Just over 100 years ago, on May 27, 1920, the Vineyard Gazette published volume 75, edition number 14. The entirely unremarkable issue looked and felt much as the more than 3,500 previous print editions that had appeared for 75 years. Advertising for things such as New Bedford silks, government bonds and mail-order vegetables dominated the front page, flanked by a slender boilerplate treatise on wolf hunting, and a story chronicling the exploits of an expedition to the “never hitherto penetrated” Arctic isle of Baffin Land.

The world — and Island — were just emerging from a devastating pandemic that had taken the lives of millions of people, including more than 20 on Martha’s Vineyard.

Still, as was true of most other community newspapers across the country, stories on the front page that day had absolutely nothing to do with the place its readers called home, in this case a subarctic isle 1,000 miles south of Baffin.

But the world was changing fast — and so was the possibility for intrepid, original and hyper-focused local news in community newspapers around the country.

On the Vineyard, the change happened nearly overnight.

Two weeks after the May 27, 1920, edition a young, enterprising mainland couple that had graduated together from Columbia Journalism School took ownership of the Gazette. They tore up the front page. It would never look the same.

The Vineyard Gazette celebrates its 175th anniversary Friday at another time of extraordinary change, with community newspapers across America dying at unprecedented rates.

“This is an astonishingly significant moment in the history of the Gazette as a publication,” said Bow Van Riper, a research librarian at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum. “And not just because of the anniversary year ending in five.”

Gutted by the advent of social media, the decline of print advertising, the digitization of classified ads and competition from big tech players like Google and Facebook, thousands of local newspapers have disappeared in the past 20 years alone, gobbled up by larger news outlets, or left to fade into obscurity with other, once-ubiquitous civic institutions of American main streets.

Many newspapers that have survived have done so by outsourcing layout and printing, transitioning to color and putting up paywalls on websites. The rest have simply ceased to print altogether.

When the Gazette celebrated its 150th anniversary in 1996, the landscape for print media was already on a downturn from the boom times of the 1980s. Two decades into the 21st century, there is hardly a landscape at all.

Yet the Gazette, which remains a black-and-white weekly broadsheet printed on a Goss Community Press in the back shop of its 18th-century office on South Summer street in Edgartown, thunders on as a modern relic of a bygone era. For 175 years, it has never missed a week in print, effectively serving as the heartbeat of an Island community.

How that heart has continued to pound — rumbling on week after week like the four-bay press that churns out the paper — is no mystery to the hundreds of staff who have poured their hearts into its production.

But it is a remarkable story, made of equal parts radical willingness to change and a radical commitment to staying the same. Happily, it remains a story without an ending.

Founded in 1846 at the peak of the whaling era by a 32-year-old mainland newspaperman named Edgar Marchant, the Gazette spent its first 75 years focused largely on the world beyond the triangular Island seven miles off the coast of Cape Cod.

Known as a high-strung, nervous man, Mr. Marchant had a simple editorial vision, according to Edgartown historian Tom Dunlop: concentrate on the news of the world, of which Islanders likely knew little, and steer clear of the news of the Vineyard, of which Islanders probably knew far more than he did.

That’s largely what Mr. Marchant and his immediate successors did, meticulously reporting ship logs and cramming the paper with medicinal patent ads for everything from sarsaparilla root to snake oil halitosis cures. The earliest editions included tales of the harrowing conquest of Vera Cruz in the Mexican-American War, a cholera outbreak in Boston and a recent tariff bill in Congress — all told in gray walls of text that could be found in comparable newspapers across the region.

“That part of the Gazette would have been very mainstream in the 1840s,” said Chris Daly, a journalism historian and professor at Boston University who is a seasonal Aquinnah resident. “As far as content goes, newspapers in the 1840s were a mishmash of a million things. Letters, poetry, jokes, even stolen fiction . . . they were much smaller, and it was a challenge to find content.”

Mr. Marchant relegated local news to the second page, focused more on editorializing than reporting, campaigning for railroads, temperance, industry and — in one of his first editorials — the prospect of the Vineyard as a summer “watering hole,” a development he and his successors vigorously supported.

“Early in his editorship, Marchant says, this place could be a resort,” Mr. Dunlop said. “And that’s a thread that continued for much of the next century.”

The makeup of the papers was based partly on logistics, and partly on economics. It took hours — if not days — to set type on the old Adams press, making boilerplate an efficient choice. News traveled slowly, and so did newspapers, with the Gazette not just the only source of Island news, but often the only source of news for Islanders. And Mr. Marchant had neither the time, nor the horse, to gather news. It had to come galloping to him.

So when the 1,008-piece Fresnel lens arrived from Le Havre for the Gay Head Light in 1856 — after being ordered by an act of the U.S. Congress and subsequently lost in the mail — Mr. Marchant treated it as he did most any other unexceptional small town Island affair: with no mention at all.

Gay Head, from the perspective of early Gazette editors, was farther from Edgartown than the Arctic.

“If you look at a 19th century Gazette, the thing I always find striking is how amazingly little local news there is,” said Mr. Van Riper. “And there is almost nothing that a modern-day newspaperman would call local reporting.”

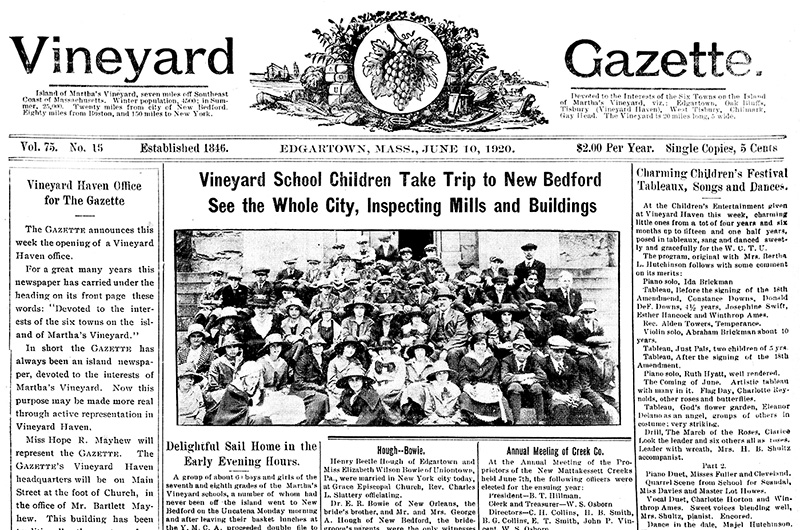

On June 10, 1920, the Gazette published volume 75, edition number 15. It might as well have been a different paper.

A bold five-column photograph on the front page accompanied an original reported story that was headlined: “Vineyard School Children Take Trip to New Bedford, See Whole City, Inspecting Mills and Buildings.”

There was other local news too, and an announcement that the Gazette would be opening a Vineyard Haven office, a significant shift for a newspaper that had almost exclusively focused on Edgartown for 75 years.

“In short, the Gazette has always been an Island newspaper, devoted to the interests of Martha’s Vineyard,” the announcement read. “Now this purpose may be made more real.”

But perhaps most important, the paper carried a prominent marriage announcement for Elizabeth Bowie and Henry Beetle Hough. They were due to immediately take up residence in Edgartown.

Henry Hough and his bride had received the Vineyard Gazette as a wedding gift from Mr. Hough’s father. In a few short weeks, they had completely overhauled the Gazette’s front page. Perhaps unknowingly, they had overhauled community journalism too.

“It’s an interesting coincidence that this is both the 175th anniversary of the Gazette, but also a century since the Houghs took over,” Mr. Van Riper said. “You dip into any point in the preceding 75 years and the Gazette looks visibly different from 1920 or anything again . . . It’s like a curtain has been drawn back all of a sudden, and somebody looking from that first Hough issue to the issue that came out last Friday, would see an enormous amount of visual and design stability.”

While some of the changes the Houghs introduced in that first edition were already coming into place by the early 20th century, with less national advertising and more original news, the Houghs accelerated the pace, matching stories with photography and purchasing a second-hand Whitlock press that could print 1,000 copies per hour. By 1929, they had bought a Duplex press, capable of printing 3,000 copies per hour.

Even more important, they bought a linotype machine for the steep price of $3,500. The genius of the machine was that it could make a whole line of type in one piece — called a slug — removing hours from the exhausting labor of hand type-setting. It freed the Houghs to focus on gathering and writing news — from Edgartown to Vineyard Haven and beyond.

“Under the Houghs, the Gazette . . . sets out to not just report the bare facts of this meeting, that meeting, another meeting, but sets out to capture the rhythms and feels of life on the Island,” Mr. Van Riper said. “Which, on the one hand, gives it that intense locality, that intense feeling of being part of a small town. But also all the warm fuzzy stuff that people say about the Gazette when people ask about it.”

Just as the world globalized, with cars and telephones becoming commonplace, the Gazette localized, yoking its survival to the survival of the community it covered.

The newspaper expanded to eight, then 10, and then 12 pages. In 1929, the Gazette began publishing twice weekly from June to September, creating a summer Tuesday edition that would continue until 2013.

Mr. Hough wrote editorials and eloquent nature essays, while Mrs. Hough, a straightforward newswoman, scraped together weekly editions detailing children’s choirs, church socials and club meetings — bringing the Island to the readers and Martha’s Vineyard to America.

That was exactly the point. Mr. Hough — who would later crusade against McDonald’s and cement his reputation as an ardent conservationist — at first snatched the baton straight from Mr. Marchant, campaigning relentlessly in the early days for the Vineyard to become a summer resort.

“If you look at the Gazette in the 30s and 40s, [Hough] is an absolutely ferocious booster of tourism and coming to the Island,” Mr. Van Riper said. “And you read Marchant’s editorials, and he’s looking up the coast of Oak Bluffs, saying, go boys go.”

By the 1930s, the newspaper’s gray wall of text had largely disappeared, replaced by unique weekly issues and special editions. The first Invitation Edition came out on April 14, 1933, with a banner headline that read “Martha’s Vineyard Has Many Delights for All Vacationers,” and a list of “Fifty things to do, places to go, things to see on this unspoiled Island removed from the mainland.” The first Directory Edition came out in June that year, complete with a map of the Island and a history of its scenic North, South and Middle Roads.

If people weren’t already coming, Mr. Hough made sure they at least knew what they were missing.

Thirty years later the Vineyard was changing — and so was the Gazette.

The world had begun to heed the call to come. In the newspaper’s first century, survival had meant championing the Vineyard as a summer resort. But as the Island shifted, the newspaper began to campaign relentlessly to preserve the sense of place and people that made the Vineyard unique.

Betty Hough died in 1965, and Mr. Hough, the legendary country editor, had begun to worry about the future of his paper.

In 1968 he sold the Gazette to James (Scotty) Reston, the famed New York Times columnist, and his wife Sally Fulton Reston. Mr. Hough retained his role as editor, but eventually would turn the reins fully over to the Reston family.

In 1975 Richard Reston and his wife Mary Jo Reston took the helm, first on the business side, eventually becoming publishers, with Mr. Reston the editor and Mrs. Reston the general manager. Together they ushered in yet another new era for the old broadsheet, including the change to photo offset printing on the four-bay Goss Community press still used today.

“When I got there, the circulation was around 5,000 . . . we were barely breaking even,” Mr. Reston recalled in a phone interview. “And then we went from a kind of sleepy time, to all of a sudden a time of real explosion of development, and a thirst to build, and to build at will. And therefore, very quickly, our fight was, could we preserve the Vineyard, and the character of the Vineyard, through responsible planning? That became the battle. And it ranged from keeping McDonald’s out to saving South Beach.”

Just as the Vineyard’s weight class expanded, so did the Gazette’s, readying it for the preservation battles of the 1980s and 1990s. Advertising was stacked high on print pages. The paper had an entire section for classifieds, representing a boom time for an industry that had never really known one. And as the Gazette campaigned against unbridled development, a group of local businessmen who were unhappy with the paper’s editorial policies, founded the Martha’s Vineyard Times — the latest in a 14-paper line of Gazette competitors.

Meanwhile, the Restons had solidified the Gazette as a teaching paper, recruiting dozens of young reporters from places like the Harvard Crimson and fostering a new generation of writers, artists and photographers. They rarely made deadline. But they always made a paper.

“It was a labor of love for all of us,” said Alison Shaw, longtime photographer and former director of graphics and design at the Gazette, recalling the many all-nighters on South Summer street putting out huge editions. “I remember mornings, going to the Dock Street Coffee Shop . . . . to get my coffee . . . . to keep working,” she said.

When Hurricane Bob hit in 1991, the Restons refused to let the power failure that blanketed nearly the entire Island stop the press run for the first time in 146 years. A makeshift news bureau was set up in the Vineyard Haven advertising office. A skeleton production crew flew to Nantucket, where there was electricity and a working press at the Inquirer and Mirror. It was a logistical nightmare that even Mr. Reston could only remember in parts. “I don’t scare very easily, but there were certain moments of fear,” he said. “I simply felt that some other publisher or editor could break the record, but by god it wasn’t going to be me.”

The paper was printed. It was runner-up for a Pulitzer Prize.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, economic pressures provided existential challenges for the still old-world Gazette. As other small papers drastically shrank print editions and lost their pressrooms, an internal debate roared over whether to switch the Gazette to color printing. Among other things, it would have meant shifting production off-Island.

In an internal position paper, Mary Jo Reston argued strongly against the move.

“The paper is a throwback to another time, carefully designed and literate . . . I fear that if we change the size of the paper, move to color and short bites of information, we’ll lose any audience we have,” she wrote. “A change would make us like most other newspapers, homogenized news and certainly not special. Our present uniqueness is also like the Vineyard.”

As the century turned, the Gazette made a decision essentially by not making one, becoming a one-of-a-kind publication as its peers faded away. The newspaper’s old-fashioned, seven-column format is unique.

“The Gazette print edition may be the most beautiful newspaper in America,” Mr. Daly said. “It is just extraordinarily good looking. And so many of the surviving, local newspapers are really ugly.”

But there was no guarantee either that the Gazette would survive. The pressures of the digital age squeezed what little was left of the paper’s profit margins. By 2008, the paper was quietly on the market and it appeared possible that the Gazette, too, could disappear — despite the efforts to retain what its readers held dear.

In 2010, philanthropists and longtime Island summer residents Jerome and Nancy Kohlberg acquired the paper in a historic deal, donating the Gazette building to the Vineyard Trust to ensure the paper’s home in perpetuity.

In a break with tradition, the Kolhbergs sought an experienced publisher to run the business and hired Jane Seagrave, an executive with The Associated Press.

“The Kohlbergs loved the paper, loved its traditional format, but understood it needed to evolve and had no desire to operate it themselves,” said Ms. Seagrave. “I always try to keep in mind what Mr. Kohlberg said at the time he bought the paper, that he wanted it to continue to be a vibrant voice for the community.”

But the paper also needed to operate as a business. Part of the focus in the last 10 years has been on adding new publications and revenue sources, as well as overhauling its website, adding newsletters and sponsoring events.

Jerry Kohlberg died at age 90 in 2015. He is survived by his wife, four children, and the paper he couldn’t let go.

As the Gazette celebrates its 175th anniversary, dozens of large newspapers across the country are following the precedent set by the Kohlbergs. The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times and Baltimore Sun have all been purchased by wealthy philanthropists with the goal of preserving the papers as bedrocks of democracy, rather than letting them fall into the hands of hedge funds or venture capitalists.

None are as old as the Gazette, which was founded eight days before Ms. Seagrave’s former employer, the AP.

“We’re older than the Smithsonian,” Ms. Shaw said. “We’re carrying 175 years of tradition. And it’s not just the paper. It’s what it stood up for.”

The Gazette has had its share of failings. For more than a century, its coverage of race was not just imperfect, but often non-existent. The dark history of Wampanoag colonization was noted only with a passing mention, and segregation on the Island was hardly ever mentioned. Often the paper appeared overly focused on the Vineyard summer community, overlooking the issues that occupied year-round, working class Islanders. It has missed stories, made thousands of errors, even shunned the Oxford comma — one feature of a quirky style guide created by Mr. Hough that confuses some readers, confounds young reporters and has been difficult to maintain.

Despite its missteps, the Gazette has soldiered on.

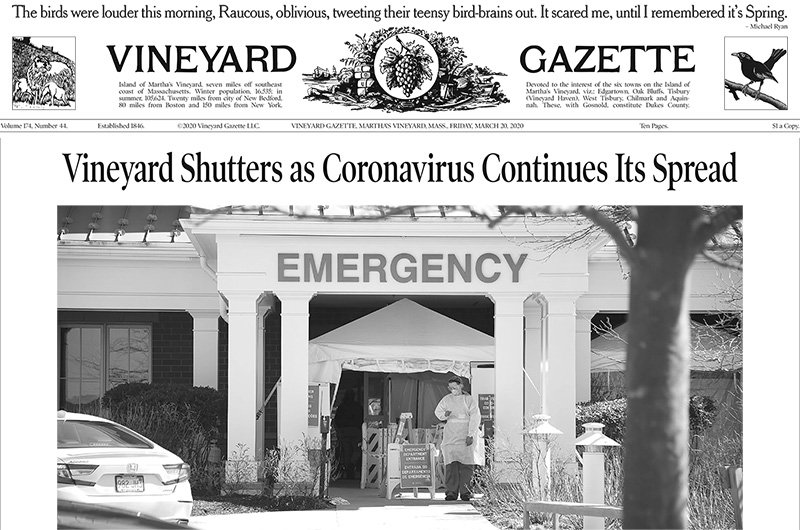

Last March, when the pandemic hit almost exactly a century after the Houghs took ownership of the paper, the Gazette quickly reshaped itself online and in print, carrying news and information more vital than ever for the community.

During those early pandemic days, the newspaper also made a commitment to continue printing, despite fears of a virus that remained unknown to the world.

Pandemics had happened before. But the Gazette had never covered them on its front page. So the editorial staff did what the Houghs did: they tore up the old layout and made a new one.

“We were in an emergency and the paper needed to reflect that. But we also wanted to convey the message: steady at the helm here,” editor Julia Wells said.

Of course, the seven-column black-and-white broadsheet, the line of poetry across the top of the front, and the bird news on the last page, all remained.

Some things are worth preserving.

Vineyard businesses offer their congratulations to the Gazette.

State Legislature issues proclamation congratulating the Gazette.

Comments (8)

Comments

Comment policy »