, lawyers, principals of schools, teachers, congressmen, they all stayed up at Shearer Cottage. So it was packed up there. At times there were as many as 60 people in the dining room, because my mother and aunt used to rent several houses around Shearer Cottage, so that they could house everyone. Everyone would dress up for dinner. Beautifully dressed and well educated.

I remember Herbie Tucker, who’s now Judge Tucker. He and his sister used to come to Shearer for dinner. The Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Sr., and his son, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., who became the United States congressman, came. Dr. Fuller, a renowned physician from Boston, recognized as the first black psychiatrist in America — his family stayed there. He was married to the sculptress Meta Warrick Fuller. I grew up with his children; they stayed at Shearer Cottages years ago. And Ethel Waters and Paul Robeson, both famous actors and singers. And of course I remember Harry T. Burleigh. He was a marvelous person. He put many of the black spirituals to paper and preserved them. And he composed also. As kids, he’d always take us out for ice cream and candy. He spoiled all of us, Harry T. Burleigh. William H. Lewis, the first black assistant U.S. attorney general, was also a guest. In recent years, my cousin, Ben Ashburn, who managed Lionel Richie and the Commodores, brought them to Shearer and they played all over the Island.

As teenagers, we always worked up there. We waited on tables and cleaned the rooms. We were trained to work when we were kids. We enjoyed it. We were paid for our work and loved to spend our money downtown in Oak Bluffs. We didn’t work when we were really young. We were too busy getting to the beach and the Flying Horses. We might have been 15 or 16 when we started working at Shearer Cottage.

When we were teenagers we goofed off plenty, believe me. And we weren’t the best workers in the world, but everyone liked us, I mean, as waitresses and chambermaids. We got there at dinner time and were able to serve the guests. And we all grew up with them. Half of them we called aunt and uncle. So it was like a big family. They all knew us. Not that we got that many tips, but then you didn’t, I suppose. But someone in the family always worked up there. That was just the way, in order to hold on. We had no idea of ever selling that place. Our grandparents worked too hard. And I think that’s a good thing for most families to remember, that in my grandparents’ day, people who owned summer homes worked very hard to accomplish this. And my grandchildren appreciate this. That’s why they’ve all helped up there. Eventually they may buy their own homes here. But I’m sure they’ll hold on to Shearer.

Everyone says that Shearer Cottage has a special feeling. Why do other people feel Shearer is special? You’d expect me to feel that way. Often guests come and they have been having a difficult time, but when they leave they say, “I feel so wonderful now.”

Comments

Comment policy »