The Vineyard Gazette marks another milestone on Saturday: 170 years in continuous publication.

On May 14, 1846, Edgar Marchant introduced the Island’s first newspaper, announcing its mission across the broadsheet’s masthead to be “neutral in politics . . . devoted to general news, literature, morality, agriculture and amusement.”

It was the Golden Age of whaling, and early issues of the Gazette were filled with shipping news, the market for sperm oil in New Bedford and advertisements for sail repair, marine insurance and nautical instruments, along with groceries and dry goods.

On Tuesday, the newspaper celebrated the occasion with an evening hosted by writer Tom Dunlop, the Gazette’s unofficial historian, who described the challenges of producing a paper at a time when every letter had to be set by hand, in reverse. Here is his profile of Mr. Marchant.

He must have been at times impossible to deal with — a whirlwind of energies, an interrupter of other’s thoughts, a zealot about town affairs, the type that villagers probably ducked into shops to avoid if they saw him coming and didn’t have time to deal with him.

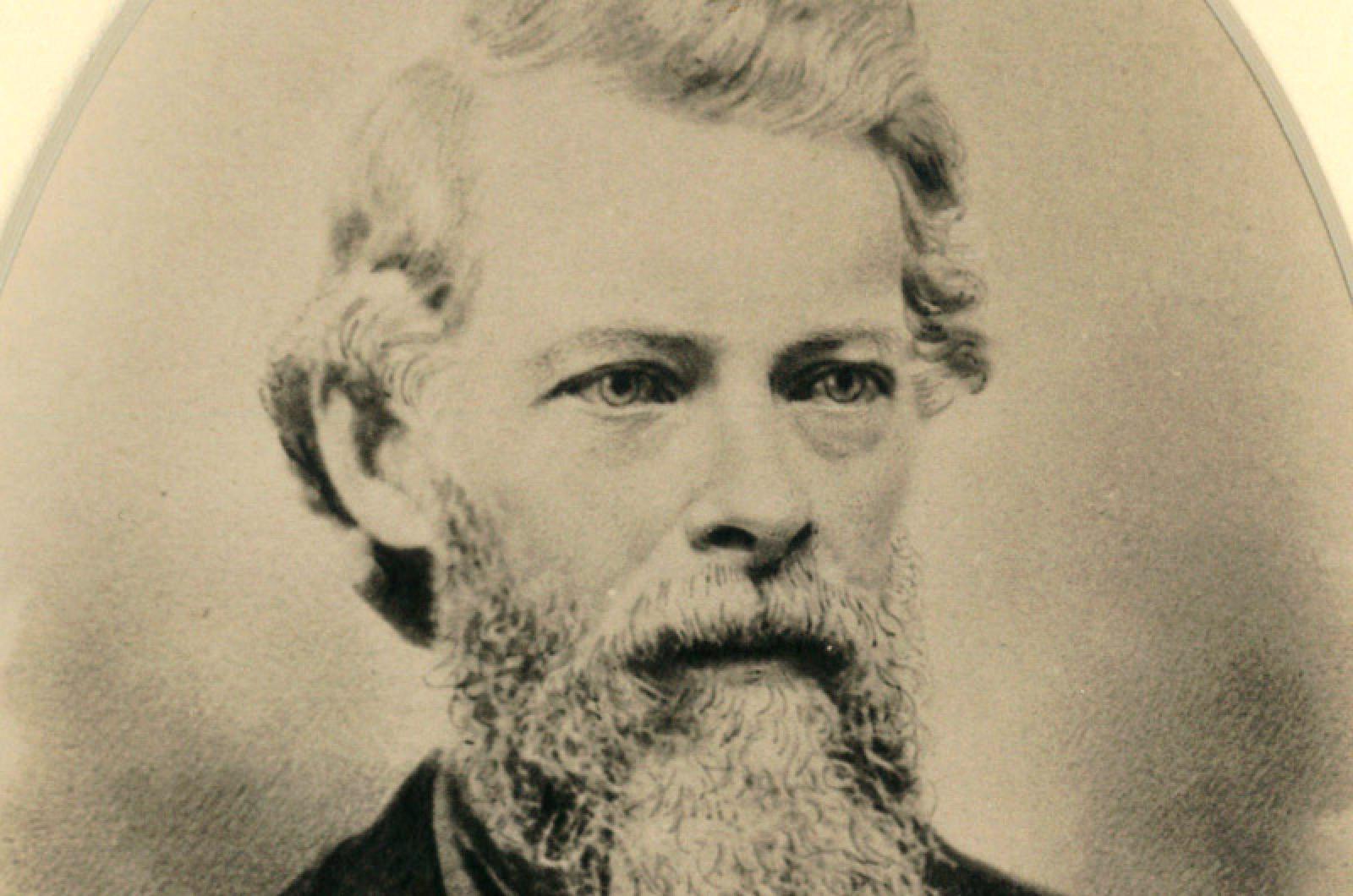

Edgar Marchant was the founding editor and publisher of the Vineyard Gazette. “[A] slight, nervous figure with deep-set eyes, mustache, full beard and wavy hair,” wrote Henry Beetle Hough, who edited and published the newspaper two generations later. “By choice he wore a cape over his shoulders instead of a coat, and he would stride along with the folds of that garment billowing in the wind.”

His temperament could be impatient and sarcastic. “A man of positive conviction, he waited not first to learn what others thought, before uttering his own opinions,” wrote the town official and historian Richard L. Pease after Marchant’s death in 1878.

But looking back now, Marchant’s ideas about where the Island ought to be going in its civic and economic life were visionary. And probably no one had more influence on the life of Martha’s Vineyard across the entire span of the 19th century. With his first edition of the Gazette — published Thursday, May 14, 1846, 170 years ago this week — he became the sole person empowered to tell the whole Island what was really newsworthy about Vineyard life that week. And he had the added power to set an agenda for political and economic debate.

He was born on May 2, 1814, on the site of what is now the Edgartown National Bank, the son of Captain George and Abigail Butler Marchant. The eighth of 12 children, he learned the printer’s trade on the mainland and returned home to establish a paper that would reliably offer news of the Vineyard but also, as reports or newspapers came in by packet boat and merchant schooner, the continent and the world beyond. Before the Gazette, there was no other regular source of mainland news to be found on the Island.

Politics, business theory, rallying cries, criticism, history and insight were all unspooled by Marchant for a Vineyard audience in real time. And if you had ideas of your own and wanted them to reach Edgartown, Tisbury or Chilmark (West Tisbury, Oak Bluffs and Aquinnah did not yet exist as townships), you wrote a letter or sent an essay to Marchant of the Gazette. He was the gatekeeper to the rest of Martha’s Vineyard as well as a booster or opponent of what you had to say.

He was a Democrat on an Island of Whigs and later Republicans, a moralist appalled by the effects of drink and moral backsliding on the villagers of his town. And he was forward-looking, a true seer.

“Improvement seems to be the order of the day,” he wrote in October 1846. “In all human probability, judging from the present indomitable enterprise of our citizens, the years will be comparatively but few, before the abrupt steps of the Rocky mountains will afford no impassable barrier. . . . But touching on the matter of speed in the means of transit, who can tell what powers will yet be employed to accelerate that of the railroad car? Or how fast we shall go when we run, or rather fly in air-cars? Or perhaps be shot through the airy heavens from Boston to New Orleans by the power of electricity?”

Most of all, Marchant was an ardent booster of Island commerce. He saw that the economic fate of the Island rested on a single industry: whaling, in its golden years but showing early signs of uncertainty the year he started the Gazette. On paper, he was the first man to call for the Island to establish itself as a “watering place” in the summer season, a resort that would serve a small but adventuresome and growing middle class that would appreciate its rough, isolated beauty and simple, honest way of life.

“We don’t want the blacklegs of Newport,” he wrote in 1858, “or those of that character who visit that place in summer; neither do we wish to furnish drinking and smoking saloons to rowdy customers; and certainly we don’t want the conceited fop and the pert miss, who have nor sense enough for any manly or truly feminine enjoyment; but we do desire to possess that class, of moderate means, or large incomes, who have taste enough to enjoy leisure, quiet, pleasant and improving social intercourse, and have a desire to respect the Sabbath and avoid all immoralities.”

Indolence, suspicion and selfishness in matters of public enterprise drove him crazy. He had dared to sink everything he owned into an offshore newspaper; he saw no reason why other Islanders couldn’t risk as much and work together to promote works that would benefit all. When Edgartown looked like it would balk at investing in a railroad that would run from Cottage City to Edgartown and out to a hotel on the blustery plains of Katama during a time of national depression in 1874, Marchant spoke out on the floor of town meeting:

“If we refuse to encourage and lend our aid to this enterprise, the town will soon disappear into darkness and oblivion. All spirit of improvement will depart from our borders, men of brains will go where they can use them, and for aught I can tell to the contrary, the town will become a waste, a howling wilderness. Rats and mud turtles will crowd our streets, and owls and bats sit in our high places.”

By this point in his career — Marchant was in his 19th year at the Gazette, having sold it in 1863 and reacquired it in 1872 — his influence had grown deep and wide. The resort he envisioned had indeed grown up on land that surrounded the Methodist camp meeting of what is now Oak Bluffs. His economic forecast had proved to be accurate; whaling had failed as a meaningful Island business after the Civil War.

The motion to invest the enormous sum of $15,000 in the railroad passed by a single vote.

And as his second term in the editor’s chair came to a close in the fall of 1877, it was clear that the Gazette had become an indispensable journal of Island life and a relentless advocate for the prosperity of everyone it served.

Edgar Marchant died in Boston of typhoid pneumonia on Jan. 13, 1878, three months after his retirement. On the day of his funeral, the church was filled, stores all across town were closed and flags were lowered to half mast. Islanders had lost an important public figure in their lives.

Perhaps this respect was rooted at least partly in the fact that for all his impatience and fiery opinions, Marchant had also opened the pages of the Gazette to those who disagreed with his views.

Answering a critic, he once wrote this about being the editor of a country newspaper:

“. . . . Ah! It is the life of lives. The confessions of an opium eater would be nothing to his confessions. He is a man of all work, a miscellaneous personage, all the way up from a [printer’s] devil to a gentleman. He knows, or should know, everybody and a little of everything. He is in the world and out of the world, and lives in the past, the present and the future. He must sometimes see and not seem to see — sometimes hear and not seem to hear. He must examine this communication and refuse that, a duty anything but pleasing or consoling. He must read melting stanzas and white oak rhymes . . . . Indeed, an editor must be all things to all men, or all men will be nothing to him.”

Comments (4)

Comments

Comment policy »